Minerals like graphite (and graphene) may be rewriting our energy future. Image: “Electromagnetic induction” animation by Ponor, 2005. Creative Commons 4.0.

Graphite may be one of the answers to the carbon transition. Carbon in its purest crystalline form, graphite is rewriting energy, especially in its related form of graphene. Graphite is basically thousands of layers of graphene. What are these two and why are they named after writing?

If you have ever taken a test or made notes with a pencil, chances are it is No. 2 “lead”. In fact, it is not lead (as was originally thought, hence the name) but made with graphite. Because graphite comes in a variety of options: H markings designate its hardness (2 or even 3 for a harder core) or B for blackness of resultant writing.

Graphite is commonly used in pencils. Some say the pencil was an early enabler of widespread education. Image: “HB pencils” by photographer Dmgerman, 2007. Creative Commons 3.0.

What is graphite and why it is called by that name? Around 1550, in Borrowdale, Cumbria, England, sheep farmers who discovered a large deposit of the mineral found it very effective for marking sheep, identifying those in their herds and flocks.

Graphite was originally used in Borrowdale, England, to write on lambs and sheep. Image: “Sheep, Stodmarsh, Kent, England” by photographer Keven Law, 2008. Creative Commons 2.0.

Writing on sheep soon expanded to centering this new material in casings of wood to be used as a writing instrument. We can credit Abraham Gottlob Werner for coining the term graphite (“writing stone”). Thus was born the pencil. It was so effective at writing, and so abundant in nature (along with wood to encase it), that some historians credit the invention of the pencil with the expansion of public education. No longer would a quill be needed.

Before graphite pencils, quills and ink were needed for writing. Image: “The Bookkeeper” by Philip van Dijk, circa 1725. From Gallery Prince Willem V, The Hague, Netherlands. Creative Commons0 1.0: public domain.

Graphite proved versatile. Resistant to heat, yet malleable, it came to be used in lining molds for cannonballs. It could be fashioned into a crucible, a container for mixing metals at high temperatures. Graphite became so important in England that it was controlled by the Crown.

Cannonballs may not be used in modern warfare, but persist in mythology. Here, Marvel Comics “Cannonball” from X-Men, 2007. Image: fair use. With appreciation to Marvel Comics.

Because graphite is resistant to heat, and also can conduct electricity, it entered a new era in the 1970s for use in batteries. Graphite is an excellent anode (the electrode of a polarized electrical device through which a positive current enters the device). Its partner, the cathode, is where current leaves the device. These words, too, were coined. In 1834, William Whewell and Michael Faraday discussed the need for a name. They decided upon the inspiration of nature, following the path of the sun. Anode was patterned on Greek for “ano = upwards” + “odos = the way” – it was a model of the sun rising. Cathode was from the Greek “kath = down” + “odos = the way.”

Anode and Cathode were named after the rising and setting of the sun. Image: “Sun Animation” by designer Sfls4309pks, 2018. Creative Commons 4.0.

Graphite is a dominant anode material in lithium-ion batteries. Manufacturers of batteries and related applications continue to develop innovations for graphite use. Graphite is so important in industry that more than 60,000 patent applications for graphite technologies were filed in the decade 2011 to 2021: China filed 47,000.

“Lithium cobaltate vs graphite lithium-ion battery schematic” by Sergey WereWolf, 2016. Donated by the graphic artist to the public domain, Creative Commons0 1.0. Included with appreciation.

Generally, graphite is mined. Most comes from China, India, Brazil, Turkey, and North Korea; it was also once mined in the United States. World reserves of graphite can be found in Turkey, China, Brazil, but also Madagascar, Mozambique, Sri Lanka and Tanzania. Purity varies: Sri Lanka has deposits with a purity of 99%. Ride a Sri Lankan graphite mine elevator here.

Graphite Mine in Kmegalle, Sri Lanka, circa 1897. Image from Cassell & Co. This image is in the public domain.

Graphite can also be synthesized: Edward G. Acheson was the first to do so Like many scientific discoveries, it happened by accident. But the patent Acheson received in 1896 opened a new industry for synthetic graphite.

Acheson Process for synthesizing graphite. Image: “Acheson furnace” by graphic artist Quasihuman. Creative Commons 3.0.

Graphite can be recycled, with the resultant powder used to amplify the carbon content of molten steel. Recovering graphite from batteries or lubricants (or the core of nuclear reactors) involves sulfuric acid curing, leaching, and calcination to separate reusable graphite. In current practice, recycling of the cathode part of batteries has been common, but less so the spent anode graphite. But with scarce new resource supply and environmental trends, regneration of spent graphite anodes from electric vehicle batteries will increase (Shang, et al., 2014). The global market for recycled graphite is still small: $45 million in 2021 projected to grow to $110 million by 2031 – maybe much more.

Graphite may be most valuable as the parent source of graphene, which is extracted from the mineral. Graphite is composed of layers with rings of carbon atoms that are spaced in horizontal sheets. Graphene is derived from Some herald graphene as the future of sustainable materials. It is used in applications as diverse as mobile phones and solar panels. It’s pure carbon and it is strong – more than 200 times stronger than steel. And it’s light – five times lighter than aluminum. It has thermal properties, it conducts electricity. In batteries, graphene could increase battery life by 10 times, shorten charging time. Because it is so light, yet powerful, graphene is ideal for batteries that power drones. Because it is heat resistant, graphene could lessen the danger of batteries overheating.

Graphene nanoribbon band structures. Graphic by Saumitra R. Mehrotra and Gerhard Klimeck, at www.nanoHUB.org. Creative Commons 3.0.

So, is graphene the same as graphite? No, but they are related. the International Union for Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) made the key differentiation. Graphite is three-dimensional. While scientists knew about it, graphene was difficult to isolate. In 2004, Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov succeeded at the University of Manchester. In 2010, they received the Nobel Prize in Physics. Their process involved pulling graphene layers from graphite. The Prize noted “groundbreaking experiments regarding the two-dimensional material graphene.” (Nobel Prize 2010) It should be noted that subsequent discussion revealed the omission of Philip Kim of Columbia University; Geim responded he would gladly have shared the Prize with Kim.

Identification of graphene from graphite merited the Nobel Prize in 2010. Image: “Nobel Medal” by photographer Klaviaturka, 2018. Creative Commons 4.0.

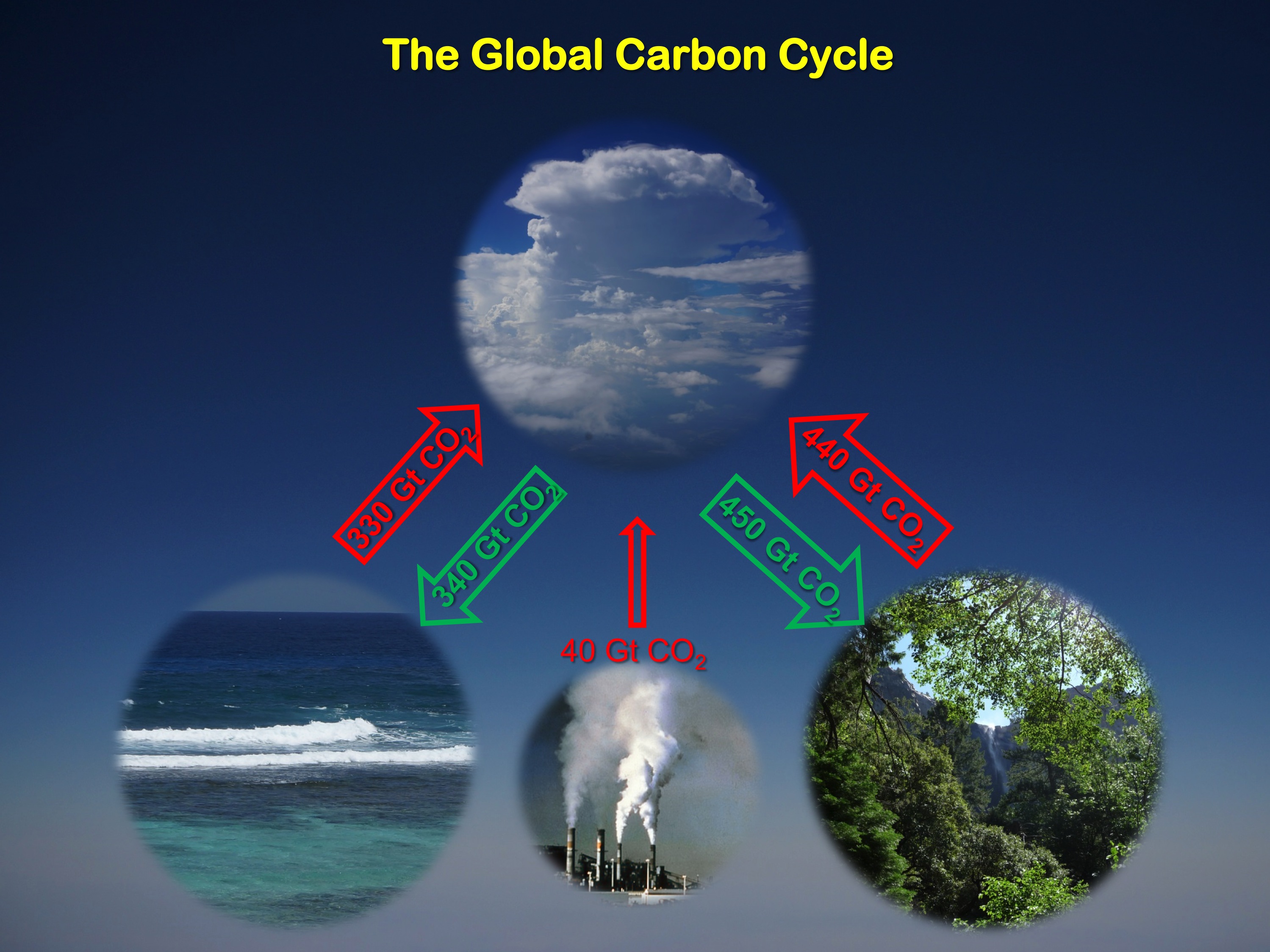

Graphite is the crystalline form of carbon. It comes in three forms: amorphous, flake, and vein. It can be found in coal and shale. Flake carbon has the highest carbon content : 85-98 percent. Vein carbon is rare. but pure carbon up to 99 percent (it is now mined in Sri Lanka). Back in the early days, graphite was burned but in 1779 it was found to emit carbon dioxide under combustion. So, is graphite part of the carbon problem? Perhaps. Graphite is the most stable form of carbon, but it can release carbon emissions during a process called spheroidisation during which carbon flakes are placed in a mechanical process that rounds the particles. It’s a process that improves anode performance, but some flakes are lost and produce emissions. Most carbon emissions associated with graphite, however, come from the carbon-based fossil fuels that power the processes of its manufacturing into products.

“Graphite” by photographer Alchemist hp, 2014. Creative Commons 3.0.

Because it is pure carbon, graphite can become coal, and could theoretically be used as a fuel. But it is so valuable in so many other applications, like batteries, that its future as a fuel is most unlikely and environmentally undesirable. But there is one other high value thing that graphite, under very high pressure and intense heat, could become – a diamond.

A diamond is carbon. Image: “Tacori 2620 Round Diamond” by TQ Diamonds, 2010. Creative Commons 3.0.

Karn, Raushan and Eswara Prasad. “Graphite Recycling Market: 2022 – 2031.” Allied Market Research Report A31811. https://www.alliedmarketresearch.com/graphite-recycling-market-A31811

Nobel Prize. “The Nobel Prize in Physics 2010.” https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2010/summary/

Novoselov, K. S. et al., “Electric Field Effect in Atomically Thin Carbon Films.” 22 October 2004, Science, Volume 306, Issue 5696, pages: 666-669. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1102896

Shang, Zhen, et al. “Recycling of spent lithium-ion batteries in view of graphite recovery: A review. 2024. eTransportation, Volume 20, May 2024, 100320. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2590116824000109

Smallman, R. E. (CBE), et al. “Carbon Range.” Modern Physical Metallurgy and Materials Engineering (Sixth Edition), 1999. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/carbon-range

Pencils.com. “What is a No. 2 Pencil?” https://pencils.com/pages/no-2-pencil

World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). Graphite and its Applications. 2023. ISBN: 978-92-805-3513-6. https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo-pub-1083-en-patent-landscape-report-graphite-and-its-applicatinos.pdf

Zhang, Y, Small, J.P., Pontius, W.V., Kim, P. “Fabrication and electric-field-dependent transport measurements of mesoscopic graphite devices.” Applied Physics Letters. 86 (7): 073104. https://arxiv.org/abs/cond-mat/0410314

Building the World Blog by Kathleen Lusk Brooke and Zoe G. Quinn is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 U