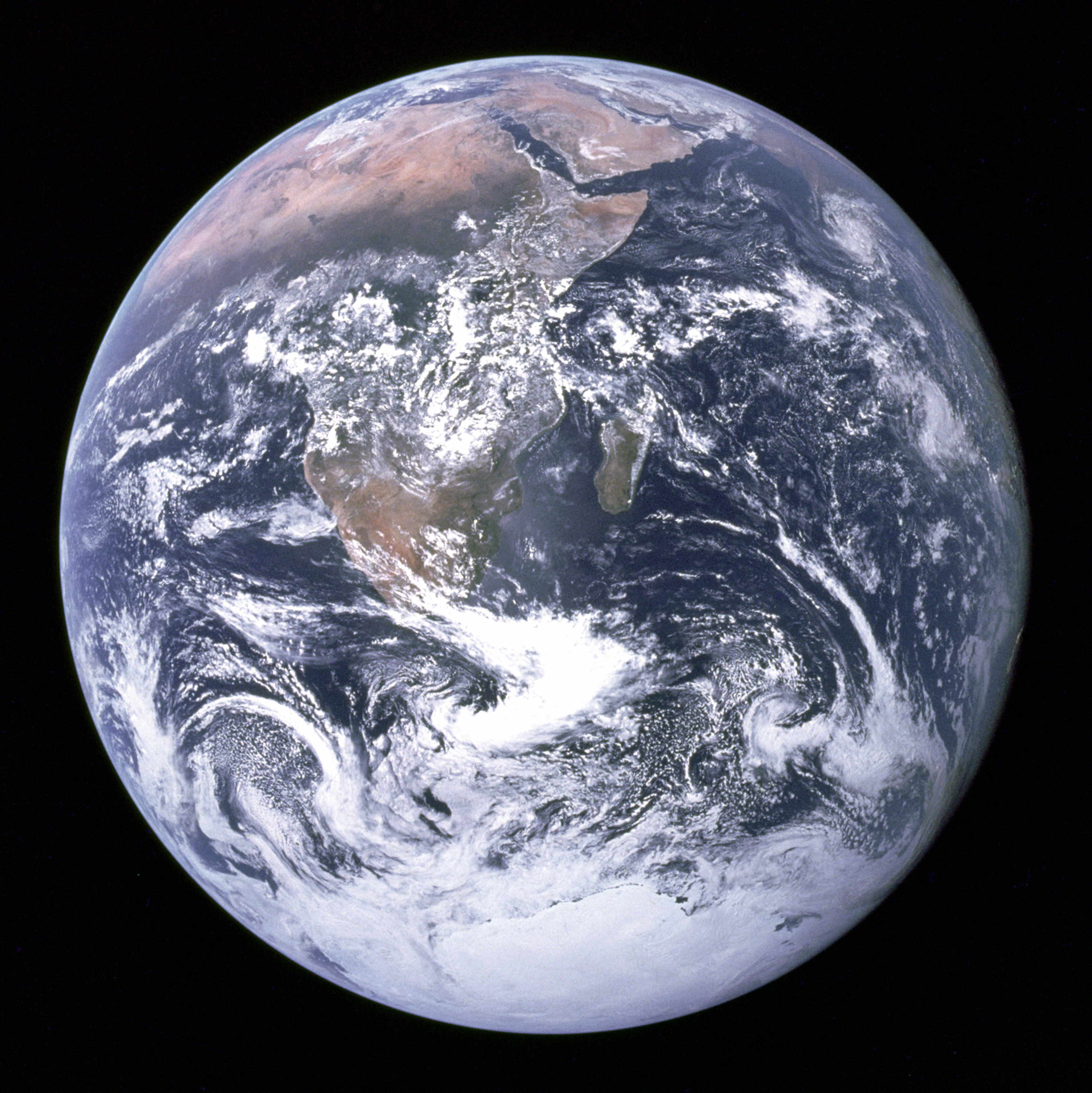

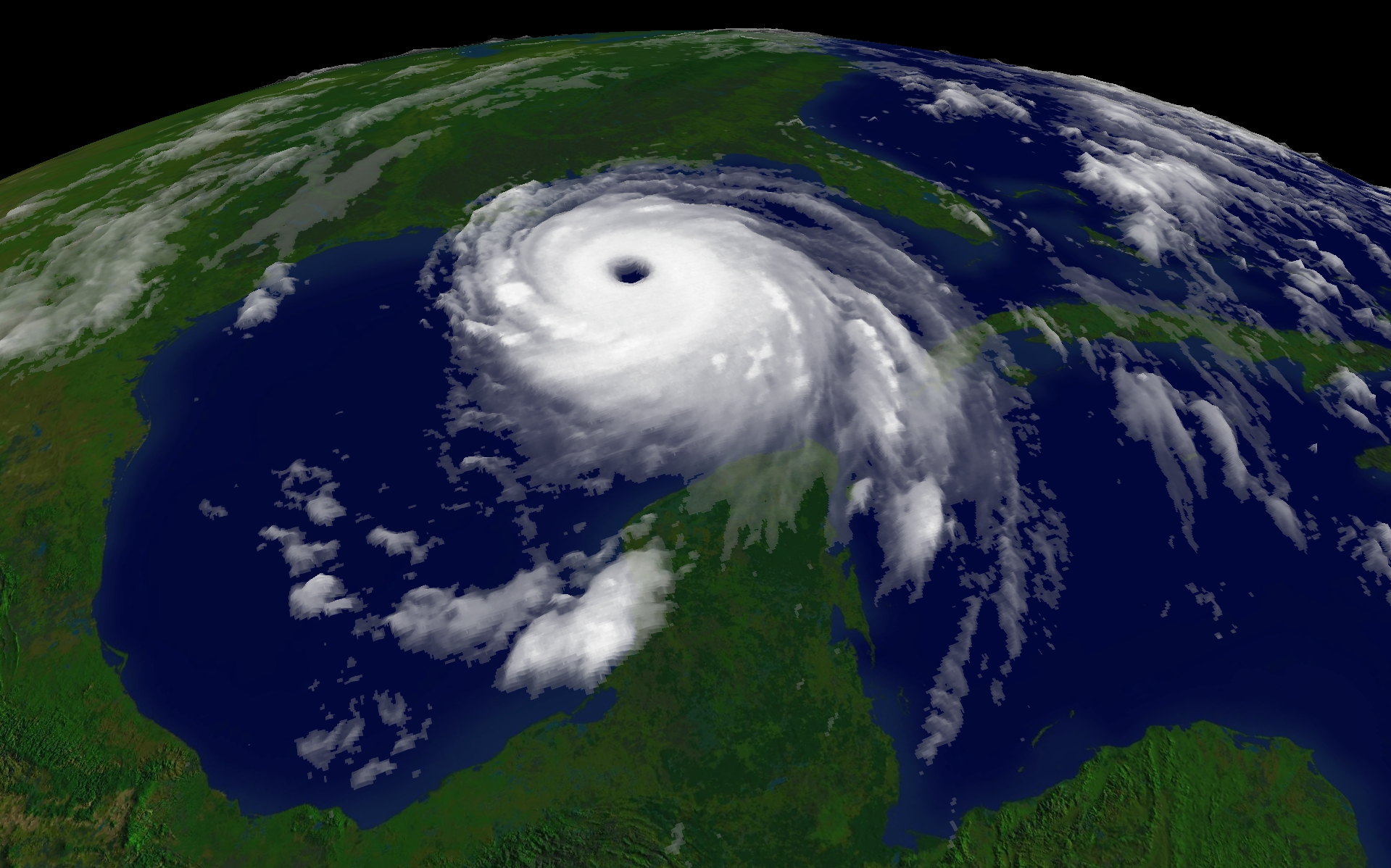

How can you grow the bountiful produce so treasured by Italy, and the world, in salty water? The worst drought in 70 years, caused by lack of snow and dearth of rain in Italy’s Po River valley, is choking once-verdant farmland. The Po River is 450 miles (650 kilometers) long, birthed in the Alps and running to the Adriatic Sea. One-third of Italy’s population lives near and depends upon the Po River, savoring the bounty of its farmland. Coursing fresh water from the Po usually overwhelms any drifting waves from the Adriatic, but with the Po’s drought, salty seawater is entering at a rate driving inland as far as 18 miles (30 kilometers). Crops are suffering, and so are cucina povera specialities like manzo all’olio or pisarei e faso.

Warming weather and drought have also wreaked havoc elsewhere in Italy. The Marmolada glacier in the Italian Alps collapsed on 4 July 2022, killing seven hikers, including two experienced mountain guides. in an avalanche of melting snow mixed with rocks. Prime Minister Mario Draghi stated the cause of the tragedy was climate change. Temperatures in the area have reduced glaciers by half since warming began. More avalanches are feared.

Hydroelectricity is also affected by drought. One-fifth of Italy’s energy comes from hydroelectric facilities, mainly located in the mountains. In the first four months of 2022, hydro power fell 40% (compared with 2021) due to drought. A water plant in Piacenza was closed on 21 June due to low water levels of the Po, the river that provides the water for the hydroelectric plant. At a time when Europe is trying to reduce dependence on imported energy, hydro power is essential.

What can be done? For now, a state of emergency declaration will truck water to 125 towns that must ration drinking water. In agricultural areas, drought-tolerant crops may become the new normal. Hydroelectricity may need a rethink and redesign: the Colorado River, Lake Mead, and the Hoover Dam have recently shown hydroelectric threats. Regarding melting glaciers, there is no quick fix. Water systems may be ready for Italian creativity and innovation, like those developed by ancient Romans who built the Aqueducts. Starting in 313 bce, Romans built 11 aqueducts, yielding about 200 gallons (750 liters) per person per day. That is more than the average American has: in 1975, the average was 150 gallons (563 liters) per day; in 2021, it was down to 115 gallons. Ancient Rome had such an abundance of water that the city became known for its fountains; composer Respighi’s Fountains of Rome.

Blackman, Deane R. and A. Trevor Hodge, eds. Frontinus’ Legacy: Essays on Frontinus’ De Aquis Urbis Romae. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2001.

Brooke, K. Lusk. Renewing the World: Water. Cambridge: Harvard Book Store, 2022. ISBN: 9798985035919. https://renewingtheworld.com

Evans, Harry B. Water Distribution in Ancient Rome. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994.

Parker, Jessica. “Italians wait for rain where longest river runs dry” BBC 8 July 2022. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-62096162

Patel, Kasha. “”Scenes from Italy’s worst drought in 70 years.” 7 July 2022. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/interactive/2022/drought-italy-po-worst-water/

Respighi, Ottorino. Fountains of Rome. Performed by Berlin Philharmonic. https://youtu.be/eGZ9oslaeak

Building the World Blog by Kathleen Lusk Brooke and Zoe G. Quinn is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Un