Aloha means both hello and goodbye. It’s a fitting word for transitions. Here are two case examples of solar policy changes in Hawaii and in Australia.

Hawaii is a perfect location for renewable energy: sunshine and wind are abundant. Yet, even with its natural advantages of sun and wind, Hawaii has been slow to move away from fossil fuels. But when electricity rates increased by 34% (from April 2021 to April 2022), homeowners who pay those hiked rates began to install solar. Now, more than one-third of all residential buildings in Hawaii have solar roofs. Could Hawaii serve as a case example of the challenges, and paths, to transitioning from fossil to renewable energy?

Policy matters. Just a few years ago, Hawaiian Electric, the largest power provider in the island state, lobbied to reduce rebates for rooftop solar. In 2015, utilities slashed revenues for excess energy sent to the grid by homeowners. But Hawaii has changed policies now, offering incentives up to $4,000 for Oahu residents to install home batteries for solar systems: the utilities now siphon excess power between 6pm – 8:30 pm, when demand peaks. Policy has encouraged solar adoption: legislating a Performance Based Regulation (PBR) for Hawaiian Electric now makes renewable sources easier to adopt and link, further aiding homeowners in their rooftop systems. Kauai has made the most progress: 70% of the island’s electricity is carbon-free and expected to increase to 90% with more solar and a hydroelectric plant that both creates and stores energy.

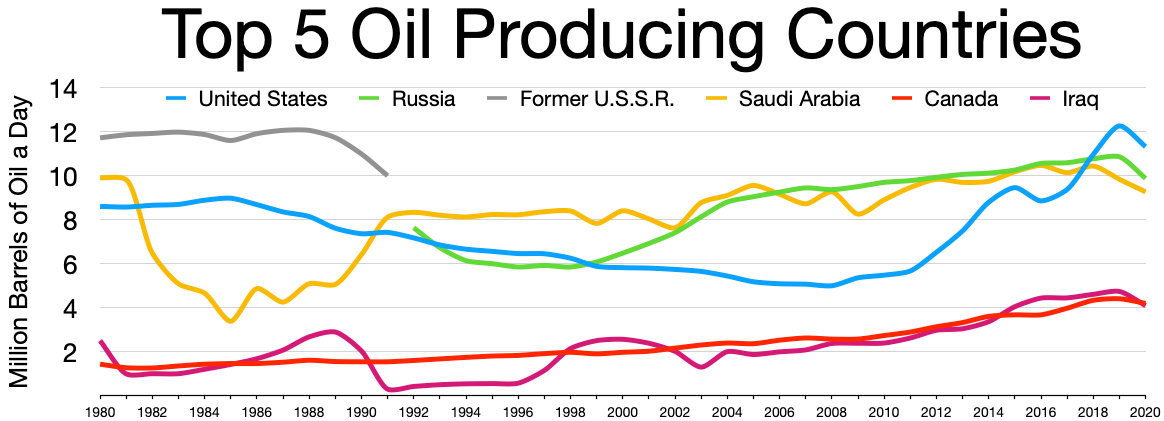

Geopolitics recently hastened the transition. In 2021, oil-supplied power plants delivered two-thirds of Hawaii’s electricity. Most of that oil (80%) was imported from Russia (as well as Argentina and Libya), while 20% was obtained from Alaska. Further, Hawaii is about to close its major coal plant. Forces of war and threats to supply have turned Hawaii in the direction of the sun. There is still debate over what kind of solar is best: utilities prefer large-scale options; but macro-scale means large tracts of land, something Hawaii does not have in abundance. Hawaii has set a new goal to achieve 100% renewable energy sources: it is the first American state to do so. Recently, other states have set the same goal. Cities are making solar decisions ahead of states. Hawaii’s Honolulu has three solar panels per person; California’s Los Angeles ranked number one of 57 cities surveyed for total installed solar capacity in 2019, while Nevada’s Las Vegas is close behind. In 2019, more solar capacity was added to the U.S. grid than any other energy source.

Another place in the sun? Bondi Beach, Australia, home of Snowy Mountains Hydroelectric. Australia drew 76% of its total energy from fossil fuels in 2020 with a mix of coal (54%), gas (20%), and oil (2%). Australia plans to close its largest coal plant in 2025 (seven years earlier than scheduled) and is now picking up the pace in solar. Australia increased rooftop solar installations by 28% from 2019 to 2020 – one in four homes there have solar panels: incentives and grants, contributed to the change. By 2020, renewable energy reached 24% of Australia’s power array. How much did the Renewable Energy (Electricity) Act of 2000 accelerate the change? Will the 2022 election of a new Australian government advance climate action?

Hawaii and Australia may serve as examples of how natural resources like sun and wind interact with policy and geopolitics in a dynamic system influencing factors driving the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy. What kinds of laws and policies are needed to encourage change?

Australia, Federal Register of Legislation. “Renewable Energy (Electricity) Act 2000.” C2019C00061. https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2019C00061/Html/Text

Australian Government of Industry, Science, Energy, and Resources. “Australian electricity generation – fuel mix.” 2020. https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2019C00061/Html/Text

Environment America Research and Policy Center, and Frontier Group. “Shining Cities 2020: The Top U.S. Cities for Solar Energy.” 2020. https://environmentamerica.org/feature/ame/shining-cities-2020

Harlow, Casey. “Honolulu tops national list for solar energy generation.” 19 April 2022. Hawaii Public Radio. https://www.hawaiippublicradio.org/local-news/2022-04-19/honolulu-tops-national-list-for-solar-energy-generation

Hawaii Public Utilities Commission (PUC). “Performance Based Regulation (PBR).” Decision and Order No 37787, 17 May 2021. https://puc.hawaii.gov/energy/pbr/

Paul, Sonali. “Australia’s biggest coal-fired power plant to shut in 2025.” 16 February 2022. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/origin-shut-australias-biggest-coal-fired-power-plant-225-2022-02-16/

Penn, Ivan. “Hit Hard by High Energy Costs, Hawaii Looks to the Sun.” 30 May 2022. The New York Times.

Building the World Blog by Kathleen Lusk Brooke and Zoe G. Quinn is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Un