The largest energy investment in United States history just made history. Climate and energy policy, worth $369 billion, has been agreed. Incentives and actions in the bill are estimated to lower American carbon emissions by 40% by 2030.

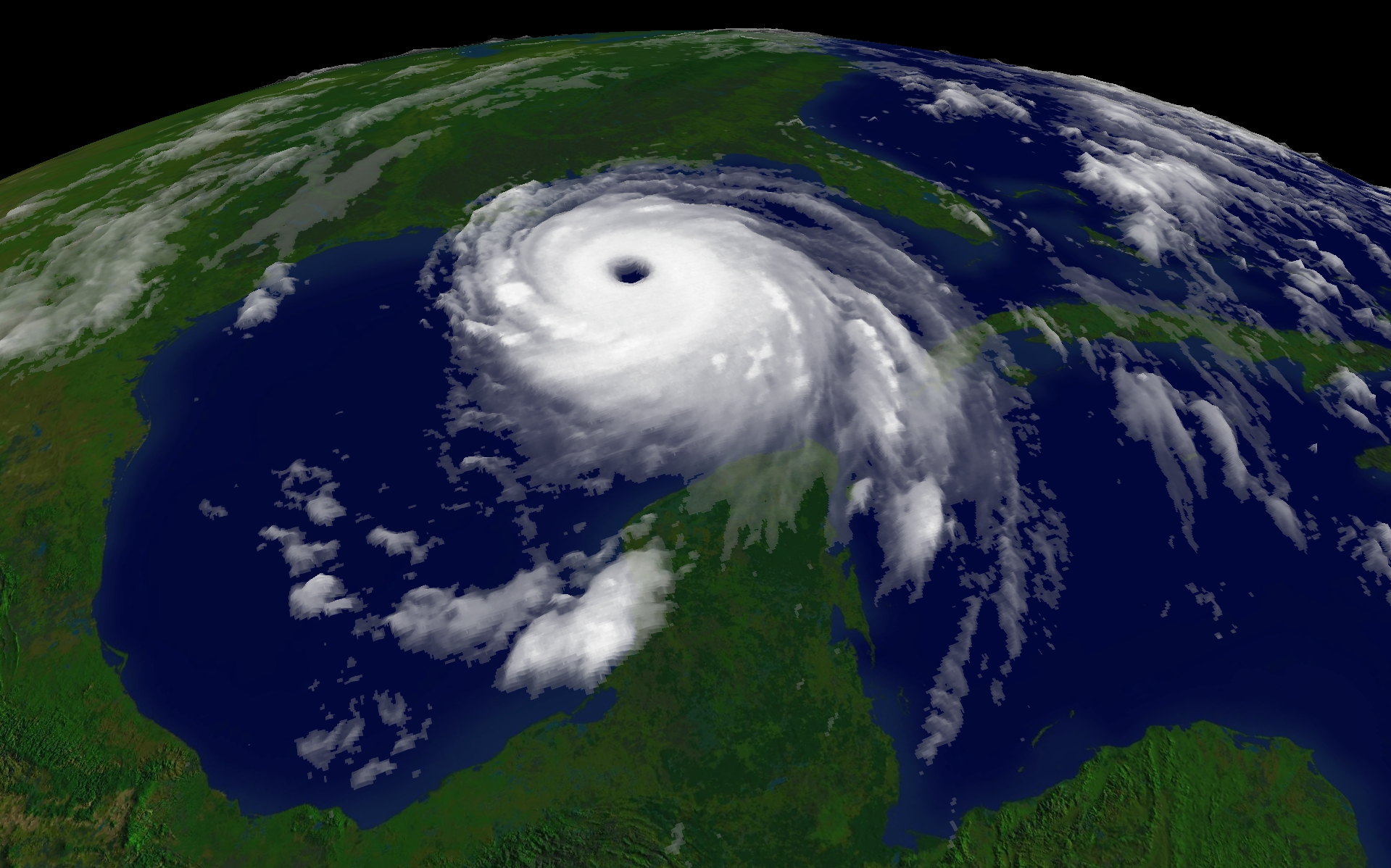

It’s not a minute too soon. At a time when Americans are battling drought, wildfires, flooding, heatwaves so intense that roads are melting, climate policy has grown urgent. And costly. The insurance industry reports costs of $39 billion in climate-related damage in the first half of 2022; that’s up from $31 billion just a year ago. Germany is turning off hot water in public taps, and all of Europe is bracing for a winter without Russian energy. The UK announced sea-level rise increased faster and more than expected. Nations, and regions, must work together to share energy resources and transitions.

Americans have risen to the challenge of urgent energy response before. The Manhattan Project, spurred by fear of disaster and damage yet unknown to humankind, marshaled the resources of a nation. The result was a new form of energy. The Clean Air Act of 1990 was the last big American environmental legislation: this will top that, bringing a plethora of incentives, subsidies and taxes. Some environmentalists lament one provision allowing drilling on 2 million acres of public land and 60 million acres of offshore seabed before use for renewable energy. While there are EV credits, the bill lacks similar encouragement for bikes, especially ebikes, knocking off an earlier credit of $900 in the earlier plan.

Here are some bill provisions, still pending passage:

POWER PLANTS – tax credits for zero-carbon power including battery, geothermal, nuclear, solar, wind.

CARBON SEQUESTRATION – tax credits for carbon capture.

EV – Buy a new electric car and get $7,500 off; buy a used Ev and get $4,000 off.

ENERGY EFFICIENT HOMES – the bill allocates $9billion for new energy-saving appliances, solar roofs, new air conditioning, heat pumps.

CLEAN MANUFACTURING – for domestic production of batteries, or key minerals like lithium, solar panels, or wind turbines, there is $60 billion waiting, plus an additional $500 million to assist with heat pumps and key minerals.

METHANE MITIGATION – plugging leaks from gas and oil wells, pipelines is key to stopping methane, a greenhouse gas more potent than carbon dioxide. This provision works by penalty – $900 per metric ton of emissions over federal limits by 2024, moving to $1,500 in 2026. On the plus side, $20 billion for farmers to reduce cow burps and agricultural gases.

DOING GOOD IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD – $60 billion for communities unfairly burdened by climate change.

In November 2022, the world will reconvene for COP 27 to report climate action steps. If passed into law, this new agreement will advance climate response for the United helping to achieve United Nations Sustainable Development Goal #13 – Climate Action.

Environmental Protection Agency, United States (EPA). “Clean Air Act.” 1990. https://www.epa.gov/clean-air-act-overview/clean-air-act-text

Nilsen, Ella. “Clean energy package would be biggest legislative climate investment in US history.” 28 July 2022. CNN.com. https://www.cnn.com/2022/07/28/politics/climate-deal-joe-manchin/index.html

Shao, Elena and Brad Plumer. “Seven Key Provisions in the Climate Deal.” 28 July 2022. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/28/climate/biden-climate-deal-key-provisions.html?referringSource=articleShare

Zipper, David. “There’s a maddening omission in the Senate Climate Bill: Congressional Democrats cannot imagine a world in which fewer people drive cars.” 29 July 2022. Slate.com. https://slate.com/business/2022/07/climate-bill-manchin-schumer-senate-ebikes-evs-cars.html

Building the World Blog by Kathleen Lusk Brooke and Zoe G. Quinn is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Un

“Wildfire in Santa Clarita, California.” Image: wikimedia.

“Wildfire in Santa Clarita, California.” Image: wikimedia. Cyclone Amphan May 2020. Image: wikimedia commons.

Cyclone Amphan May 2020. Image: wikimedia commons.