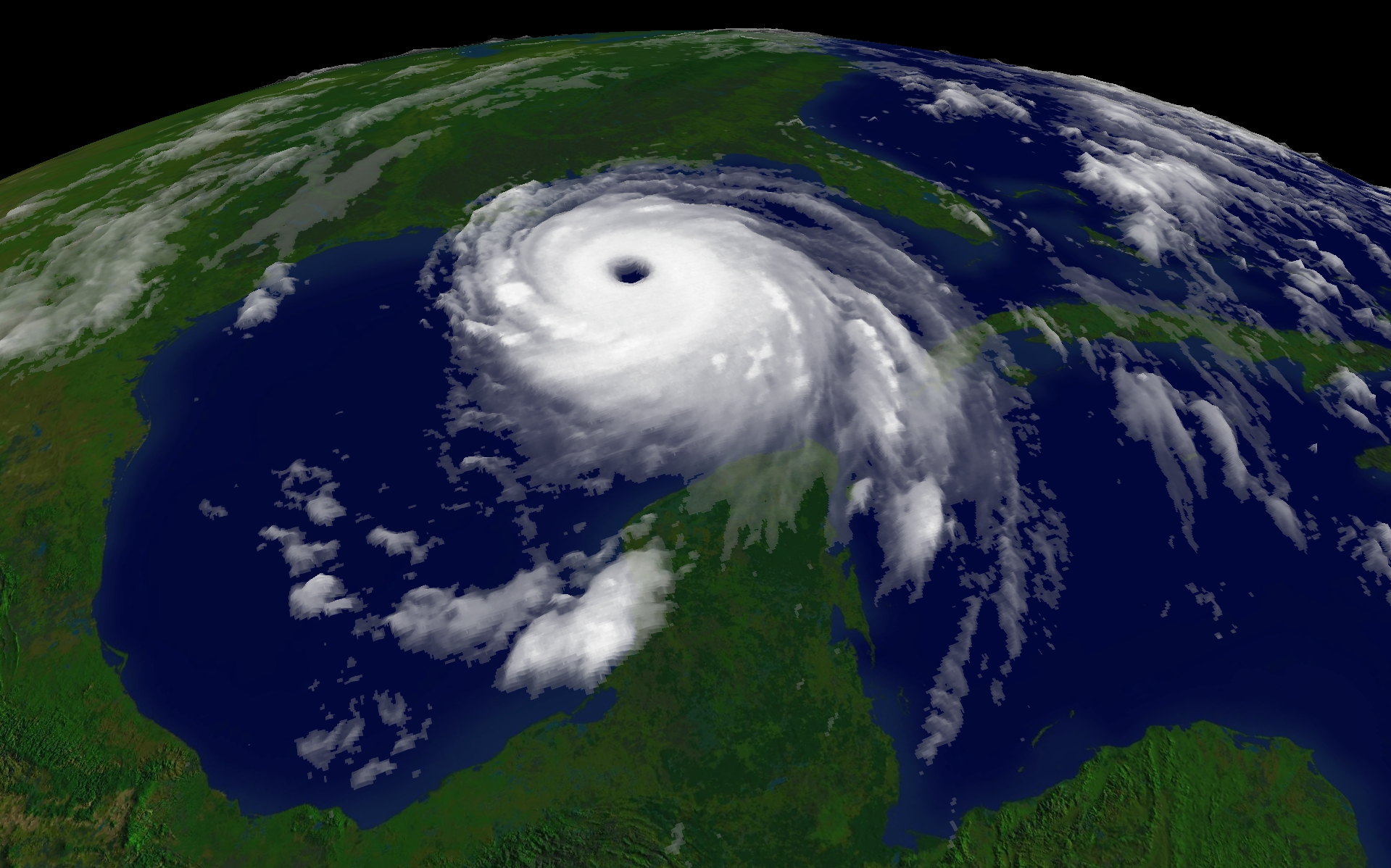

Hurricane Ida hit Louisiana, in August 2021, bringing severe wind and water. New Orleans was watching. After Hurricane Katrina, in 2005, the city built a flood-prevention system of gates, levees, pumps, and walls. Sixteen years later, almost to the day, Ida tested Katrina’s resilient infrastructure. The city emerged relatively unscathed( Hughes, 2021). But just 60 miles away, storm surge toppled the Lafourche Parish levee. Overwhelmed by floods, damaged sanitation and sewage systems threatened public health. The discrepancy between a prepared city and an unprotected town foretells the future of coastal communities in climate change.

It’s not just flooding. Even though New Orleans avoided Katrina’s flooding in Ida, there were other dire effects. Like power outages. Hundreds of thousands of people remained without electricity a week after the storm. Refrigerators were off, so were air-conditioners: in the 90 degree (F) heat, the situation was dangerous. Those who could escaped to nearby places with electricity for an “evacuation vacation.” Many were not so fortunate.

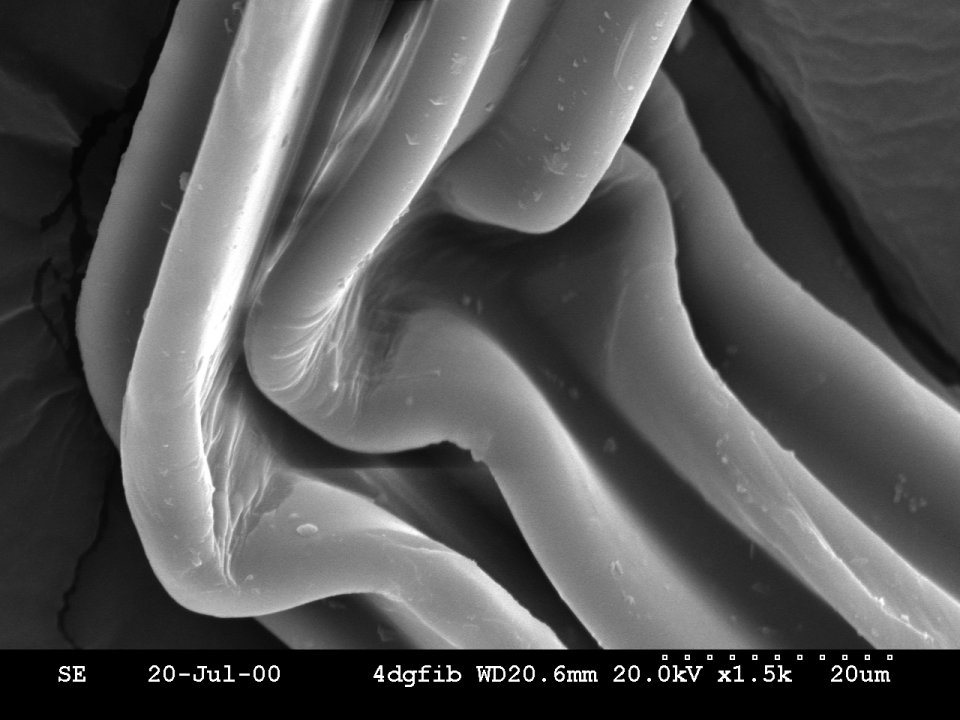

Coastal communities face an uncertain yet certain future. By 2040, providing storm-surge systems like sea walls for American cities with populations greater than 25,000 is estimated to cost $42 billion – that would include New Orleans. But what about Lafourche Parish? Protecting smaller communities and towns would raise the cost to $400 billion. (Flavelle 2021). Protecting against flooding is only part of the problem, however: wind damage to above-ground electrical poles, wires, and transformers is cause for alarm. During Hurricane Ida, 902,000 customers lost power when 22,000 power poles; 26,000 spans of wire, and 5,261 transformers were damaged or lost – more than Katrina, Zeta, and Delta combined (Hauck 2021).

Even with abundant funding, infrastructure takes time to build. Storms, however, will not stop. While rebuilding more resilient storm barrier and electrical systems, communities may look to the Protective Dikes and Land Reclamation practices of The Netherlands as a case example of immediate resilient response. The Dike Army (Dycken Waren), composed of residents responding together in times of need, was part of the system. As Louisiana, and other areas significantly damaged by Hurricane Ida, consider how to rebuild, it may be time to call to arms a new kind of Dike Army, perhaps a regional Civilian Climate Conservation Corps (4C), to serve and protect coastal communities and habitats: both terrestrial and marine. Disaster response would be in addition to the goals of the Civilian Climate Corps proposal of the US in January 2021. The 4C’s motto is up for a vote: some want “For Sea” and some like “Foresee.” What’s your vote?

Flavelle, Christopher. “With More Storms and Rising Seas, Which U.S. Cities Should Be Saved First?” 19 June 2019. The New York Times.

Hauck, Grace. “Week after Hurricane Ida’s landfall, hundreds of thousands still without power.” 5 September 2021. USA TODAY. https://wwwusatoday.com/story/news/nation/2021/09/05/hurricane-ida-louisiana-residents-without-power-families-homeless/5740682001/

White House, Biden-Harris. “Civilian Climate Corps.” 27 January 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/01/27/fact-sheet-president-biden-takes-executive-actions-to-tackle-the-climate-crisis-at-home-and-abroad-create-jobs-and-restore-scientific-integrity-across-federal-government/

Building the World Blog by Kathleen Lusk Brooke and Zoe G. Quinn is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unp