As the quest for clean energy continues, so does the search for battery components like cobalt, and other minerals. On land, mining has been an active industry, but resources are getting harder to access. Because land’s properties, and hidden treasures, are also present in the ocean, mining may be expanding to the seabed. The same thing happened in the energy sector earlier: oil wells were first drilled on land, then offshore.

The deep sea—and the seabed—are not the property of any single nation. Coastal countries do maintain proprietary rights to their waters to a distance of 200 nautical miles/230 land miles (370 km), known as an exclusive economic zone (EEZ). Within its EEZ, a country controls the rights to living and so-called “non-living” resources, including minerals. That means if a country is coastal, and it happens to have seabed minerals within the allotted reach, those resources are theirs to exploit without any permissions required.

Minerals needed to supply the ever- growing demand for electric batteries include cobalt. There are three main types of cobalt deposits found in the seabed:

- polymetallic nodules found in the seabed;

- sulfide deposits found around hydrothermal vents; and

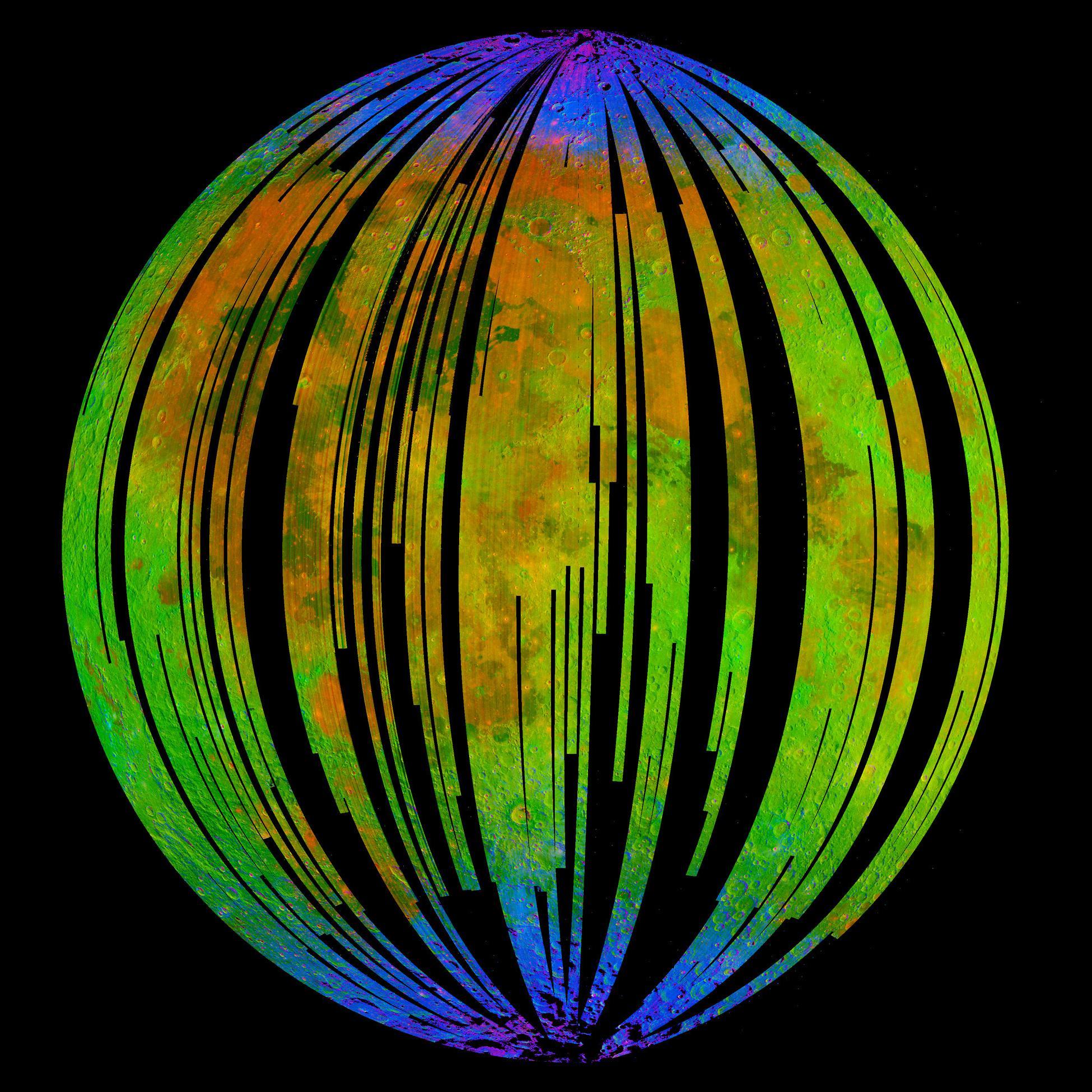

- ferromanganese crusts that line the sides of seamount crests and crusts.These areas contain cobalt, manganese, titanium, nickel, even gold. The relatively good news is that ferromanganese crusts can be found at more shallow depths of 0.25 to 3.0 miles (400 to 5,000 meters) where there is considerable volcanic action. A significant amount of cobalt deposits may lie within the EEZs of specific countries, so they would have access and rights there.

Resources outside of national boundaries belong to the whole world (even land-locked, non-coastal countries). These rights are regulated by the International Seabed Authority (ISA), established in 1994 as a follow-on to the UN Convention on the Law of Sea. Any country that is a signatory to UNCLOS (the U.S. is not, yet) may apply for an international seabed contract. ISA can grant two kinds of contracts: exploration and exploitation. The first gives permission to map where the desired minerals are and what might be necessary to reach and extract them. The second, exploitation, is mining. So far, all the contracts granted have been for exploration only. But that may soon change.

Nauru, third-smallest nation in the world, applied to ISA and was granted an exploration contract for Nauru Ocean Resources Inc. (NORI), a subsidiary company of DeepGreen, a Canadian company. DeepGreen merged with Sustainable Opportunities Acquisition Corporation, and the new firm was named The Metals Company (TMC), which quickly began working in an area of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) designated as NORI-D. The contract was to develop nickel, and perhaps later other minerals.

Many valuable minerals are contained in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) in international waters between Hawaii and Mexico. TMC estimates the CCZ area might contain the largest nickel deposit in the world. The polymetallic nodules there also contain manganese, copper, and cobalt. NORI embarked on 18 expeditions to evaluate resources as well as biodiversity, geochemistry, and the cyclic systems of nutrients. But mining the sea poses problems not yet encountered on land.

The Republic of Nauru recently gave notice to the ISA of NORI’s intention to mine the CCZ. Nauru’ s official letter, dated 25 June 2021, invoked the “Two Year Rule,” requiring ISA to complete its decision. There is a provision in the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), found in Section 1(15), that requires ISA to make a decision on a proposed contract within two years. Hence the informal name, “Two-Year Rule.” The rule is on the books as a safeguard to those who are ready to mine, but blocked when the approval process stalls.

Many have called for a moratorium, among them Sir David Attenborough as well as a number of marine science experts. But it would seem that mining may commence, soon. In March 2023, at the ISA general meeting, the Legal and Technical Committee began developing terms for exploitation contracts. In April 2023, ISA announced it would invite exploitation applications in July 2023.

If the international seabed belongs to everyone, how will the value of any minerals mined be shared? Certainly, private companies will need to be in partnership with sponsoring nations, like Nauru. And the costs of operations may be significant. But is there a plan for sharing some portion of the profits with the owners of the deep seabed – the world? Similarly, what is the plan for addressing potential loss and damage, if and when mining accidents or environmental degradation may occur? Will the work of Senator Sherry Rehman of Pakistan apply? If the international ocean and seabed belong to the world, a kind of blue commons, should rights be similar to those defined by the Outer Space Treaty? In our era of deep sea and deep space exploration (and exploitation), should we update our laws and rights concerning that which is shared by all humanity and nature? Might the insights of Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrum help us to determine how to govern the commons of international waters?

Finally, will there be a balancing of exploitation with preservation? Establishment of the High Seas Treaty created a legal mechanism for marine protection. The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) established an international legal instrument for conserving and sustaining Earth’s ecosystems. The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) set goals for 2030 and 2050. In June 2023, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) advanced a draft report on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction. Should ISA consider requiring those nations and private enterprise partners who are granted exploitation contracts to contribute to Marine Protected Areas? The ISA has established some, and others are in development. More on that, next post.

International Seabed Authority (ISA). “ISA Contract for Exploration: Public Information Template – NORI” https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1798562/000121390021020731/fs42021ex10-15_sustainable.htm

ISA. “Draft regulations on exploitation of mineral resources in the Area. Prepared by the Legal and Technical Commission” 2023. https://www.isa.org.jm/documents/isba-25-c-wp-1/

ISA. Overview VIDEO. “International Seabed Authority celebrates 25 Years.” July 2019. https://youtu.be/UUbQ56gbjlY

Shabahat, Elham. “Why Nauru Is Pushing the World Toward Deep-Sea Mining,” 14 July 2021. Hakai Magazine. https://hakaimagazine.com/news/why-nauru-is-pushing-the-world-toward-deep-sea-mining/

Singh, Pradeep A. “The Invocation of the ‘Two-Year’ Rule’ at the International Seabed Authority: Legal Consequences and Implications” 18 July 222, The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law 27 (2022), p. 375-412. https://brill.com/view/journals/estu/article-p375_1.xml?languagej=en

United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity. “Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.” 15/4, December 2022. https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-15/cop-15-dec-04/en.pdf

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). https://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/closindx.hrm