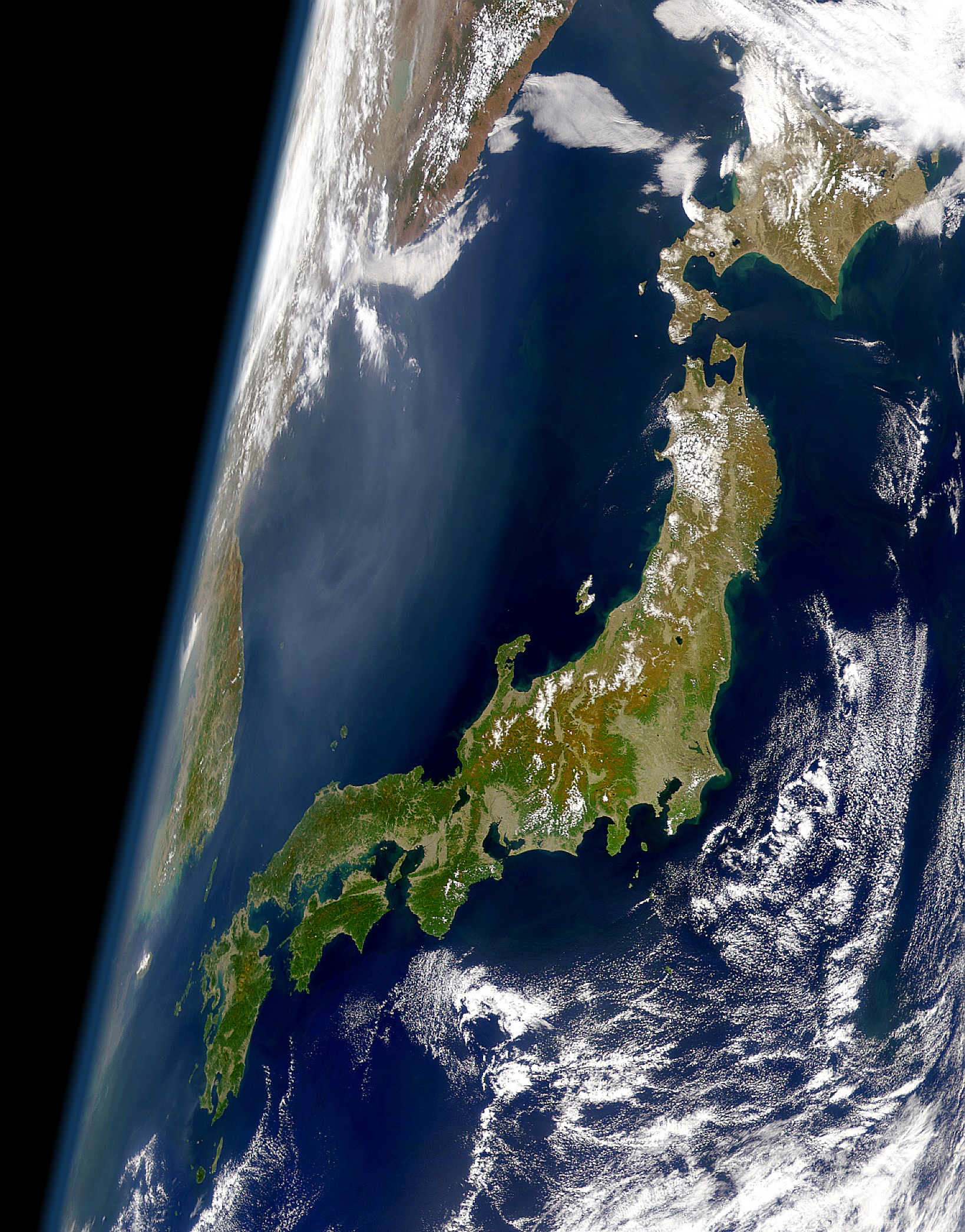

Want to talk trash? Look up. More than 25,000 pieces of defunct satellites, odd parts lost in extra-vehicular activity, bolts that floated off while repairing the International Space Station (ISS), are circling the Earth. And those are just the larger chunks (more than 4 inches in diameter). Go small and you go big: with 100,000,000 tiny but powerful bits flying at 17,000 mph (28,000 km). At that speed, even a paint chip could shatter a satellite – there are more than 8,000 of those in orbit, with 100,000 more planned by 2030.

Not long after the first satellite was launched in 1957 and COMSAT soon developed, the Kessler Syndrome, suggested by NASA scientists Donald J. Kessler and Burton G. Cour-Palais, reminded us that the more space objects we send into orbit, the more likely collisions will not just occur but pile up – the way a highway collision can create a multi-vehicle traffic jam. In space, such an event could cause outages of essential terrestrial communication systems.

On Earth, we have become familiar with the “reuse-repurpose-recycle” paradigm. But in space, we tend to shoot stuff up there and leave it to eventually degrade. Enter Astroscale and other space repair and debris removal businesses that offer a new paradigm: “inspect-service-remove.” Think of it as orbital road-service.

Legal precedent will help to guide the process. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty mentioned liability for damage sustained in space. The 1972 Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects developed and presented a regulatory framework. In 1975, the Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space mandated launching States to keep track of, and take responsibility for, their orbiting technology. The Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee may provide regulatory options. Space Traffic Management (STM) is a new industry that will help launchers to clean up their orbits.

Case Example: Astroscale. Founded in 2013 by Nobu Okada, Astroscale Holdings Inc (listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange as 186A) can service satellites in orbit, detecting potential problems and servicing devices while still operational. Beyond repair, the ADRAS-J can carry space junk safely out of orbit and return it to earth, where materials recycling may prove valuable. To make servicing easier, Astroscale manufactures a docking plate that enables in-orbit servicing and controlled removal, when needed.

In 2027, NewSpace India Limited (NSIL) and India’s Department of Space will launch In-situ Space Situational Awareness–Japan1 from the Satish Dhawan Space Center. The mission will inspect two large space debris objects now in orbit. In 2025, Astroscale received US Patent number 12,234,043 B2 for “Method and System for Multi-Object Space Debris Removal.”

NEW LEADERS in SPACE DEBRIS SERVICES include these companies. Some financial professionals note that while the satellite businesses has many entrants, space servicing and debris removal is an emerging market that will grow. Many of these new enterprises are at the private investment stage; when public, stock information is listed below:

Airbus. https://www.airbus.com Paris (AIR.PA) US OTC (EADSY)

Altius (subsidiary, Voyager). https://voyagertechnologies.com NYSE: VOYG

Artificial Brain. https://artificialbrain.in

Astroscale Holdings. https://astroscale.com/en Tokyo (186A)

Bull. https://bull-space.com

ClearSpace. https://clearspace.today/

D-Orbit. https://www.dorbit.space

Delta Infinite. https://www.delta-infinite.com

Digantara. https://www.diganara.co.in

iSEE. https://isee-space.ai

Kurs Orbital. https://kursorbital.com

LeoLabs. https://leolabs.space

Lockheed Martin. https://www.lockheedmartin.com NYSE: LMT

Northrup Grumman. https://www.northopgrumman.com NYSE: NOC

Orbit Guardians Corporation. https://orbitguardians.com

Orbital Lasers. https://www.orbitallasers.com

Paladin Space. https://www.paladinspace.com

Rocket Lab. https://rocketlabcorp.com NASDAQ (RKLB)

Space Cowboy. https://spacecowboy.today

Spaceflux. https://spaceflux.io

While space traffic management enterprises address already orbiting older designs, aerospace engineers are calling for more recyclable materials and devices. SpaceX pioneered reusable launch rockets. Now, more entrants are offering options.

JAXA/NASA astronaut Dr. Takao Doi, now a professor at Kyoto University, developed a satellite made of wood. LignoSat, biodegradable, can bypass the danger stage when re-entering Earth’s atmosphere. LignoSat is an example of a growing movement towards better materials for space.

But for larger space installations, there may be possibilities for reuse. Why not repurpose outdated space stations? The International Space Station will close in 2030. It took from 1998 to 2011 to construct and refine (see above video). The current plan is to let ISS crash into the Pacific Ocean. Any better ideas?

Astroscale. VIDEO. https://www.astroscale.com/en/missions/adras-j

Brooke, K. Lusk. “SPACE: Wood – Satellite Innovation.” 3 December 2024. Building the World Blog. https://blogs.umb.edu/buildingtheworld/2024/12/03/space-wood-satellite-innovation/

Cavalier, Andrew. “Launching Into the Future of Satellite Technology with SpaceX’s Reusable Rockets.” 13 December 2024. ABiresearch. https://www.abiresearch.com/blog/future-of-satellite-technology-spacex-reusable-rockets

European Union. “Commission consults experts on design of STM voluntary measures.” 17 September 2025. EU Defence Industry and Space. https://defence-industry-space.ec.europa.eu/commission-consults-experts-design-stm-voluntary-measures-2025-09-17_en

Horack, John M. “NASA will say goodbye to the International Space Station in 2030.” 13 October 2025. https://theconversation.com/nasa-will-say-goodbye-to-the-international-space-station-in-2030-and-welcome-in-the-age-of-commercial-space-stations-264936

Jah, Moriba. “Why We Need to Reduce, Reuse and Recycle in Space.” 21 January 2025. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-space-junk-crisis-needs-a-recycling-revolution/

Kessler, Donald J. and Burton G. Cour-Palais. “Collision frequency of artificial satellites: The creation of a debris belt.” June 1978. Journal of Geophysical Research, Volume 83, Issue A6, pages 2637-2646. http://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1978JGR….83.2637K/abstract

Koerth, Maggie. “How should we deal with space junk? Space recycling, of course” 8 December 2025. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2025/12/08/climate/space-junk-recycling-sustainability-satellites

Lloyd, Andrea. “JAXA’s First Wooden Satellite Deploys from Space Station.” 7 January 2025. NASA. https://www.nasa.gov/image-article-jaxas-first-wooden-satellite-deploys-from-space-station/

NASA. “Orbital Debris Program Office,” Astromaterials Research & Exploration Science. 2025. https://orbitaldebris.jsc.nasa.gov/faq/

Tamanna, Yasmin. “10 Top Space Debris Removal Companies to Watch in 2025.” 19 February 2025. StartUs Insights. https://www.startus-insights.com/innovators-guie/space-debris-removal-companies/

United Nations University. “Interconnected Disaster Risks: 5 Things You Should Know about Space Debris.” 26 February 2024. https://unu.edu/ehs/series/5-things-you-should-know-about-space-debris

Yang, Zhilin, et al., “Resource and material efficiency in the circular space economy.” 1 December 2025. Chem Circularity. https://www.cell.com/chem-circularity/fulltxt/S3051-2948(25)00001-5

Building the World Blog by Kathleen Lusk Brooke and Zoe G. Quinn is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 U