WHY UNITED STATES?

For the country that invented the mass-produced automobile, roads were a natural fascination. The Romans may have been the first to build throughways to unite territories, but it was an American soldier who stood out in the hot desert sun next to a broken down truck that envisioned and later created the United States Federal Highway System. The goal? Free trade, free transportation and free thought.

FROM HORSES TO HORSELESS CARRIAGES

In 1900, there were only about 8,000 cars in the country that would soon come to be known as the drive-through nation. Two years later, in 1902, when the American Automobile Association was founded, horses still outnumbered cars: 17 million steeds versus 23,000 vehicles. But October 1, 1908 saw the birth of a new landscape that would soon accommodate the wonder that Henry Ford rolled off the production line in Detroit, Michigan – the Model T automobile.

FARM TO TABLE

The idea of a national road system was not new; as early as 1862 a populist group called the Good Roads Movement lobbied Congress to pass a bill through the House and Senate to study road conditions; the effort languished. But thirty years later, Congress finally passed authorization for the secretary of agriculture to study roads to assure that the agricultural colleges had sufficient ways to transport crops. General Roy Stone set out to survey every state, interviewed all the governors, and compared rail rates for transporting goods versus the costs of building roads.

MACADAM, MADAME

There were regional efforts. In 1909, Wayne County, Michigan, not far from Henry Ford’s plant, built the world’s first mile of concrete highway. Roads heavy enough to hold vehicles were possible due to two Scottish engineers, John McAdam and Thomas Telford, who made roads with crushed stone bound with gravel set upon a base of large stones. This method became known as the macadamized system. Later, regulations would require even stronger bases using slag (a steel by-product) so heavy trucks could be accommodated. Some of those trucks might be carrying munitions, or so dreamt a young soldier.

62 DAYS IN THE HOT SUN

The soldier whose dream transformed the United States into a drive-thru country was once on convoy duty when his truck broke down on a dusty strip of dirt road somewhere in the middle of the country. The young lieutenant colonel and his Army buddy, Major Sereno Brett, might have regretted volunteering for the transcontinental convoy. It was a hot summer day when the truck, bumped and battered by chunks of gravel, caked with mud from being stuck in soggy embankments, ground to a halt. The soldier mopped his brow as he considered what might happen if the United States ever had to evacuate? If the army couldn’t get through, what about regular folks? Sixty two days later, the convoy detail ended when the trucks finally made it all the way from Washington, D.C. to San Francisco, CA. The year was 1919 and the soldier was Dwight Eisenhower.

Fast-forward to the 1940s when the Allied forces entered Germany and Eisenhower saw the Autobahn. A dream many years ago on the dusty road was replaced with a resolve: the United States must have an excellent, efficient road system.

When Eisenhower became President of the United States, he faced the need to create economic stimulus that would provide jobs for the returning soldiers who had served in the war and now were returning home to their families. Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) had mobilized unemployed young men to build dams, roads, and parks. Eisenhower decided instead to promote entrepreneurial opportunity, hiring local contractors to build sections of the Interstate near their homes and businesses.

DEFENSE

The Interstate System was renamed the “National System of Interstate and Defense Highways” according to section 108 because Eisenhower, being of military background, wanted to make sure the roads could accommodate heavy loads of munitions just in case the cold war of the 1950s heated up to a conflict requiring the transport of troops and weapons. It was this provision that made it necessary to strengthen roads with slag.

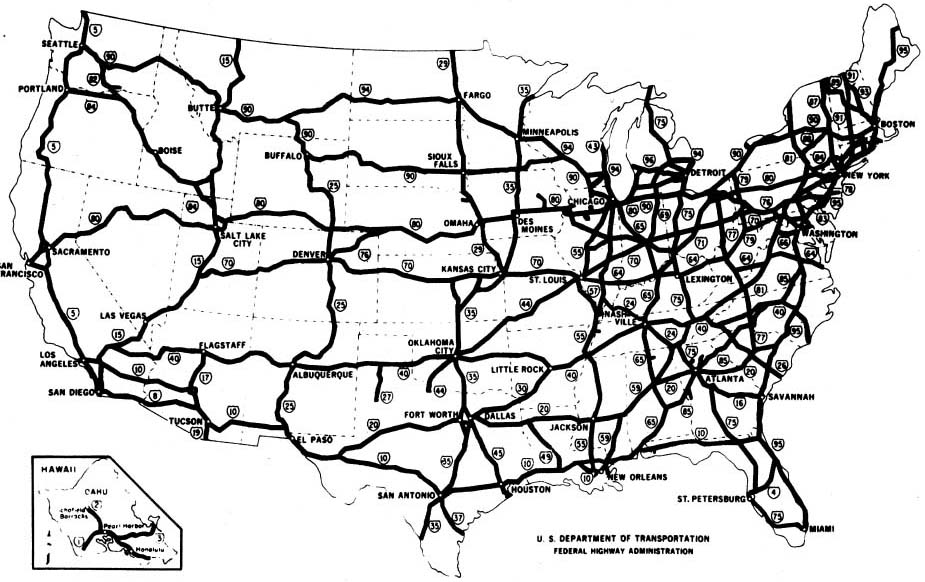

NUMBERS AS NAMES

Called by Secretary of Commerce Sinclair Weeks “the greatest public works program in the history of the world” the 1956 bill authorized $1.1billion to be allocated to the individual states who in turn hired local construction companies to build the interstate. There were just guidelines:

1) highways must have at least two lanes in each direction;

2) lanes must be 3.7 meters (12 feet) wide or more;

3) on the right lane there must be a paved shoulder at least 3 meters (10 feet) wide;

4) the roads must accommodate speeds between 81 and 113 kilometers (50-70 miles per hour).

It was to be a thoroughfare; no intersections or traffic signals. The system of standardization required naming and signage. It was decided to adopt a simple metric: all roads running north/south would have odd one-or two-digit numbers, while east/west routes would be even numbered beginning in the southern areas. Therefore a road number could convey directional information. For example, I-5 is a north/south road on the West Coast, while I-95 runs north/south on the East Coast. Roads that loop around cities would have 3-digit designations such as 128 around Boston.

TAXES, TOLLS, AND REVENUE

It wasn’t all spending; there was also money to be made. The accompanying “Title II- Highway Revenue Act of 1956” offered guidelines for taxes on diesel fuel, specialized motor fuels, and other taxable aspects. A little hike – from 2 cents a gallon up to a new rate of 3 cents was imposed. Tires were taxed at 8 cents a pound. Inner tubes for tires at 9 cents a pound. Gasoline was taxed at 3 cents a gallon. Vehicles were also taxed depending upon gross weight. Trucks, trailers, and buses required special categories of taxes.

SUCCESS?

By 1998, the interstate system comprised 74,567 kilometers (46,334 miles) of roads. Clearly, American preferred the highways to the byways; the entire National Highway System (interstates plus federally aided highways) totaled 257,645 kilometers or 160,093 miles and accounted for 24% percent of U.S. vehicular travel.

But when seen from an aerial view, the grid pattern of north/south intersecting with east/west at 90-degree angles brings to future designers a question: would other forms be safer? One of Eisenhower’s concerns was the tragedy of highway accidents. In 1952, the president-elect reported that 37,500 men, women, and children had died in traffic accidents the year before; he compared the loss of life to casualties of battle he knew too well as a general. It was Eisenhower’s belief that a safe interstate with no stoplights and a clearly divided highway with safe shoulder provisions would save lives.

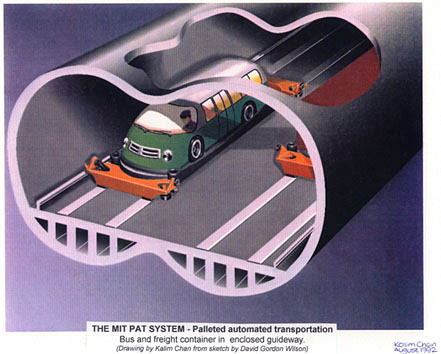

Might future highways take advantage of a plan developed by David Gordon Wilson of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology? A system of palleted automated transport (PAT) would move on independent guideways with motor vehicles exiting at selected points. Each pallet would be equipped with a differential electric motor, and therefore collisions on the PAT would be rendered physically impossible. Perhaps an advanced pallet system could take advantage of magnetic levitation.

Document of Authorization

On February 22, 1955, Eisenhower addressed Congress with this speech:

Our unity as a nation is sustained by free communication of thought and by easy transportation of people and goods. The ceaseless flow of information throughout the republic is matched by individual and commercial movement over a vast system of interconnected highways crisscrossing the country and joining at our national borders with friendly neighbors to the north and south. Together, the united forces of our communication and transportation systems are dynamic elements in the very name we bear – United States. Without them, we would be a mere alliance of many separate parts.

– See Building the World, pp 374-5.

VOICES OF THE FUTURE: Discussion and Implications

Drive-Through Nation: Do Americans spend too much time in cars? Eisenhower linked driving with freedom, but is there now such congestion that trains or other collective transport modes might define a new era? Or should roads become palleted highways that would allow individual travel that is safer and more environmentally beneficial?

Shovel-Ready Employment Programs: Which approach is more effective: Roosevelt’s CCC in which unemployed young people lived in government camps to build roads and parks or Eisenhower’s plan for small businesses to construct highways through local contracts? Is there a third option that combines both? Unemployment troubles America, Europe and many other areas of the world. How can building projects, especially large transport systems, encourage development of jobs?

RESOURCES

To read the complete chapter, members of the University of Massachusetts Boston may access the e-book through Healey Library Catalog and ABC-CLIO here. Alternatively the volumes can be accessed at WorldCat, or at Amazon for purchase. Further resources are available onsite at the University of Massachusetts Boston, Healey Library, including some of following:

Building the World Collection Finding Aid

(* indicates printed in Notebook series)

Gutfreund, Owen D. Twentieth Century Sprawl: Highways and the Reshaping of the American Landscape. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Ritter, Joyce N., comp. “Development of the Interstate Program.” In America’s Highways: 1776-1996. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, 1976. Also at www.fhwa.dot.gov/byday/fhbd0511.htm.

Rose, Mark H. Interstate Express Highway Politics 1941-1989. Revised ed. Knoxville, University of Tennessee Press, 1990.

Seely, Bruce E. Building the American Highway System: Engineers as Policy Makers. Philadephia: Temple University Press, 1987.

Von Hagen, Victor Wolfgang. The Roads That Led to Rome. Cleveland, OH: World Publishing Company, 1967.

Wilson, David Gordon. “Palleted Automated Transportation – A View of Developments at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, “ IATSS Research 13, no. 1 (1989), p. 53-59.

Internet

Richard F. Weingraff of the Federal Highway Administration has written a history of the legislative process, with historic photos including Eisenhower standing at attention during the seminal 1919 cross-country convoy, see: http//www.tfhrc.gov/pubrds/summer96/p96su10.htm

To find information on American roads, with links to topics from Turner-Fairbank Research Center to Winter Maintenance Virtual Clearinghouse, see http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/fhwaweb.htm.

Joyce N. Ritter’s story of how highway statistics were developed as the basis for the interstate system is available at

http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ohim/1994/text/history.htm.

For details on concrete, slag, and other road construction techniques, see

http://www.fhwa0316.htm.

For highway accidents during the Eisenhower era,

http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/safetyin.htm.

For MacAdam and Telford,

http://www.greatachievements.org/greatachievemets/ga_11_2.html.

Building the World Blog by Kathleen Lusk Brooke and Zoe G Quinn is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.