Introduction

Hello, I am Yasmeen Khader, a second-year graduate student studying Critical Ethnic & Community Studies.

I wanted to focus on an exploration of ethnic studies and related subjects and topics in the Boston Union Teacher not only because it’s related to my major and area of interest, but also because I plan to pursue a career in education, and one of my main goals as an educator is to foster an inclusive classroom. I was interested to see how the BTU has historically incorporated subjects and topics of ethnic studies.

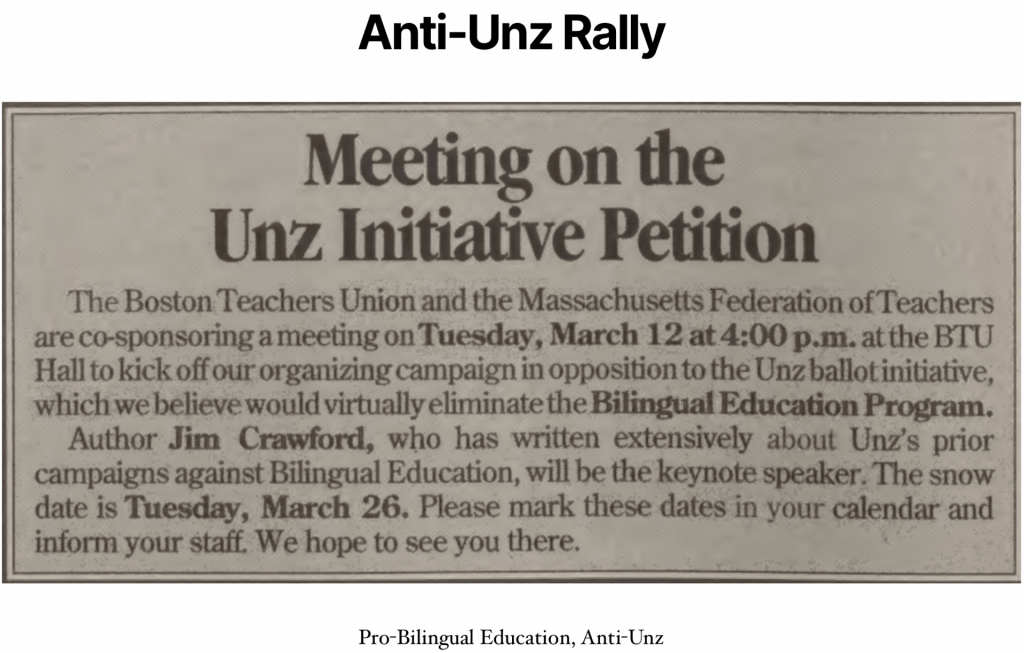

The topic of my digital exhibit is the Unz Initiative that was passed in 2002 to end bilingual education in Massachusetts. Getting to this specific topic was kind of a long time coming.

Exhibit Process

I started off my research by trying to plug phrases like “ethnic studies” and “culturally sustaining pedagogy” into the BTU archives, which yielded little to no relevant results. So, then I decided to search each of those keywords individually, and I got a ton of hits for the search term “culture.” I began screenshotting articles that discussed topics similar to what we now call ethnic studies and culturally sustaining pedagogy. I collected over 50 screenshots, which started to become a bit overwhelming. I worked very collaboratively with Professor Nicholas Juravich to narrow down my focus and hone in on a particular topic.

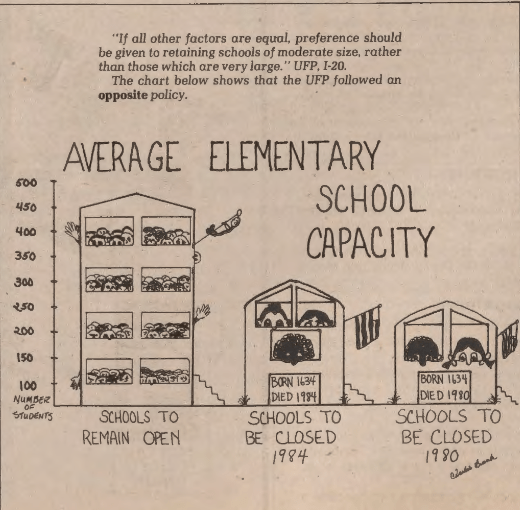

Professor Juravich and I noticed a trend in the 2000s of a big push to develop “classroom and school cultures.” When we considered why there might have been such a big shift and focus on culture, we realized that legislation that was being passed at this time was seriously negatively impacting bilingual, ELL, ESL, and immigrant students. In a period when schools were opening and closing rapidly because of federal state policy incentives, building school community was a counter move to support an increasingly diverse student body.

I then went back to the BTU archives, but this time I plugged in the terms “Unz” and “NCLB.” My archive for the exhibit consists mainly of screenshots of articles from the Boston Union Teacher, but I also incorporated several secondary sources such as articles and visuals. Some of my secondary sources include: video clips from a panel discussion from a campaign for high-school equity, a PBS clip on the Border Protection/Antiterrorism and Illegal Immigration Control Act of 2005 (or House Bill H.R. 4437, an anti-immigrant bill that passed in the house but died in the Senate), and information on the LOOK Act which replaced the Unz Initiative.

I dedicated an entire page in the exhibit to Berta Berriz because she has been outspoken in advocating for immigrant students and language learners since the 1980s. I included an audio clip from an interview from December 2021 that she did with Professor Juravich and Betsy Drinan on her time as an educator at the Boston Teachers Union School, an article she posted in the Boston Union Teacher in 2002 on why teachers should oppose Unz, and an article she wrote for The Radical Teacher in 2006 on the effects of the Unz Initiative.

Reflection

In terms of the revisions to the digital exhibit, the main thing to do is add in a bit more of my own voice where there are big blocks of text from the Boston Union Teacher. Also, I need to make the timeline clearer, and let the reader know when the BTU is taking action to oppose the initiative before it passes, and then how the Union is responding after the passage. I could also possibly bring the section on Berta Berriz to the opening page of the exhibit, since she is a beloved BTU member, and her quotation is so powerful about the impact of the Unz initiative on her students. This would be a great way to highlight her voice and catch the eye of fellow BTU members.

As far as the future of this digital exhibit, even from the beginning of my research journey, I have always thought that it would be incredibly interesting and informational to explore how the history of ethnic studies and related topics have evolved in Boston Public Schools, the Boston Teachers Union, and the Boston Union Teacher. Unfortunately, given the scope of this graduate class, I was unable to compile this timeline in one semester.

Although I was unable to compile a comprehensive timeline, I did still gather a significant amount of research materials. Some of these materials are included in my first blogpost, “Reimagining Ethnic Studies in BPS.” This blogpost is connected to my digital exhibit because it explores the prevalence of ethnic studies and culturally sustaining pedagogies that are fostered in Boston Public Schools today. While my digital exhibit focuses on how the BTU had to battle for immigrant, ESL, and ELL student rights in the 2000s, my first blogpost focuses on the ways in which BPS currently aims to foster inclusive and diverse classrooms.

My digital exhibit is also connected to several other exhibits created by my classmates. The digital exhibit entitled, “Women’s Voices” also highlights Berta Berriz’s inspirational work and the achievements of Kathy Kelley. Similarly, the digital exhibit “Kathy Kelley v. Kevin White” expands upon Kathy Kelley’s work in the BTU. The digital exhibit “Snapshot: Desegregation 1974” is connected to mine because around this time culture began to be mentioned in the Boston Union Teacher and the BTU began to focus on the diversity of students, schools, and classrooms.

Finally, my digital exhibit connects to materials that we read in our History 682 class. Concepts from Michael Frisch’s (2011) article, “From A Shared Authority to the Digital Kitchen, and Back,” are pervasive throughout my digital exhibit. For example, his assertion that we are not the sole interpreters of public history, and that oral and public histories should be as accessible as possible are core theories that drive this project and myself as a graduate student. Additionally, Frisch’s (2011) notion that listening to oral histories is just as valuable and important as reading transcriptions of oral histories is a concept that I incorporated into my digital exhibit. This concept I fundamentally agreed with as a student of CECS. I was surprised to learn that historians often favor transcriptions of oral histories over the audio itself.