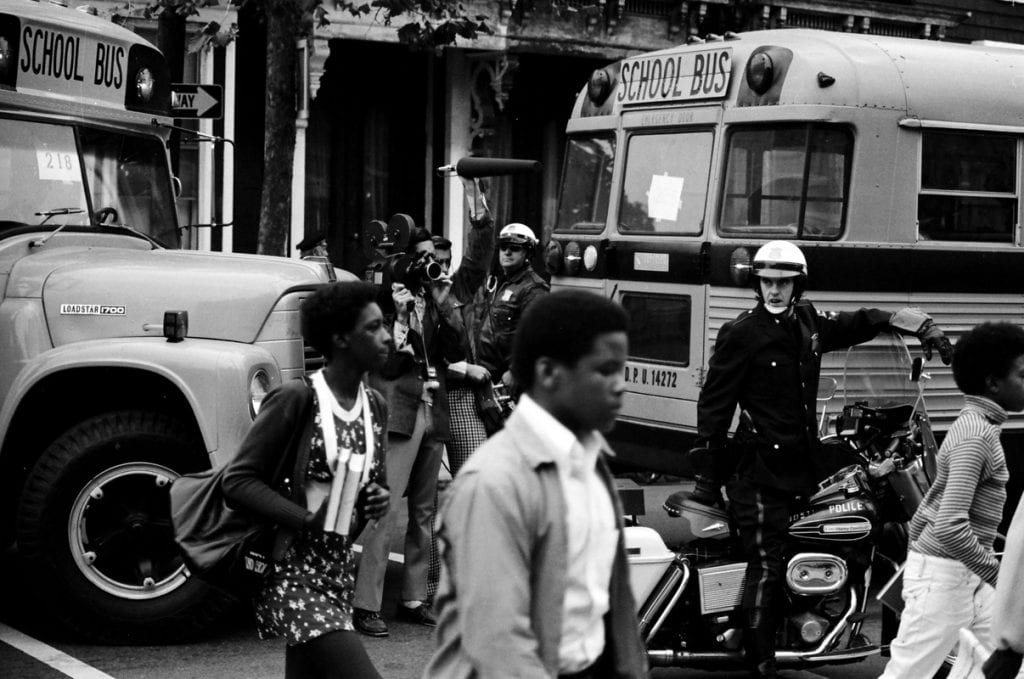

Boston Public Schools were not immune to the impact of segregation, even though memory of the Civil Rights Era centers on the American south. The Boston School Committee enabled what was called “de-facto segregation” in the city’s schools until 1974. De-facto segregation was the outcome of years of redlining and white flight within Boston that stratified the city into different neighborhoods based on race. Students attended the school closest to them geographically, which often meant that each school was attended primarily by students with a certain racial background. White students usually attended schools in South Boston and Charlestown, while Black students primarily attended schools in Roxbury, Hyde Park, and Dorchester.

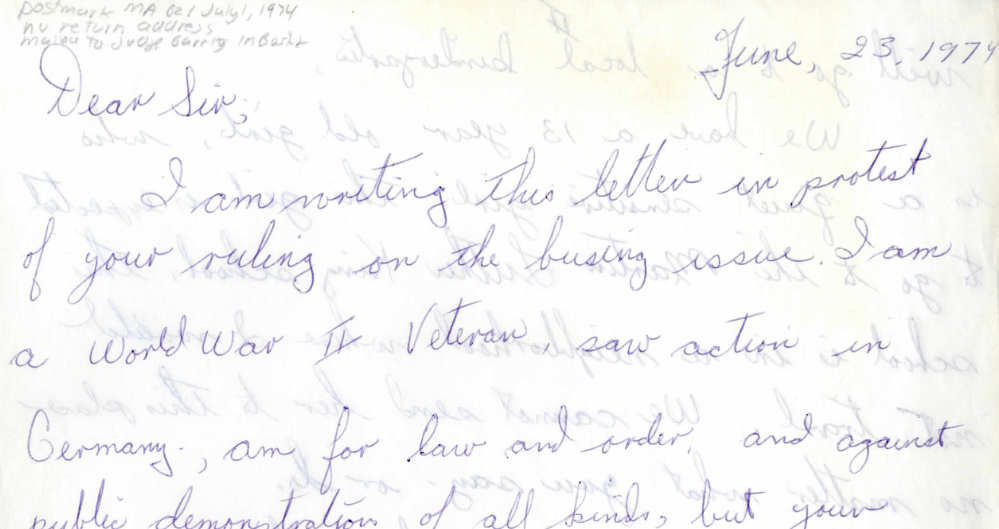

The NAACP challenged this ruling in Massachusetts District Court, and the case ended in 1974. There had already been public outcry from Black parents on the quality of schools attended by students of color, which were in worse condition than those white students attended. However, the gap between public opinion and opportunities for legal action was gapingly wide. When Judge W. Arthur Garrity ruled against the Boston School Committee on June 21, stating that Boston’s schools were in defiance of the Brown v. Board of Education decision that public schools must integrate, it shocked both Black and white communities. Their reactions ranged from positive to negative and everywhere in between.