In the March, 1979 edition of the Boston Union Teacher, the banner headline called attention to a formal protest issued to the Boston School Department over the closure of eleven elementary schools in the city, effective September, 1979. The announcement of closure was made in mid-February. The Boston Teachers Union was not alone in this protest, nor were they the first, following the Citywide Parent’s Advisory Council. Both the BTU and the CPAC accused the School Department of breaking promises that parents would be fully involved in what was termed the Unified Facilities Plan. What was this plan? And why did it involve closing schools? What did the BTU do to try and curtail its effects that they considered negative?

The Unified Facilities Plan

The first mention of the Unified Facilities Plan in the Boston Union Teacher came in December of 1977, the month after the original plan was supposed to be submitted before being granted a delay by Judge Garrity, who had previously ordered the desegregation of Boston Public Schools. The BUT claimed that nineteen schools were slated to be closed, while the Boston Globe claimed that the plan would only close seven. The stated reasons for the school closures was decreasing enrollment in Boston Public Schools, meaning that the same amount of money was being expended on fewer students. After numerous delays and protests, the Boston Globe reported in February, 1978, that parents had won input on the plans, the input that the BTU and CPAC claimed was being ignored the next year. The stated desire of parents was the right to retain access to a classic education, although what this was is never clearly stated.

The BTU’s View

In the view of the BTU, the closings were motivated primarily by efforts to cut city spending without harming the interests of those on the Boston Municipal Research Bureau’s Board of Directors. Specific accusations included that real estate investors were sacrificing schools to save one million dollars, instead of fixing property tax loopholes that would cost themselves fifty million dollars. Although there was not a direct accusation, the BTU insinuated that there may have been a racial motivation, as many of the schools slated for closure were those considered to be most successfully enforcing the desegregation orders. The Boston Globe reported similar ideas.

The next significant mention of the Unified Facilities Plan in the BUT came in September of 1979, the month in which the eleven schools were slated to be closed. The plan seems to have stalled continually, although it was never abandoned, instead being referred to an “…ever present threat…”, and members were urged to work with their communities to submit their own plans to prevent the worst effects. The final date by which a plan was to be submitted to Federal Court was December 1st, 1979, and so teachers were urged to submit their community plans well before that date.

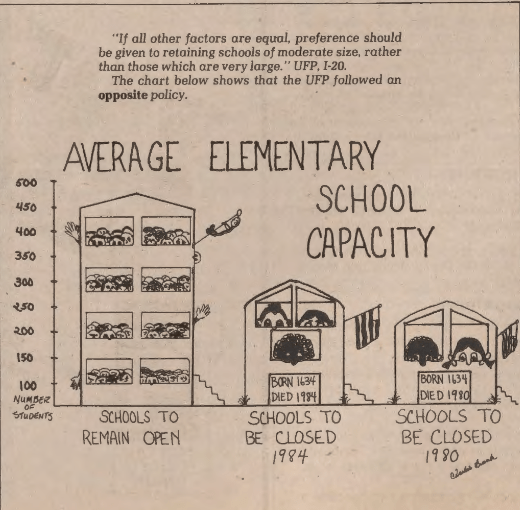

The December, 1979 issue included the longest and most detailed attack on the UFP up until that point, bashing its four years of failure, and its inconsistencies, chief among them the promise of supporting smaller schools rather than larger “educational warehouses”, but then closing the smallest of schools in order to repurpose the buildings while moving students to larger schools, increasing class sizes and teacher responsibilities while degrading the quality of education. It seems less than coincidental that articles noting the falling morale of Boston’s teachers appeared alongside many of these articles. Whether this was intentional propaganda on the part of the BTU, or whether the UFP coincided with a watershed moment in teacher and local government relations is difficult to say.

The cycle of proposing school closures, resulting in teacher and parent backlash continued until the mid-1980s.