Published May 3, 2022 by Eleanor Katari and Ari Branz

The 1970-1980s were a tumultuous time for Boston schools, the site of contentious battles around desegregation. The focus on the experiences of students and parents during this time overlooks a key piece of the puzzle – the experiences of Black teachers in the Boston Public Schools.

The Boston Public School system had a history of discriminating against educators of color in the hiring process.

Brenda Chaney, a longtime Black educator, reflected on the difficulties of being hired as a Black teacher in the 1960s, in an oral history in 2020:

“I have a sister-in-law who was an educator since 1966, and she had to fight her way to get to be a teacher… They did not hire teachers of color.” (Chaney 2020).

A Segregated Teaching Corps

Black parents had fought for decades to end de facto segregation in the Boston Public Schools. In 1974, during a time of nationwide civil rights protests and litigation, United States District Court Judge Arthur Garrity released a lengthy decision aimed at desegregating the Boston Public Schools.

The decision detailed how the School District had discriminated against and segregated Black educators. In the early 1960s, only about 1% of teachers were Black. In 1972-73, of the 4,243 permanent teachers in Boston, only 231 (5.4%) were Black. The next year, 1973-74, 7.1% of teachers were Black although 35% of students in the district were Black, and three-quarters of the Black teachers in Boston worked in majority-Black schools (Garrity 1974).

Even by 1974, a whopping 81 of 201 schools had never had a Black teacher. Garrity concluded that the “plaintiffs proved beyond question that racial segregation exists in parts of the Boston School system,” including amongst faculty and staff. (Garrity 1974).

In 1973-74, only 7.1% of Boston Public School teachers were Black, even though 35% of students in the district were Black.

Approximately 3/4 of Black teachers taught at majority-Black schools.

A Brief Overview

This later article by Ed Doherty from the March 1987 issue of the Boston Union Teacher provides a brisk overview of the overall issues and process:

“In 1974, Federal Court Judge W. Arthur Garrity found the Boston School Committee guilty of violating the United States Constitution in the manner in which it operated its public school system. The Judge came to this conclusion after a lengthy trial involving many witnesses and hundreds of pages of documented evidence.

Judge Garrity found at that time that the Boston School Department was running a dual system. Black and white children, even those living in the same community, e.g., Mattapan or Dorchester, were placed on different assignment tracks. One track led to all-black elementary schools which “fed” black middle schools which sent most of their graduates to predominantly black high schools. White children were sent off in a different direction to schools which were virtually all white.

There were, of course, a few exceptions to this tracking because black and white children did attend school together at some of the city-wide schools. These few exceptions aside, the Judge was correct in his finding that the Boston Public Schools deliberately segregated black and white students.

The Judge also found that the physical conditions of schools attended by black students and the resources allocated to those schools were inferior to those attended by whites. Further, Judge Garrity determined that the teaching staff assigned to predominantly black schools were less experienced and consequently less qualified. Finally, the Federal Court cited the School Department’s record of discriminating against blacks in its hiring and promotional practices.

In June of 1975 Judge Garrity issued his orders to remedy the Constitutional violations which he had found. These Desegregation Orders were designed to put an end to Boston’s dual school system and to create a unitary school system in Boston. A unitary school system is one in which every child is granted equal access to educational opportunities within the school district.” (Doherty, 1987)

While by 1987 the union leadership was ready to admit that Judge Garrity’s orders had some merit, during 1981 the response was much more mixed and contentious.

Impact on Black Educators

Judge Garrity found that among the reasons for the low percentages of Black teachers in Boston were “inadequate minority recruitment efforts, and the reputation of Boston as an anti-Black, segregated school system” (Garrity 1975).

Several months after his initial decision, on January 28, 1975, Garrity issued a supplementing opinion, to address the segregation amongst teachers. Judge Garrity ordered the hiring of one Black teacher for every white teacher, if qualified Black teachers were available. The court adopted a goal of 20% Black teachers, the approximate percentage of Black residents of Boston in the 1970 census. (Garrity 1975). Garrity also required the district to immediately hire 280 permanent Black teachers.

Judge Garrity ordered the hiring of one Black teacher for every white teacher, if qualified Black teachers were available.

Victoria Robinson, one of the teachers hired in 1975 in direct response to Judge Garrity’s orders, shared her experiences in the January 1975 issue of the Boston Union Teacher. She called the summer of 1974 “a time when the Boston Public Schools recruited and hired more black and non-white teachers in its history” and called it “an attempt to correct its disturbingly poor record of hiring non-white teachers and administrators.”

Victoria was understanding of the situation, saying, “Being one of the newly hired teachers, I found that the problems that I encountered were, on the average, understandable considering the chaotic state the School Department was in throughout late summer and fall.”

Nonetheless, she felt that herself and other newly-hired minority teachers were often hired at the very last minute, and then dropped into the middle of a chaotic situation with very little guidance or information about what to expect: “Many of us found that this coupled with extremely late appointments which were, by and large, the day of school opening for teachers and later, added to the general confusion.”

Overall, though, Victoria Robinson felt that the Boston Public Schools were now moving in the right direction. She writes that “Although such action resulted from the implementation of the Racial Imbalance Act rather than the School Department itself recognizing and attempting to deal with its inequitable hiring practices, many qualified non-white teachers were provided an opportunity to practice their craft.” (Robinson, 1975)

The Boston Teachers Union (BTU) and the Boston School Committee (BSC), however, were not ready to embrace this new reality. In fact, in the coming years, the BTU fought Garrity’s faculty desegregation orders at nearly every turn. In 1974, the BTU filed a response to the Judge’s decision, arguing that increased recruitment and training of Black educators should be sufficient, without the use of “quotas or preferential hiring.” (McMahon 1974).

Later, the BTU and the Boston School Committee (BSC) both argued in separate appeals that Judge Garrity’s goal of hiring 20% Black teachers was unreasonably high. They argued that a more reasonable target could be based on the labor pool of college students and recent graduates in the Boston Area (~12%), or on the percentage of all Black college graduates in the Boston area (5.25%).

But the appeals were rejected, and the court argued that the BTU was missing the point. Writing for the Court, Chief Judge Frank Coffin affirmed Garrity’s decision: “[the BTU’s] argument fundamentally misapprehends the nature of this case. The plaintiffs are not the Black teachers or would-be teachers who have been discriminated against because of their race… it is the rights of [Black Boston Public Schools children] that this order is intended to protect” (Coffin 1976).

“The plaintiffs are not the Black teachers or would-be teachers who have been discriminated against because of their race… it is the rights of [Black Boston Public Schools children] that this order is intended to protect“

Conflict Between Two Types of “Rights”

At issue was a fundamental conflict between two competing sets of rights: Civil Rights and Contract Rights. The BTU had only won collective bargaining rights in 1965, and they were protective of their hard-won contract gains. A key piece of educators’ contracts, and indeed of nearly all union contracts, is the idea of seniority or tenure. The offer of greater employment stability is a major incentive to join and support the union. In defending seniority rights, the BTU was fighting for a central tenet of labor rights, attempting to prove to existing and future members that it was worth supporting the union, and that it could follow through on its promises.

Judge Garrity’s ruling argued that the right to tenure or seniority, in this instance, bumped up against another fundamental right, the right of students to be taught in a non-segregated environment.

The BTU disagreed with Judge Garrity and Judge Coffin’s logic for years to come, and the BTU continued to file challenges to Judge Garrity’s order.

Two Tiers of Teachers

Besides teaching at segregated schools, the Boston Public Schools teaching corps was segregated in another way, as well: “permanent” (also sometimes called “professional”) teachers vs. “provisional” teachers. Permanent teachers held a state board license, and were entitled to more rights under state law and the union contract, as well as a higher rate of pay than provisional teachers. Provisional teachers lacked state licensure, made less money, and were easier to fire. After three years with provisional status, teachers were granted tenure, or “permanent” status under MA state law.

Because Black educators in Boston tended to have been hired more recently than white teachers, fewer Black teachers had full “permanent” status. In 1972-1973, 35% of Black teachers (125 out of 356) were provisional, higher than the overall percentage in the district (Garrity 1974).

But in 1975, something unusual happened: Boston Public Schools entirely stopped hiring new permanent teachers, and increased its hiring of new provisional teachers. This meant that as a larger number of Black teachers were brought on, they were disproportionately provisional.

In 1975, Boston Public Schools entirely stopped hiring new permanent teachers, and increased its hiring of new provisional teachers. This meant that as a larger number of Black teachers were brought on, they were disproportionately provisional.

The School District had found a loophole in Garrity’s order that one Black teacher be hired for every white teacher. The school department could rehire any provisional teacher employed the year before and not be bound by Judge Garrity’s 1:1 requirement, which applied only to permanent positions. Defeating the spirit of Judge Garrity’s order, the school department moved forward by rehiring a disproportionate number of white provisional teachers.

The BTU then doubled-down on protecting seniority rights in their contract negotiations, even going on strike in 1975 to win a contract demand guarantee that no tenured teachers would be laid off. In essence, by focusing on contract gains for permanent but not provisional educators, the union was putting its energy into representing only a part of its membership – and that part was disproportionately white.

Black educators were left feeling unrepresented, as the union actively worked against Judge Garrity’s orders aimed at creating a more integrated and representative faculty for Boston Public Schools.

Budget Crisis – Proposition 2 ½

By 1980, to add to the existing stressors, the Boston Public Schools were facing a fiscal crisis. Riding a wave of conservative dissatisfaction towards ‘big government’ in the wake of California’s pivotal passage of the Proposition 13 “tax revolt” bill, in 1980 Massachusetts voters passed Proposition 2 1/2, a property tax bill that drastically limited public revenues. The resulting budget cuts hit public schools and services particularly hard, and services and personnel were facing drastic cut-backs.

By early 1981, layoffs loomed in Boston. The budget cuts would necessitate some harsh choices. The dilemma was who to lay off: white teachers with more seniority and tenure, or black teachers hired more recently? Put another way, which should prevail: the BTU’s Collective Bargaining Agreement, or Judge Garrity’s court order mandating 20% Black representation in the teaching corps?

The BTU took a hard-line stance, insisting on strict seniority as the only criterion to guide the lay-off process.

Black Educators Organize

But Black educators in the BTU felt differently. Member Barbara Fields recalled in an Oral History that she brought her opinion to the BTU’s Executive Board meeting: “We questioned how, if in fact the union was for integrated education, they could justify going by strict seniority in the contract, which would mean that a majority of black and other minority teachers would be laid off.” (Fields, 2020).

Black educators had been organizing for a long time. They joined the Black Educators Alliance of Massachusetts (BEAM) and its legal arm, Concerned Black Educators of Boston (CBEB). As Barbara Fields recounted, during desegregation:

“BEAM provided the support, and also brought us together, so we didn’t feel so isolated. Because we were spread out all over the district, because the court order said you have to have a certain percentage of black teachers in every school. So at BEAM meetings we were able to come together, and coalesce, and get support from each other … it provided the emotional support, as well as the professional support.” (Fields 2021).

Eventually, BEAM became a locus of legal support for Black educators as well. Fields recalled: “At that time, BEAM had hired an attorney, Nancy Gertner, who later became a Federal Judge, to represent us in the court case. Because at that time, the BTU in court was taking the position against affirmative action” (Fields 2021)

On May 16th, 1981, CBEB sought an injunction from Judge Garrity to exclude Black teachers from any layoff orders until they comprised 25% of the District’s staff. According to the Globe, at that time in 1981, 961 out of Boston’s 5,000 teachers (19%) were black. The lawyer for CBEB, Nancy Gertner, told the paper that if the layoffs took place in reverse seniority, “several years of progress under the court orders will be undone overnight.” (Doherty 1981).

If the layoffs took place in reverse seniority, “several years of progress under the court orders will be undone overnight.”

Longtime BTU educator and activist Bob Marshall shared what it felt like to be a Black educator at this time: “Black educators had constant fights with the people running the BTU, and it was around race. And it got so bad that in 1981, we had to go out and hire a lawyer to sue the union to get the court order. That’s how bad it was. (Marshall 2021).

On June 2nd, 1981, Judge Garrity issued his three-part layoff order. First, layoffs should occur “in such a way that the system-wide percentage of black teachers will remain at the current level of 19.09%, and the system-wide percentage of other minority teachers will remain at its current level.” Second, “Blacks will receive an absolute preference for recall until a 20% figure is reached system-wide.” This meant that all recalled teachers would be Black, until the goal was reached. Finally, “Once this 20% figure is reached, no fewer than 20% of the teachers subsequently recalled or recruited will be black.” (Garrity 1981).

“The 710”

On August 18th, the School Committee voted to officially lay off 710 tenured white teachers, and a significant number of provisionals, nearly 1000 teachers in total.

The number “the 710” became an evocative rallying cry. It was felt to be an egregious over-ruling of key union contract gains to lay off tenured teachers while retaining teachers with less seniority. The rhetoric and outrage became racially charged, however, and the phrase “the 710” continues to have resonance with union members today.

Mary Ann Urban, a white teacher, recalled in an oral history, “Along that time came 1981 and the layoff of 710 white teachers, and the meetings involved with that and the list of, you know, the 710… I never got [a layoff notice] but a lot of my faculty did… ‘With a heavy heart and deep regret I must inform you that I am recommending that you be laid off from your position.’ And that led to a great deal of controversy” (Philip and Urban 2021).

But James “Timo” Phillip and other Black educators were concerned as well about the huge number of Black “provisional” teachers that were also losing their jobs as the result of the budget cuts.

In a joint interview with Mary Ann and Timo in 2020, even forty years after the events of 1981, you can still hear the emotion in their voices when they are talking about the impact of “1981” and “the 710.” Those numbers have a meaning and a resonance inside the Boston Teachers Union, in the same way that “9/11” has a meaning and a resonance in a larger American context. (Philip and Urban 2021)

Provisional Jobs Lost

Black educators within the BTU saw the layoffs very differently than both the BTU leadership and the press. BTU educator Barbara Fields explained her perspective:

“The way that it was framed, was that only white teachers were laid off. Because the white teachers who were laid off were permanent teachers, and they had seniority. The black teachers who were not rehired were provisional teachers because they were new to the district. They had not gotten to the point where they had tenure. So, you don’t lay off provisional teachers, you just don’t rehire them. White teachers, because they had tenure, they were laid off. So there was this big thing out there about the district is protecting black teachers and laying off white teachers. I used to always say, if you look at who had a job, and then didn’t have a job, it was a proportionate group of people, black and white, who were working one year and didn’t have a job the next year” (Fields 2021).

“You don’t lay off provisional teachers, you just don’t rehire them.”

Brenda Chaney echoed Fields in her narrative,

“Oh, boy, that was one of the worst times… the building I was working in, the teachers there were — I think there was only two Black people because I was working in a small building. And they were highly upset that the 710 of white teachers were being laid off. And they were keeping less senior Black teachers. They didn’t look at all the provisionals that they didn’t rehire. They didn’t look at that number. All the minority that were provisionals, they did not — there was more than 710 of them that they did not rehire” (Chaney 2020).

Will the BTU Strike?

On August 28, 1981, the BTU Executive Board, expressing concern about what it saw as contract violations, recommended that the union go out on strike the day before school was scheduled to start. BTU President Kathy Kelley’s public messaging invoked the common good for the students.

But BTU members, particularly Black educators, were far from united about the best steps to move forward. Edward Greer, the lawyer for the Concerned Black Educators of Boston (CBEB), objected to the union’s actions. Greer argued that Black teachers were full, dues-paying members of the union, and that “In spending union dues to pursue the appeal… the union is requiring Blacks to support an effort that could cost them their jobs.” Kelley rebutted: “We have clearly represented all the union members through the course of the years… that contract applies to all members. We have upheld the rights of all members and will continue to” (Kindleberger 1981c).

As the strike vote drew nearer, black educators made clear that voting for the strike was not in their best interests. A school principal and former president of the BEAM, Lloyd A. Leake, was not a union member but laid out the black educators’ logic clearly: “Let’s face it, if black teachers and other minorities join in a strike, they will be striking against themselves. If we were to be laid off strictly on seniority, up to 95% of the black and minority teachers would be wiped out” (Cohen and Rivas 1981). As CBEB’s lawyer, Nancy Gertner shared with the Globe, “Seniority is not color blind where there is not now and never has been equal access” (Kindleberger 1981g).

“Let’s face it, if black teachers and other minorities join in a strike, they will be striking against themselves. If we were to be laid off strictly on seniority, up to 95% of the black and minority teachers would be wiped out”

The First Strike Vote

On the morning of September 7th, 1981, the BTU was poised to take its strike vote. Union president Kathy Kelley projected confidence about the BTU’s unity. But BTU educators expressed far more hesitations. Besides the widening racial divide on this question, President Ronald Reagan’s recent crack-down and permanent firing of striking Air Traffic Controllers in PATCO signalled a new, less labor-friendly regime on the national level, and teachers were in sincere fear of losing their jobs if they went on strike. (Wood 1981).

All of these hesitations came to a head during the strike vote. BTU members took a vote to postpone the strike vote: functionally, the members chose not to take a position. The voting was close, though, with 1736 to 1570 voting to postpone. Three hours later, after several hundred teachers had left the auditorium,” the remaining members voted again, voting instead in favor of moving forward with the strike. (Kindleberger and Higgins 1981). The strike vote served to increase rather than decrease tensions. Many members felt suspicious of the re-vote, and the initial vote still displayed a high degree of disunity and disagreement. The decision was made to vote again in a few weeks. For BTU leadership, the public display of disunity within their membership dealt a devastating blow to their ability to credibly threaten a strike.

For black educators, the experience was painful. Brenda Chaney described the scene:

“I remember that we were all sitting together…. And all the Black teachers were saying like, no, we’re not voting for that. We got up to the mic… Timo [Phillips] and other minority teachers got up to the mic and spoke about how dare you think about using our money to … kick us out of the Union, to kick us out of our jobs. How dare you.” (Chaney 2020).

The Second Strike Vote

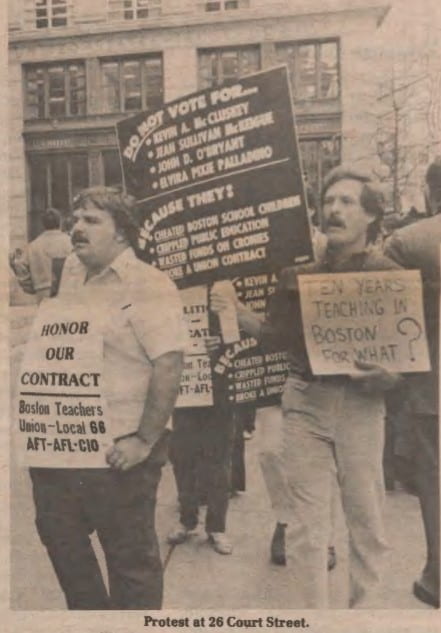

Tensions further escalated in the next few weeks. Schools opened on time, but teachers continued to protest the budget cuts and layoffs. A strike vote had only been postponed, not eliminated.

On Monday, September 14th, an informal rally of 200 laid-off teachers in front of City Hall descended into chaos as teachers attempted to enter Mayor White’s lobby. Police locked the protestors out, believing they were going to “come in and get the mayor if he didn’t come out to talk to them.” Ultimately, “two teachers were arrested and charged with assault and battery on police officers who were trying to keep them out of the building.” The front-page photo showing one of the arrests was not good publicity for the BTU. (Radin 1981).

On Sunday, September 20, the BTU gathered again for a full strike vote.

According to the Boston Globe’s recount of the closed meeting,

“The debate on the strike motion was rotated at six microphones, each manned by a sergeant at arms. Emotions peaked in pleas for unity and dire predictions of the union’s doom. Courage was a key word, strategy was another. Arguments flip-flopped. Some argued that if there was no strike the union would die. Others contended if there was a strike, it would kill the union. Some predicted a strike would ultimately improve the quality of education. Others charged a walkout immediately abandoned children deserving a chance to learn… several minority teachers vowed not to support a strike unless the union dropped its appeal of a federal court order upholding affirmative action. ‘It’s time to support affirmative action, if you want a united union,’ remarked Isaiah George, a black teacher with three years of seniority. ‘Until that happens, the minority population of the union cannot support a strike’” (Kindleberger, Tolbert, and Cooper 1981).

Vice President Ed Doherty read the vote tally: 1404 against striking, to 836 for striking. The hall “erupted in a round of cheers and claps.” But many union members were devastated.

After the no-strike vote, BTU President Kathy Kelley yielded the floor to Paul Nevins, an eleven-year veteran teacher who was laid off, who addressed the membership: ”You have spoken; we have heard the message. We will leave, but we will not go away … you have voted with your voice to execute this union. You have no courage, you have no voice, you have no soul … ” (Article by Tom Roach, BTU Oct. 1981 Issue)

UPI reported, “After the vote, some teachers wept openly and others burned their membership cards to express their anger… Some of the teachers – many of whom were among 1,000 fired over the summer– formed a double row at the exit of the Commonwealth Pier hall where the vote was taken and chanted ‘You’re next, you’re next’ as other members were forced to walk between them” (Anon 1981).

Forty years later, black educators still had painfully vivid memories of the moment they left the meeting. As Barbara Fields recounted:

“I remember at the end of the meeting, walking out of the union hall, and there were white teachers on each side. We’re walking down the middle. I guess maybe people were coming out of rows, so everybody was facing the middle so it looked like you’re walking down a line of very angry white teachers, who were very upset because they felt like they were losing their jobs and we were keeping ours. So that’s when I experienced a whole lot of tension” (Fields 2021).

Bob Marshall described the same harrowing event,

“I’ll never forget, they had these partitions… And they formed a line. You had to walk – it was like a gauntlet you had to walk through that to get to the parking lot. And we were called scabs, niggers, it was ugly. I will never forget that. So for a long time, there was a schism between Black teachers and the administrative staff at the BTU. It was ugly. And because every time the union would go into court and hire lawyers to try to do away with affirmative action and other issues like that around hiring, and then layoffs, you just alienated more Black teachers. It was unbelievable.” (Marshall 2021).

A strike had been averted, but at a huge cost to union identity and sense of unity. The wounds of that day felt raw and real, and the impacts reverberated.

The Strike in the BTU Union Newspaper

The October 1981 issue of the Boston Union Teacher reflected a deeply and tumultuously divided union. While there was some attempt to portray even-handedly the events of the past month, the reporting in the union’s own newspaper came down firmly on the side of the fired 710 teachers.

The issue opens with Kathy Kelley’s exhortation to keep fighting “not only for teacher unionism, but also for teacher professionalism,” a phrase that could be heard as coming down on the side of supporting more experienced, white, “professional” teachers, rather than the later-hired and less-experienced Black and minority teachers.

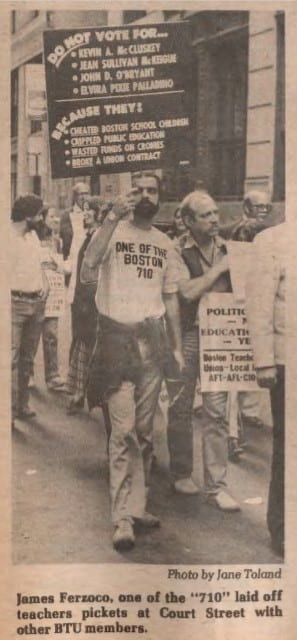

The front page includes a photo of Kathy Kelley addressing the laid-off teachers during the Court St. demonstration which led to several arrests for disorderly conduct, and another photo of laid-off teacher James Ferzoco, marching with the picketers at Court St., wearing a t-shirt that says “One of the Boston 710.”

The next page is dominated by an open letter sent to The Boston Globe by the Seniority Coalition of the Boston Teachers Union, which advocates against Judge Garrity’s orders and leads off with racially charged language: “The Boston School Committee proposes to lay off over 1000 teachers, most of whom are tenured and white, and to replace them with over 700 provisional teachers that are not tenured but are minorities.”

The open letter goes on to call the Judge’s order “illegal and discriminatory” and to assert that “The concept of seniority is racially neutral and color blind. It is fair and equitable in that it protects the rights of all trade unionists from arbitrary standards when layoffs must occur.”

This framing completely overlooks the basis of Judge Garrity’s initial order, which was the finding that the Boston Public Schools had been discriminating for years against hiring teachers of color. When the basis of “seniority” is an inequitable hiring process, then using seniority alone as the basis of the firing process would inevitably lead to discriminatory outcomes.

The open letter continues by stating: “The threat by the B.S.C. to violate our seniority and job security on the basis of an ‘affirmative action’ quota system is blatantly racist! It violates the rights of all Americans not to be judged on the basis of race. This right is guaranteed by the 14th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.”

This charge of reverse racism is then coupled with a doubling-down of an equation with “experienced” teachers with “white” teachers, thus acknowledging the very problem the Judge’s order was intended to alleviate: “The School Committee’s proposed action to violate the seniority provision of our contract unconstitutionally deprives senior white teachers of their right to earn a livelihood.”

It would be bad enough if this letter were included in a general and balanced debate, holding up both sides of the issue. Remember, the vote not to strike on Sept 20 was nearly evenly divided, with the majority choosing not to strike. But the Oct. 1981 BUT issue is littered with sympathetic language towards the (white) teachers who have been laid off, including an advertisement for a benefit theater performance to support the laid-off teachers, with a sliding scale for employed vs. unemployed teachers: “As a fundraiser, ticket prices are as follows: $15 for employed teachers $10 and $5.50 for unemployed teachers and paras.”

Another article by Paul Nevins, detailing the BTU’s plan to appeal Judge Garrity’s ruling, hammers the point home: “As a consequence of this order, the Boston School Committee in August dismissed over 710 tenured teachers solely on the basis of their race. No tenured black teachers were dismissed.”

It would be hard to be a Black educator in 1981 and feel like the union, and the union paper, was supporting your interests, or even considered you part of the union community.

In a hopeful sign, an editorial by Judith Baker, a teacher who had been laid off after ten years in the Boston Public Schools, instead calls this a “time to sit down and develop a program for unity within the membership.” Baker decries the use of union funds on the appeals process, describing it as “an appalling example of playing upon the moral outrage of white teachers.” Baker stands strong in her support of the affirmative action process, even though she herself had been negatively affected by it:

“I believe that we know that many of these young minority teachers did suffer intense discrimination themselves, because we had many of these people in our own classes in Boston, and personally knew of their difficulties in and out of school. Several outstanding minority teachers in this system were in my classes or those of my immediate colleagues, and many were probably in yours. Without affirmative action, would they have been hired? I doubt it. Are they less able or motivated than we? No.” Among Baker’s suggestions to address the current crises are to “start an ongoing multi-racial task force to deepen the dialogue among our own members.”

Judith Baker’s brief bright spot of reaching for unity and reconciliation is quickly overshadowed by the rest of the issue, however. A photo collage entitled “The BTU Endures a Stormy September” includes photos of the Court St. and City Hall protests, images of BTU President Kathy Kelley in close conversation with members of the BTU “Seniority Coalition,” and images of BTU members burning their union cards after the divisive decision not to move forward with the strike.

Another letter to the editor expresses “Grief and Anger at Layoffs,” while continuations of earlier articles deplore the effects on “the economic livelihoods and professional careers of hundreds of innocent teachers, who were fired solely because of their race.”

In a national context, charges of “reverse racism” were on the rise in the late 1970s, connected to the rise of a conservative backlash to the gains of the Civil Rights movement. The idea that “affirmative action” programs constituted a form of anti-white racism gained traction through the Supreme Court’s decision in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978), which said that racial quotas for minority students were discriminatory toward white people. One of the articles in the 1981 BUT issue specifically references the Bakke case in laying out the possibilities that the BTU could win its appeal against Judge Garrity’s decision.

Overall, the 1981 issue of the Boston Union Teacher puts the union’s challenges and divisions on full display, while still evincing markedly more support for the laid-off white teachers than the minority teachers that Judge Garrity’s order was intended to protect.

Black educators in 1981 felt the chill, and the union’s sense of cohesive solidarity was fractured for years to come.

What Happened Next?

The BTU chose to continue to fight the layoffs in court, in a series of appeals that stretched well into the 1990s. Black BTU educators continued to feel that the union was taking their dues while fighting against their interests in court. Some Black educators tried to secede from the union, but they did not have the support of a large enough group of members to make that viable. Some Black BTU members took the strike vote as a challenge to become more involved in union leadership, so that their voices and interests could not be ignored in the future.

The fiscal crisis and layoffs of 1981 surfaced huge tensions and divisions within the union. A fiscal solution acted in the following years to diffuse some of those tensions. Fairly swiftly in the following years of 1983-1984, Governor Micheal Dukakis’s “Massachusetts Miracle” occurred, a burst of economic growth largely centered in the finance and burgeoning high-tech industries. The East Coast corollary of Silicon Valley, the rise of industries along Route 128 reflected a shift to the generally sunny economic outlook of the 1980s. This infusion of capital helped to partially offset the damaging effects of Proposition 2 ½, and Massachusetts unemployment rates plummeted from a high of 12% in 1975 to a low of 3% by 1985.

Over time, all of the laid-off teachers who wanted to come back were recalled.

The 710 laid-off teachers, and many others, were all given offers to come back to work, often within a year or two of their initial dismissal. Some had moved on to other districts or careers, but many educators did return to the Boston Public Schools. The stories and emotions of the divided union during that time, however, have lingered into the present day.

“If we could’ve come together…”

Forty years later, teacher Bob Marshall reflected on the potential power that the union could have wielded, and the opportunities that were lost:

“And you know the sad part about it? If we had united, we could’ve forced the powers that be to do something about what was going on. But … we couldn’t come together because of race. And if we’d been able to come together, we probably could’ve went down and bum-rushed the mayor’s office and stuff. But no, they didn’t want to deal with it. And like what’s going on today, you know, nobody wants to deal with race. It’s the elephant or the gorilla or whoever sitting in the room that nobody wants to deal with. (Marshall 2021).

Marshall’s incisive reflection reveals a possibility different from the path the union took. The BTU was so bogged down in its racial divisions that it could not unite and exert its power against the real threat: budget cuts. The union’s division was its defeat.

The union’s response to events of 1981 pitted real, meaningful values against each other: Contract Rights vs. Civil Rights. There were real reasons and motivations for the union’s decision to fight the lay-offs in court. The BTU felt backed into a corner by a combination of Judge Garrity’s order and the deep budget cuts stemming from Prop 2 ½ and declining enrollment, itself in part a product of the desegregation fight and resultant white flight to the suburbs. But Black educators felt deeply betrayed by the BTU’s decision. Black educators still speak emotionally about the effects of the in-person vote, even many years later. The internal fight weakened the union at a time of great structural and financial stressors, limiting the ability to present a united front and advocate for all BTU teachers.

Black educators felt deeply betrayed by the BTU’s decision.

The Way Forward

The BTU took decades to regain a sense of unity and forward direction. The current leadership embraces the difficult past, and doesn’t shy away from telling the stories and hearing the voices of all of its members.

In June 2020, the BTU voted in favor of forming a “Truth and Reconciliation Committee” to address some of the wounds of the past, including the lingering inequities stemming from past BTU decisions. At the same meeting, the union also put forward a resolution committed to “Building an Anti-Racist Union.” In contrast with the divisive politics of the desegregation era, the current BTU is focused on building solidarity with the broader community, and creating wrap-around services and schools that meet the needs of all students and parents.

It is important to acknowledge that “desegregation,” of students and of faculty, is not a static goal but a moving target, and that the fight to ensure equal access to equal educational resources continues into the present day.

But the current BTU has committed to addressing the issues, and, in the wake of Judge Garrity’s 1981 decision, the current teaching corps of the Boston Public Schools is more diverse. The chart below, from the Boston Globe, shows that Boston Public Schools’ teaching corps is more diverse than other communities in Massachusetts, and indeed, more diverse than the average public school across America as a whole.

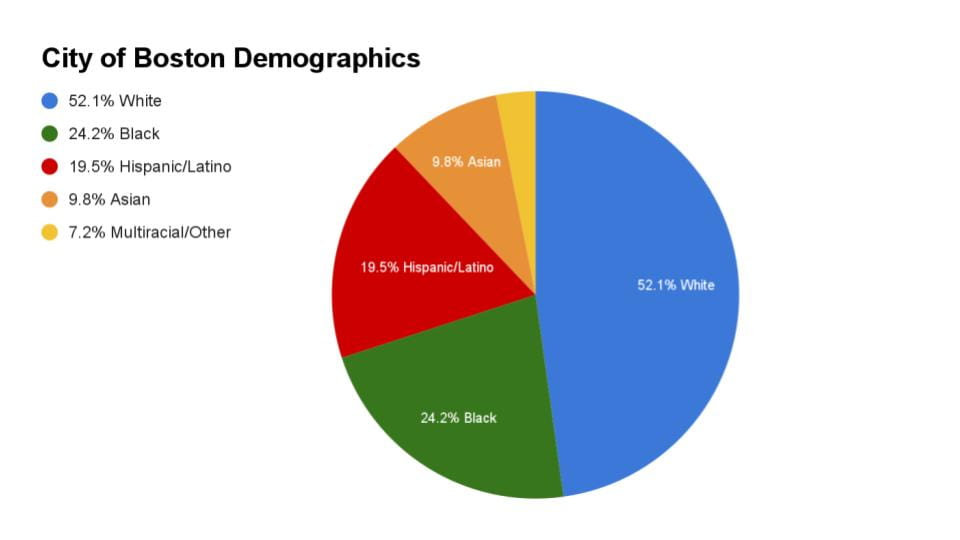

The Boston Public School teaching corps at this juncture, while white educators are slightly over-represented, does generally reflect the overall demographics of the city as a whole.

The way forward actually needs to embrace the new shape of Boston Public School students and families. While the teaching corps maintains a certain proportion of Black educators, roughly reflective of the general population of the city, the largest and fasting-growing segment of students today are Hispanic/Latinx.

To a certain extent, this is an expression of the rapid pace of demographic change and of the amount of time it takes to become a teacher. Often, the last wave of a city’s population ends up teaching the next wave’s children. It is also reflective of the number of students who live in the City of Boston but instead attend charter, parochial, private, homeschool, or other options, including residential programs for students with special needs and the METCO program. Both Black and white students are over-represented in this sub-group of students whose families have opted out of Boston Public Schools.

Clearly, there is still work to be done. But the question, in the end, is was it all worth it? Carmen Pola, a Boston Public Schools parent and member of the BPS Bilingual Master Parent Advisory Council, reflects in a documentary created by the Union of Minority Neighborhoods (UMN) about the lingering impact of the events of 1981:

“The fact that many of our Black professionals could not work in the system until the federal law came, to me, was a very important thing.”

Authored May 3, 2022 by Eleanor Katari and Ari Branz

Ari Branz is currently an organizer at the Boston Teachers Union. They are pursuing a master’s degree in Labor Studies at UMass Amherst.

Eleanor Katari has been a writer, editor, preschool teacher, public school parent, and museum educator. She is currently a Graduate Student in Public History at UMass Boston.