September

The start of the 1974 school year was accompanied by violence in Boston Public Schools. The Boston Union Teacher issue from that month has not been preserved, but there are many accounts of how students, parents, and teachers reacted to desegregation as it unfolded.

Mothers in East Boston warned Judge Garrity that if he ordered their children bussed anywhere else in the city, they would block the tunnel connecting East Boston to downtown. Garrity decided not to test that threat, instead bussing other students into their school.

“Forced busing” became a commonly accepted term used by anti-integration advocates and others to refer to what we now call desegregation. “Forced busing” was a term loaded in nature, using the word “forced” to communicate that some parents were against the practice, and the term “busing” rather than desegregation to focus on the action and not its long-term positive consequence. Today, the term “forced busing” has been replaced with the more inclusive and accurate desegregation.

On September 9, a large “anti-busing” rally was held at City Hall Plaza in downtown Boston. Attendance estimates ranged between 4,000 and 10,000, with protestors largely of Irish descent. School was set to begin later that week, and Garrity’s desegregation plan along with it. Congressman Ted Kennedy, brother of former President John F. Kennedy, arrived at the protest to encourage calm as protestors became increasingly violent. When he walked toward the speaker’s podium, protesters booed and turned their backs to him. “How does it feel to have your right of speech taken away?” one protestor shouted as Kennedy’s microphone was unplugged. “You should be shot, Senator,” another woman screamed.

As Kennedy left the crowd and went inside City Hall, protestors threw eggs and tomatoes at the windows overlooking the plaza. Several smashed a pane of glass near where the Senator was walking. In response, Boston Mayor Kevin White appealed for calm on the city’s major news stations.

These [anti-desegregation] persons and their followers have pushed this city to the edge of disaster, despite the untiring day and night efforts of thousands of city personnel…

-A desegregation supporter writing to the Boston Globe

This picture was taken in the midst of anti-desegregation riots in 1976. While two years later than the 1974 protests, this riot occurred mere blocks from where the 1974 protests took place. (Photo courtesy NPR.)

September 12 was the first day of classes, and South Boston High School was the epicenter of conflict over desegregation. Buses going into South Boston encountered protestors yelling, throwing rocks, and screaming obscenities. Police watched the conflict along the bus route, at times restraining the entirely white crowd. For weeks, this violence continued at South Boston High. Many white students refused to attend a school with Black students, and many Black students feared for their safety. Students of all backgrounds stayed home in large numbers.

October

The Boston Union Teacher‘s October 1974 edition featured an entire page dedicated to status reports of certain schools. In several cases, schools where violence was expected to break out over desegregation witnessed nothing of the sort. Several of these schools, such as Roxbury High and Dorchester High, were in areas populated predominantly by people of color. Only one examined in this issue, Hyde Park High, had garnered a reputation as a site of “volcanic eruption.” The reason for this, wrote teacher B.E. Edelstein, was due to preexisting issues over staffing and poor equipment, not desegregation. That had only exacerbated issues that administrators and teachers were already aware of.

One parent wrote to Garrity that “Integration can only be achieved with open housing – not busing.” Other parents in South Boston echoed their sentiment, leveling accusations of classism at Garrity for living in Wellesley (in the Boston suburbs) but dictating policy in Boston. Though their concerns contained a level of truth, that Garrity’s children did not attend Boston Public Schools, they also communicated racism through their language. “Forced busing,” “forced integration,” and talk of “minorities” as people excluded from the main population of Boston all shed light on the many ways white Bostonians failed to hide their subtle, institutional racism in 1974.

If the recent demonstrations in Boston represent anything, they show how far we must go to achieve reconciliation among our people. For there is no scheme, no plan, no document that will, at a single instant, right all wrongs and satisfy all people.

–October 13 letter from the U.S. Senate regarding desegregation in Boston

November

By November 1974, disputes over desegregation had become so tumultuous that the Boston Union Teacher felt compelled to print an addendum to its usual content:

“We want to share with all members the multitude of ideas present in the Union. Consequently this newspaper, the official organ of the Boston Teachers Union, does not necessarily agree with the content of every article. However, we respect the concept of free speech, and as long as the articles are well written and not detrimental to the well being of the Union, we shall print them.”

Boston Union Teacher, November 1974

The extended abnormality and shock of desegregation was also, oddly, giving way to a sense of normalcy. One teacher wrote humorous descriptions of the police officers regularly posted near Hyde Park High School – the officers had been reinforced because of a stabbing incident the month prior. Grover Cleveland School in Dorchester, a middle school, had “quietly undergone the transition from a predominantly white to a predominantly black student enrollment.” Since there was no violence to discuss, a teacher wrote, she wished to talk about the poor quality of reading education.

While Boston Public Schools was undergoing historic changes, most of its teachers still attempted to do their jobs as effectively as possible.

December

By December, Boston was solidly able to examine how desegregation was affecting its schools. In the Boston Union Teacher, John Doherty, BTU President, outlined “The Boston Plan,” a method by which the BTU hoped to implement desegregationist policies in the city without the need to bus students to different schools.

“The Boston Plan” recommended that in order to desegregate Boston, federal lawmakers use the city as a test site for broader public programs in three specific ways:

- “Establish a team of experts who are knowledgable in all aspects of urban problems…”

- “Designate Boston as a pilot city” for a set of national programs to improve urban areas

- “Implement the recommendations” that the above experts recommend

Doherty and the BTU made good points that desegregation efforts through busing were impacting their ability to optimally educate children. “Busing” was not a perfect solution by any means. Joan Buckley wrote in the Union Teacher that “a simple numerical balancing” could not fix the many problems in the schools such as outdated equipment and poor facilities. She was absolutely correct that funding, allocation, and prioritization of education were essential to the future of the public schools. Those issues still permeate discussions in Boston Public Schools today.

Desegregation and the accompanying conflict did not end in 1974. In many ways its legacy is still present in Boston today. Still, many Bostonians and many teachers recognized the greater good of desegregation. It may have been difficult at the time, but that cost was furthering Civil Rights for all students for generations to come.

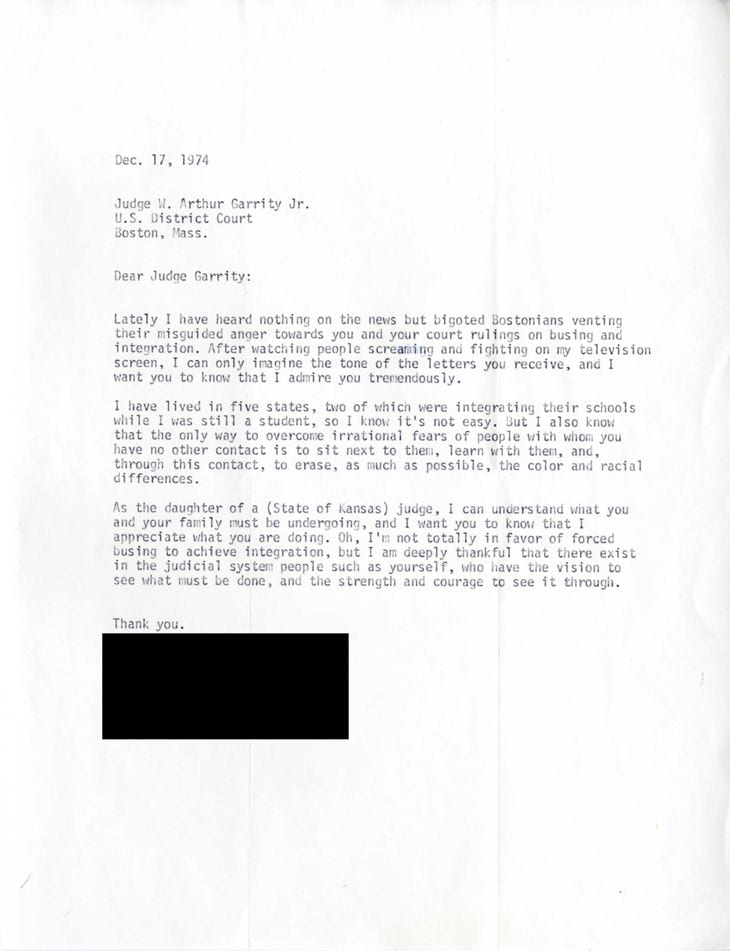

I have lived in five states, two of which were integrating their schools while I was still a student, so I know it’s not easy. But I also know the only way to overcome irrational fears of people with whom you have no other contact is to sit next to them, learn with them…”

Letter to Judge W. Arthur Garrity on December 17, 1974, three months after the initial implementation of desegregation in Boston.