1980.

Boston is still seeing the effects of Judge Garrity’s court-ordered busing and desegregation. Recent decisions on Affirmative Action demand that changes be made to the hiring practices in Boston Public Schools, directly conflicting with Union fights to save tenured teachers’ jobs and honor the protections that come with seniority encoded in the Union contracts. The Boston School Department has gained a reputation for being ineffective, subjecting it to heavy criticism from both City Hall and the BTU.

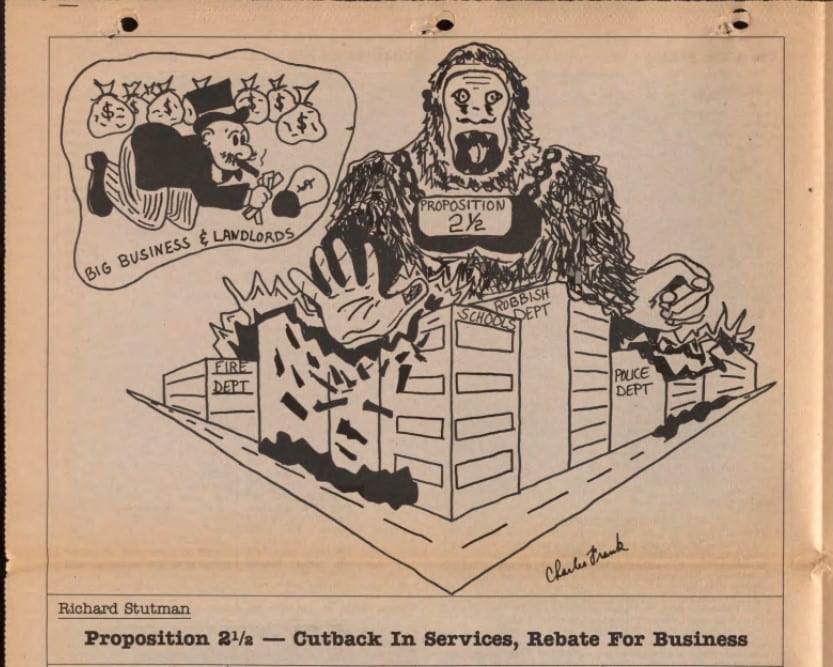

A climate of smaller government, of tax and budget cuts to force efficiency, is sweeping across parties and states. California’s Prop 13, a referendum to slash property taxes, woos Massachusetts voters into creating a copy-cat measure. Massachusetts Prop 2 1/2, initiated by conservative anti-tax group Citizens for Limited Taxation, wins in a ballot measure on November 4, 1980.

By this point, the BTU is battling with Mayor Kevin White to approve the new BTU contract, update the tax code, and accept a budget increase from $195 million to $242 million. Although the courts have ruled in favor of the BTU eight times by November, White appeals every decision, in the hope of procrastinating long enough for Prop 2 1/2 to pass, essentially hamstringing both the Boston School Department and the BTU. Mayor White finally vetoes the council action approving the money for the BTU contract, forcing the BTU to take him back to court. In the midst of all this, Boston School Bus drivers go on strike. Boston schools are facing imminent shutdowns by spring if the contract and budget are not approved.

Before Prop 2 1/2 passed, civil servants and BTU members warned of the detrimental effects a tax cut would mean for budgets across municipalities. The full extent of the disaster was not yet realized in California and politicians there were still touting a victory for the landmark referendum. Meanwhile, states across the country were developing their own versions of property-tax-slashing measures to court voters.

The BTU Calls for Action of Its Members

Massachusetts Prop 2 1/2 was a binding referendum that rolled back local property taxes to 2.5% of assessed value and limited future tax increases to the 2.5% cap regardless of the rate of inflation. This meant that most Massachusetts communities had to reduce budgets by at least 30%. Wealthy communities were relatively unhurt, but poor municipalities, ones that relied more on civil services with an already low assessed property value, would feel the most pressure. Boston, New Bedford, Fall River and Chelsea were hit the hardest, but none were unaffected. Municipalities were forced to close the budget gap immediately despite the measure not going into effect until 1982. In his article in the July 1980 issue of the Boston Union Teacher, Stutman warned of what the realities of Prop 2 1/2 would look like.

“Quincy had to decide whether to close 8 schools or to lay off 125 teachers. Cambridge and Somerville face the same dilemma. Boston exhausted its library budget a month early. Under Prop 2 1/2 these problems would become commonplace.”

Prop 2 1/2 Goes Into Effect

- 351 cities and towns forced to lower property taxes by 15% a year to 2.5% of market value

- Fiscal autonomy for school committees and binding arbitration abolished

- Tax cut weighted against renters

- Older, poorer cities, tending to have the highest property taxes, suffer most

- Cambridge loses 1/3 of its annual budget, laying off 1/3 of its police and firefighters, more than 1/3 of teachers and public works employees

- Health care centers, libraries, and community schools close

Effects Seen in Boston

“Boston will be the hardest hit. It has a large low-income population that depends on the city for services, but its property tax base is riddled with tax-exempt universities, churches and government agencies”

Class Struggle Beyond Unionism: Boston-Area Public Workers’ Ferment. 1981-1982

- April 1981: Boston schools run out of money and stay open only when ordered by courts

- Mayor White closes several neighborhood police stations and 13 fire stations

- Sit-ins and demonstrations attract national attention

- Property taxes cut by $600 million by 1982, down by $1.3 billion after 3 years

- In an effort to deal with the new budget, White and the School Department start closing schools

- 13 schools close in the first year, Judge Garrity says it will assist in desegregation

- 28 schools slated to close by 1982

As Schools Continue to Close, Kathleen Kelley Raises the Alarm. Mayor Kevin White Accepts the Challenge

Shortly after the passage of Prop 2 1/2, Boston schools, serving 65,000 students, begin to face system-wide school closures by early February. The Mayor had designated only $195 million in the 1980-81 budget, the same as the budget for 1979-80 and the lowest possible funding allowed under state law. The BTU had negotiated for a $15 million increase since August. Not only were teachers working under the previous year’s wages, the schools were operating over budget, having not received the needed increase to $242 million. The schools required the extra money in part to fund the state-mandated special needs programs and accommodations for students with physical, emotional, or academic handicaps.

“The Mayor justifies his position on the basis of trying to force the school board to trim from its budget what he sees as fat.”

Christian Science Monitor, Feb 10, 1981

“Boston, which opened the nation’s first public school system more than 150 years ago, may become the nation’s first financially distressed major city to involuntarily close schools because of a shortage of money.”

While Garrity pressured schools to integrate, 27 schools closed, due to a combination of budget issues and attempts to create more racially-balanced public schools. The BTU opposed the closures, partially as it would eliminate services for students and partially because it meant the firing of 710 tenured white teachers. The BTU responded bitterly to the court orders protecting affirmative action, which circumvented Union policies of seniority.

“Demands by black parents that schools remain open, strike or no, and that black teachers report to class regardless of union action.”

For Boston Public Schools It’s Showdown Time Again, Christian Science Monitor, Sept 18, 1981

No one came out on top. Garrity’s court orders to uphold protections for students and teachers of color were poorly implemented, as were the mandates for special needs accommodations for students and the hiring of people with disabilities. Mayor White, seizing the opportunity, created a stranglehold on the BTU and Boston School Department. The Boston School Department was forced to close schools, but refused to “trim the fat” at Court St, preserving funding for school administration while classrooms and teachers suffered. Courts upheld the BTU contract, but White appealed and circumvented the court orders at every turn. The BTU privileged striking to preserve jobs for tenured white teachers, while it deprioritized protections for provisional Black and Latinx teachers, who remained underpaid and often holding the reins in underfunded and overcrowded and newly integrated classrooms. The bitter fight created deep divisions, which damaged union solidarity and effectiveness for decades to come. System-wide school closings because of contract fights hurt students the most, and the reputation of the Boston Public Schools, and the city as a whole, suffered. This feels like a fight that nobody won.