The Boston Teachers Union has a storied history in the city of Boston and in United States labor history. The organization has fought for collective bargaining rights, higher pay, and better working conditions for Boston’s teachers for decades. However, progress does not absolve the union from imperfections. One of the darkest stains on the BTU’s history was its organizational reaction to court-ordered desegregation – sometimes referred to as “busing” – in Boston’s public schools. Desegregation divided teachers and led to immense outpourings of violence, all in the historic pursuit of greater equality for educators and students. Extensive books could be, and have been, written on this topic, so this blog post only scratches the surface.

It is important to note that in the years since, the BTU has taken action to remember its legacy, both good and bad. In 2020 the union passed a resolution calling for “Building an Anti-Racist Union,” which included plans for an internal Truth and Reconciliation Committee to investigate its role in desegregation. The 50th anniversary of desegregation is fast approaching, which makes this a critical time to examine complicated histories. The BTU is already planning efforts to remember desegregation officially in 2024. While histories like desegregation are painful for many people in Boston, it is vital that we shed light on them. Honest truths are difficult to face, but they are part of the path to healing.

What Was Desegregation?

In 1974, Judge W. Arthur Garrity of the United States District Court ruled in Morgan v. Hennigan that all children in Boston were entitled to “a quality integrated education for every student in the city.” In schools where the student body was over 50% white, integration would need to take place in some form to even out the racial makeup of the student body. His ruling upset the status quo that existed at the time – a segregated school system, split by historical divisions of race and class throughout Boston. Garrity’s ruling made clear that Boston Public Schools had been unconstitutionally segregating its students until that point, and as a result, practices would need to change drastically.

These changes were implemented through a practice known as desegregation, sometimes called “busing,” “forced busing,” or “forced desegregation.” Students would take a bus to schools outside of their own district, often to areas predominantly occupied by people of a different race than themselves. Similarly, Judge Garrity also ruled that Boston Public Schools needed to hire more Black teachers to combat the de-facto segregation being perpetrated by an imbalance of white instructors teaching Black students.

Public reaction to both of these efforts was swift. The November 1974 edition of the Boston Union Teacher reported that there were “four teachers out of school with broken limbs and one with a ruptured disk,” as well as thirty cases of assault carried out against educators in the first three months of school alone. In the entire previous school year, there had been only sixty-five similar cases. The most affected neighborhoods were traditionally working class white neighborhoods, such as South Boston, and historically black neighborhoods, like Roxbury. In 1974, after the desegregation ruling, Roxbury High had an assigned enrollment of 550 white students and 400 students of color. When the school opened that fall, 214 students of color enrolled. Only 20 white students, by contrast, had enrolled. The majority of white students set to begin classes at Roxbury High were coming from South Boston, one of the main locations where protests against desegregation occurred.

Reactions Within the BTU

Teachers had mixed responses to Judge Garrity’s decision. Quite directly, BTU President John Doherty wrote in the Boston Union Teacher that “many teachers personally disagreed with the remedies initiated by the desegregation order.” The BTU also organizationally denounced Garrity’s decision. Desegregation efforts, dissidents claimed, negatively affected teachers’ ability to connect with students, communicate with families, and effectively teach in contested districts. The Boston Union Teacher tends to reflect this view.

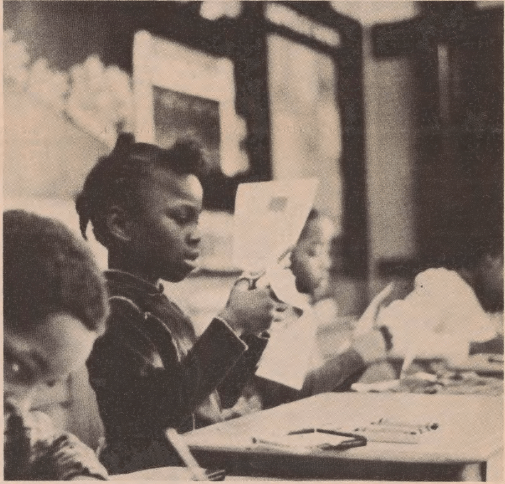

Black students and teachers, meanwhile, felt as though they had to fight for an education. In some cases, Black students were afraid to attend schools which had previously been predominantly white for fear of retaliation by white students and parents. Their fears were perfectly logical – the instances of violence described above are proof of that.

The Use of Language

Take note of the way many issues of the Boston Union Teacher written around this time refer to desegregation as “forced busing.” The use of language is subtle, but notable. Similarly, a December 1974 issue of the Boston Union Teacher uses the word “ghetto” to describe a Chicago school located in an underserved area of the city. The heroic teacher being depicted in this book review seems to civilize the poor students he educates, and shows them how to live a successful life upon his arrival at the school. An editorial on violence in early 1976 at Hyde Park High School surmises that the result of Brown v. Board of Education was that schools began to be treated like “laboratories for curing this social problem.”

This language was not meant to be harmful – but it was. In the same way, the BTU’s historical opposition to desegregation was not meant to be racist. That does not remove the discriminatory implications from its language. In examining the history and legacy of the BTU, it is inevitable that we will find parts of it that do not reflect well on the organization or on Boston itself. However, the BTU has grown from this episode in its history. Today, its members advocate for racial equality in education. Its President is a woman of color. In the failings of the past, the BTU has found ways to move forward more equitably in the present.