Being a woman in the American workplace, especially prior to the twenty-first century, often means association with education. That’s certainly no exception for my family. My mother was a teacher’s aide for kindergarten classes. Two of my aunts are teachers. My maternal grandmother worked in administration, and my paternal grandmother was a school crossing guard. Most recently, my sister left an early education center for an elementary classroom of her own. Their careers taught me at a young age how much the education system relies on these women to not only nurture young minds, but to be the pillars of the system’s daily function as well.

However, I also recall my mother being underpaid for working in a classroom, the lunchroom, playground, and bus duty every week. Women are arguably the backbone of the education system, certainly within elementary and middle schools, yet they have historically been underrepresented and underpaid within and by administration. The Boston Teachers Union began in 1945, formed by women in education, but they didn’t have their first female president until 1979, when Kathleen Kelley won the position. Kelley was president for only four years, stepping down in 1983. The BTU didn’t see another woman lead until 2017, when Jessica Tang became the second ever female president and the first ever person of color to hold the position.

The vast majority of public school teachers and paraprofessionals in the United States historically were women, a trend that continues. Despite their prominent roles, their voices have been repeatedly suppressed by male leadership in organizations like the BTU and in publications like the Boston Union Teacher. Paraprofessionals, especially teacher’s aides, fought tirelessly for better pay, better protections, and better representation.

A Woman’s View…

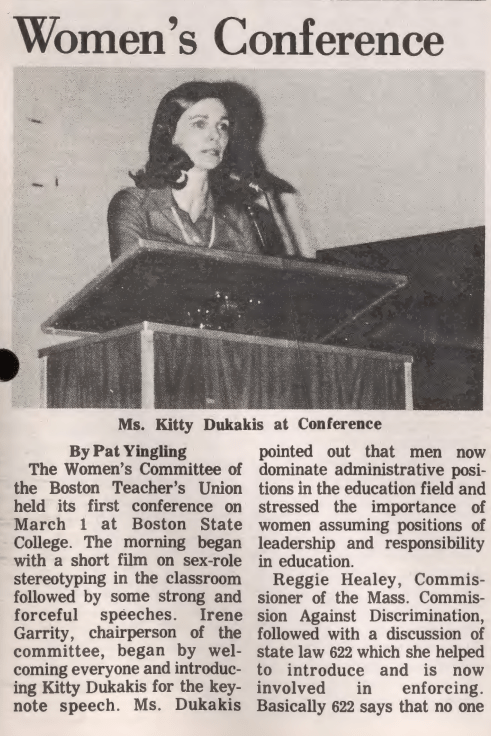

While the primary body of the BTU was dealing with segregation in Boston Public Schools, the Women’s Committee of the Boston Teacher’s Union held their first conference in March of 1975. Their mission was to address the discrimination female teachers faced in the workplace (despite being the majority of the labor force). This included the lack of women in administrative positions, sexist stereotypes in the classroom, and the enforcement of Chapter 622 of the 1971 Massachusetts Legislative Acts. This conference directly confronted the discrimination women faced within the education system.

The events of this conference were written up in the Boston Union Teacher newsletter of that April by Patricia Yingling. What’s truly ironic is the article directly next to it, a similar one detailing the events of the conference and the major points made. It is much shorter and does expand a bit more on the workshops that were held, but overall reiterates the same points the main article made. The difference? It was written by a man and titled “A Man’s View…A Single Step.” Overall, this smaller article offered very little distinctive substance from the one written by Yingling, so was it published simply to have a man’s opinion on the subject?

Overworked and Underpaid

The previous year in BTU history brought me back to my own experiences as a girl in my family. In 1974, the Boston Union Teacher followed the story of Boston Public Schools teacher’s aides, who were cooperating with the BTU to negotiate better contracts, which included better pay and sick leave. It reminded me deeply of my own mother, who, as a teacher’s aide in Michigan, was severely underpaid for the work she did. She worked inside and outside the classroom, even running an after-school program. Yet she made barely over minimum wage. Unlike the aides of the Boston Public School system, she and the other aides of their school district received no representation from the local teacher’s union.

The vast majority of teacher’s aides are women, and they are often underpaid and overworked. The BTU may have faced many of the discriminatory issues common of twentieth century, but they also provided women in undervalued educational positions a chance at fair treatment by the school system, something that not every district, nor every state, makes available.

The women of the BTU were the backbone of the organization. They formed it in the 1940s. They voted and protested. The Women’s Committee not only stood for the equal treatment of female educators, but they also provided for the organization as through services such as additional childcare. Their stories are distinct from the rest of the BTU’s history, as they advocated for better quality education, better treatment of Boston Public Schools teachers, and for their voice to be heard.