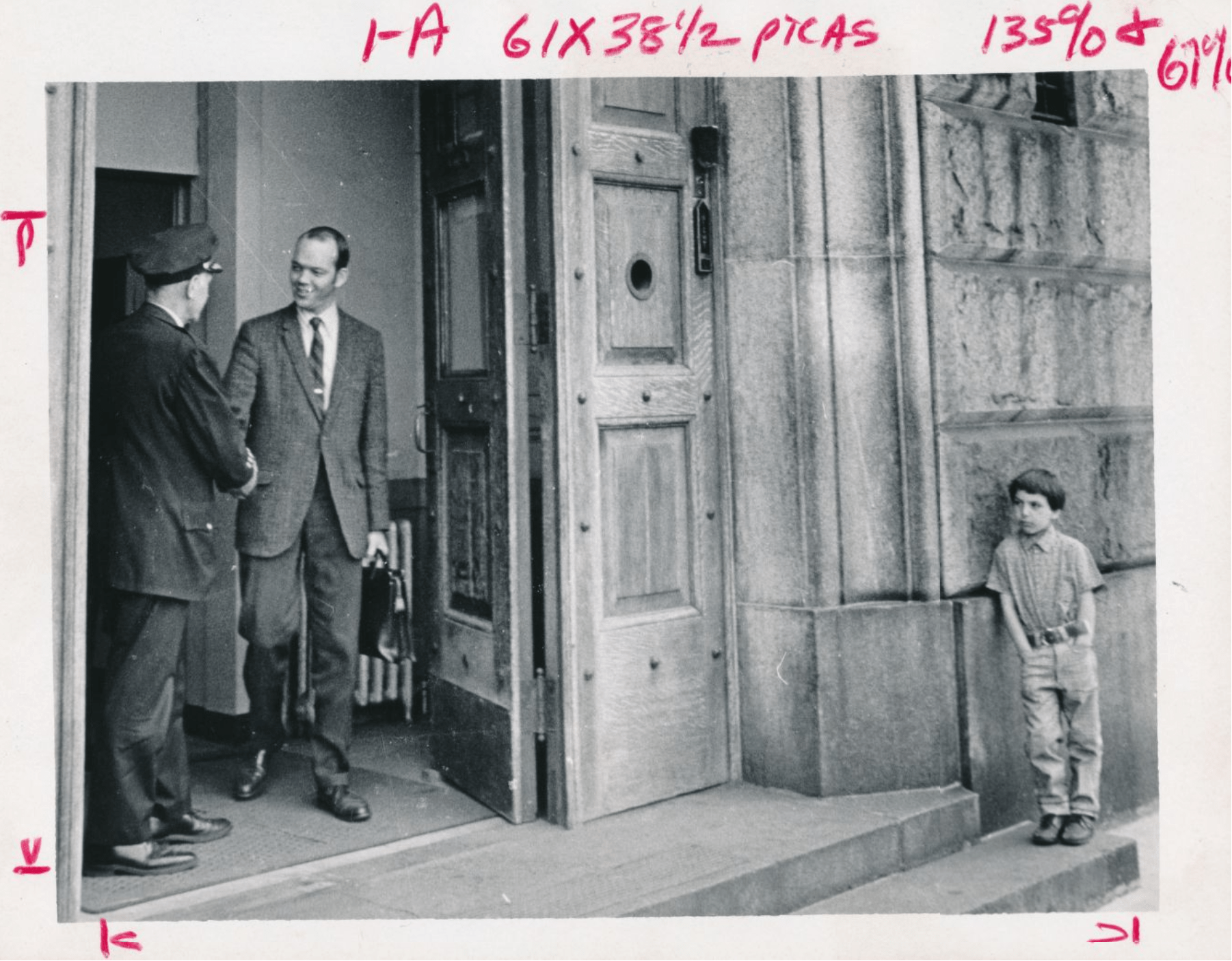

Without its caption, this image might feel ordinary. A man in a suit leaving a sturdy-looking government building stops to shake the hand of the uniformed officer at the door while a child — perhaps waiting for the man — looks on from the steps outside. When we learn that we are witnessing the release of Boston Teachers Union President John Reilly from the Charles Street Jail in May of 1970, however, things get interesting. Why was the president of the city’s teachers union incarcerated? Why does he look so chipper in spite of this fact? Who took this photo, and for what purpose? And who’s the kid?

Teacher Rights and Illegal Strikes

Teachers have organized unions in the United States since the early twentieth century, but teacher unions did not win the right to represent teachers in collective bargaining until the 1960s. Even as states changed their laws to allow public-sector workers to join unions and bargain collectively, however, striking remained illegal. Using rhetoric that traced back to the Boston Police Strike of 1919, politicians across the political spectrum argued that public servants, and particularly teachers, could not be allowed to walk off the job.

Despite this, when newly-elected teacher unionists met School Boards at the bargaining table, they found the bosses had little intention of meeting their demands for smaller class sizes and better pay. When negotiations reached an impasse, teachers called on the tried and true tactics of the labor movement, regardless of the laws on the books. In cities across the country, teachers went on strike in the 1960s, winning new contracts and transforming the work of education in the process.

Since striking teachers were breaking the law, their leaders went to jail. Two months before John Reilly was sent to Charles Street, American Federation of Teachers President David Selden was sentenced to sixty days in New Jersey for walking picket lines in support of the AFT local on strike in Newark. In New York City, United Federation of Teachers President Albert Shanker was jailed after a 1967 strike, and would return to jail one month after Reilly, in June of 1970, to serve time for the UFT’s 1968 strike. When he entered his jail cell, Reilly was in good company among militant teacher unionists.

Public Indignities

The Boston Teachers Union won the right to bargain collectively in 1965 and signed its first contract in 1966. In 1970, however, bargaining broke down as Reilly and his leadership team pushed for bigger gains. After a series of escalating actions, the union went on strike on May 1, the first teachers’ strike in the history of Boston.

Suffolk Superior Court Judge Harry Kalus issued orders for Reilly’s arrest on May 5, in keeping with Massachusetts state law. The following day, the judge issued a no-strike injunction and sent Reilly off to the Charles Street Jail. Reilly would remain there until the strike was resolved on May 19. It was the longest stretch ever served by a Massachusetts labor leader in response to a strike action. In ordering Reilly’s release, Kalus blasted the union’s “illegal strike,” which he described as a “public indignity and a challenge to the authority of this court.” The BTU was also ordered to pay $13,000 in fines for striking.

Picturing the Strike

The Boston Teachers Union has long kept a small collection of photographs from its first strike in 1970. The union digitized these images, including Reilly’s release from Charles Street Jail, in 2018 as part of a BTU Digitizing Day, the results of which are housed online by UMass Boston. While the exact provenance of the photographs is unknown, they seem likely to have been taken for publication in the union’s newspaper, the Boston Union Teacher. The BTU’s archives of its paper have now been digitized, as well, but the collection is incomplete, and a post-strike issue from May or June of 1970 does not survive.

Given the hostility teachers faced for going strike from some members of Boston’s mainstream establishment (including the press), the BTU’s desire to capture its leader in a flattering light is understandable. Reilly’s poise and dress in leaving the jail suggest that he knew he would be photographed, and not just by the BTU’s own photographer. This photo, in particular, seems to have found a use in some BTU publication, based on the markings around its margins. Beyond that, however, questions remain. Was the photo posed, or was it simply a fortuitous shot? Where and how did it appear, and with what accompanying explanations? And who is the child, looking on as a stand-in for the thousands of Boston Public Schools students who might have sought an explanation for their unplanned May vacation?

3 replies on “An Arresting Photograph”

My dad John Reilly says it was not posed.

Hi Maureen,

I was looking up the article on your Dad and saw your comment. Glad you responded. The photo is so your Dad, always a smile and a handshake.

May I add to my comment about John Reilly, a wonderful man loved by all.