(Source: Eliot C. Clarke, Main Drainage Works of the City of Boston, 1888.) (Click to enlarge image)

Boston’s new sewerage system, built in the 1870s and 1880s, was designed to take waste from the city and dispose of it miles away from the local population. The map below shows the newly constructed sewers that drained into the one sewer that led down to the Calf Pasture. Gravity allowed waste to travel from downtown Boston neighborhoods that sat on higher land, to Dorchester’s Calf Pasture on a lower elevation.

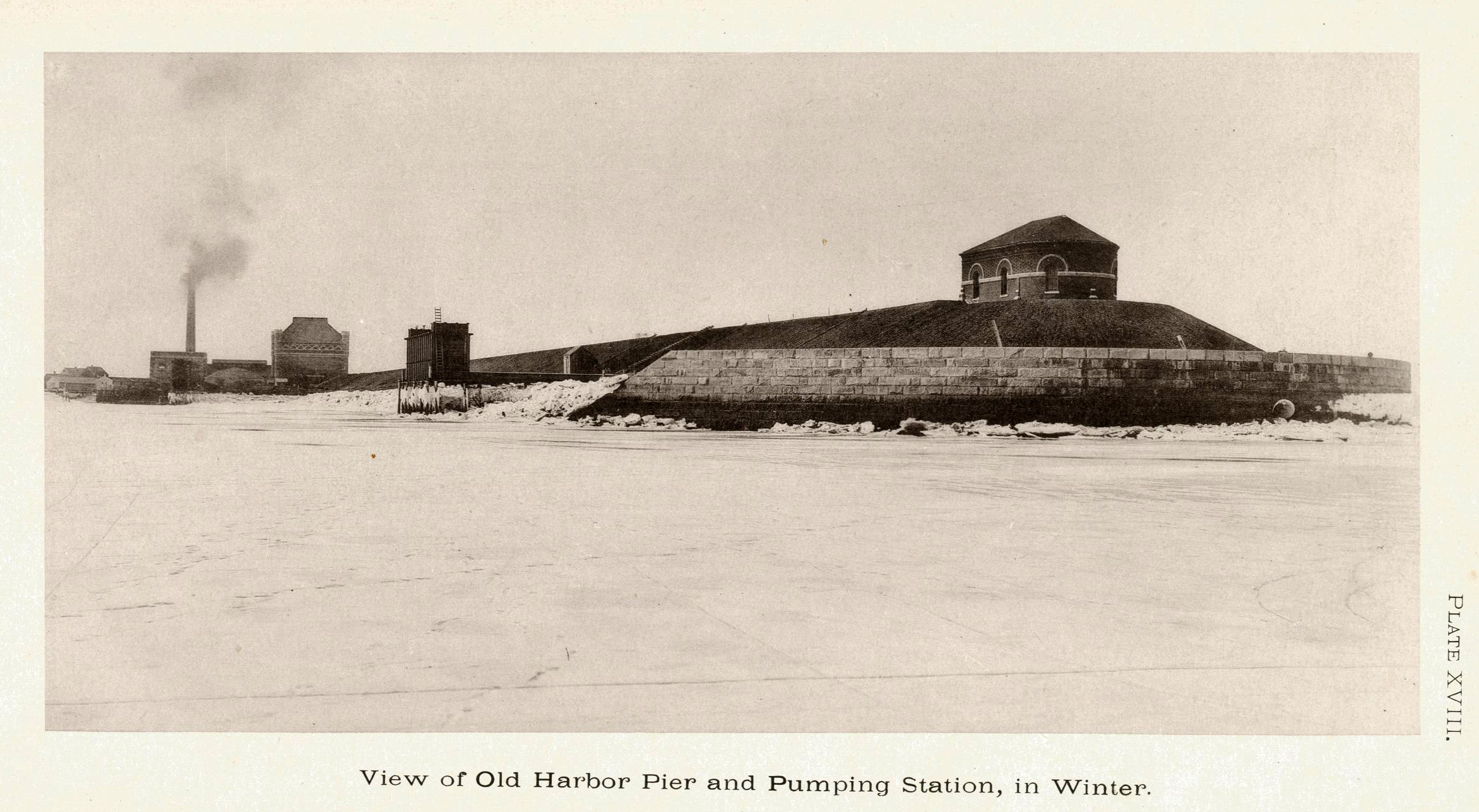

After the sewage reached the Calf Pasture Pumping Station, it still had a great distance to travel before reaching its final destination, Moon Island, west of the peninsula in Quincy Bay. To make the last leg of this journey, the station’s massive pumps lifted the sewage thirty-five feet to enable its journey away from the heavily populated city, past the oscillating tides, towards Moon Island.

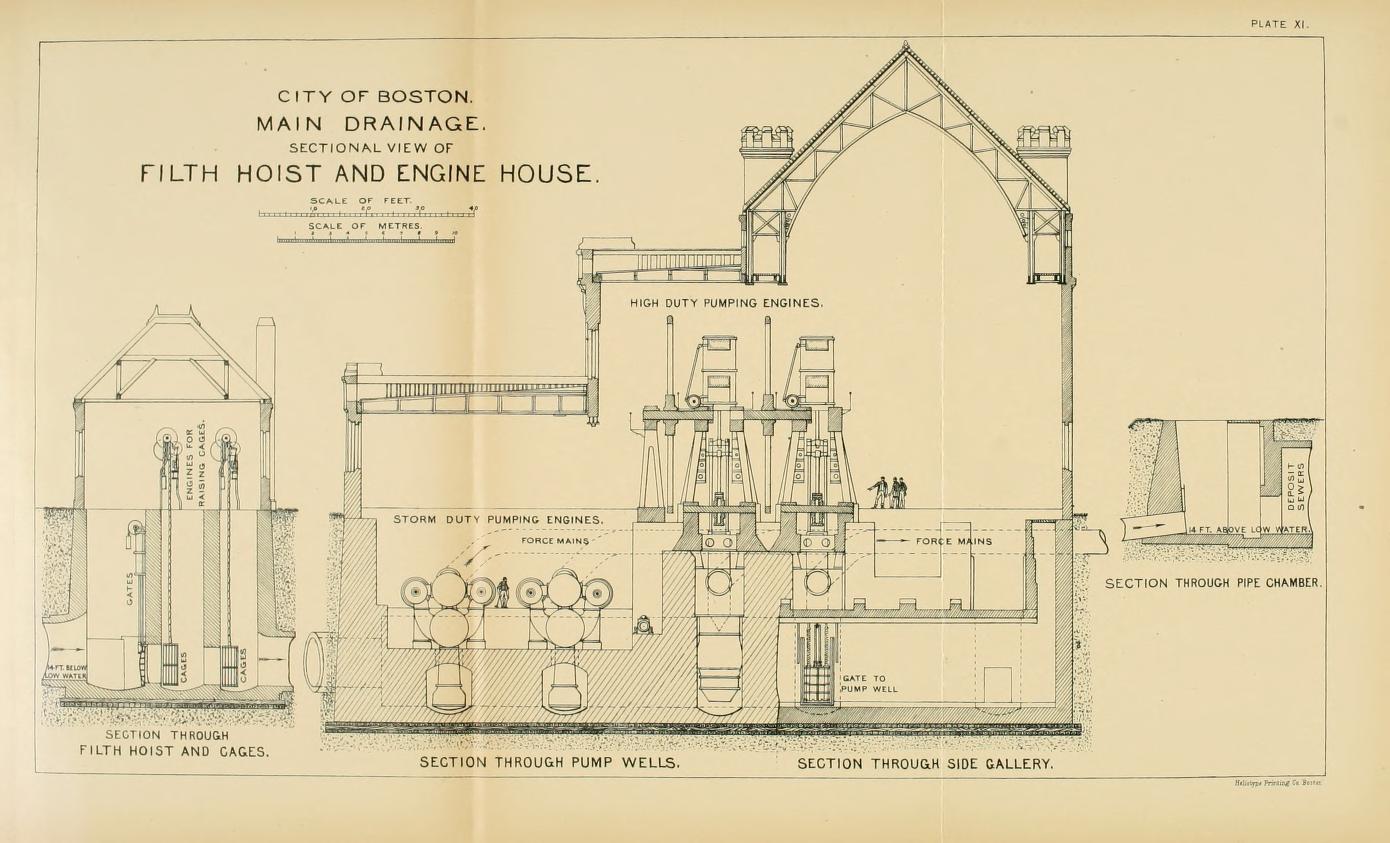

What’s in the pumping station? How does it work? An 1888 blueprint of the building illustrates the various functions of the large building.

The coal house held giant bins to store the coal that created steam power to run the boilers and power the integral pumps. The pumping station was large enough to store 2,500 tons of coal at once, since the pumping station burned over six tons of coal each day. Ships docked nearby on the peninsula to deliver new coal shipments to the pumping station’s elevated coal run.

This huge measure of coal fueled two major Leavitt pumps, which ran continuously throughout the day. Each engine could pump up to 25 million gallons of sewage per day. In the mid-1880s, the two engines pumped an average of just under 37 million gallons each day.

In some cases, excess storm water pushed the pumps to their limits. In preparation for this possibility, the engineers installed two additional emergency pumps. These two smaller storm duty pumping engines were used sparingly, because they were less fuel efficient than the major Leavitt engines. Still, they proved crucial when unexpected amounts of water came through the station.

Sources Consulted:

- “The Boston Sewer System and Main Drainage Works.”Scientific American. no. 28 (1887): 351.

- Clarke, Eliot C. Main Drainage Works of the City of Boston. Boston: Rockwell & Churchill, 1888.

Photo Credits:

- Clarke, Eliot C. Main Drainage Works of the City of Boston. Boston: Rockwell & Churchill, 1888.