Prior to the development of sophisticated sewerage systems like the one that Boston created in the 1870s, urban water supplies posed a significant health risk to residents. Water-borne illnesses such as cholera, dysentery and typhoid thrived in the unsanitary conditions that came with dense urban living before modern sanitation. Between 1846 and 1863, several cholera outbreaks struck India, then the Middle East, then Europe and Africa, before making their way to the United States. Estimates suggest that these outbreaks resulted in a total of over one million deaths .

In the large towns of colonial America during the 17th century, the earliest residents often had a privy at ground level that discharged directly into the street, usually with an open gutter or channel serving as a sewer. Occasionally, privies led to cesspools or vaults which stored the waste until it could be disposed of or until it soaked into the ground. Often, however, waste remained in the streets, in contact with food and water sources, wandering livestock and human feet. By the 19th century, many urban areas had adopted a dry sewerage system in which residents transported the contents of their privies to a designated area in order to try and stave off widespread contamination.

King Cholera

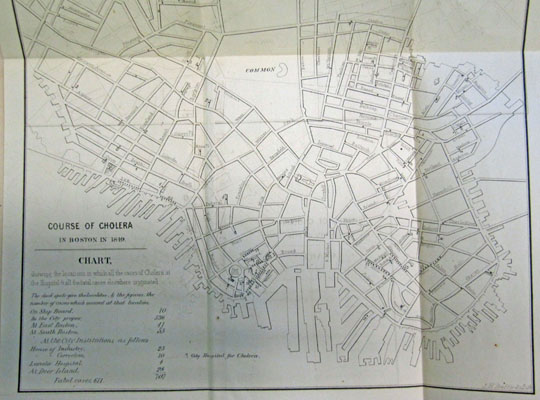

In 1848, over three hundred Italian immigrants who had been exposed to the cholera virus arrived by ship in New York City. Although there were some attempts at quarantine, the city had not seen an cholera outbreak in fifteen years and was unable to contain the virus. Within months, the cholera pathogens spread from New York City to Boston. The disease spread rapidly through the newly crowded cities, sending residents and public officials into a panic.

In Boston, the mayor issued a public announcement advising people to practice hygiene and instructing them to collect waste and rubbish on particular days so that the city could systematically dispose of it. Newspapers published articles on the symptoms of cholera and treatments for it. Nonetheless, the toll taken on the city was significant.

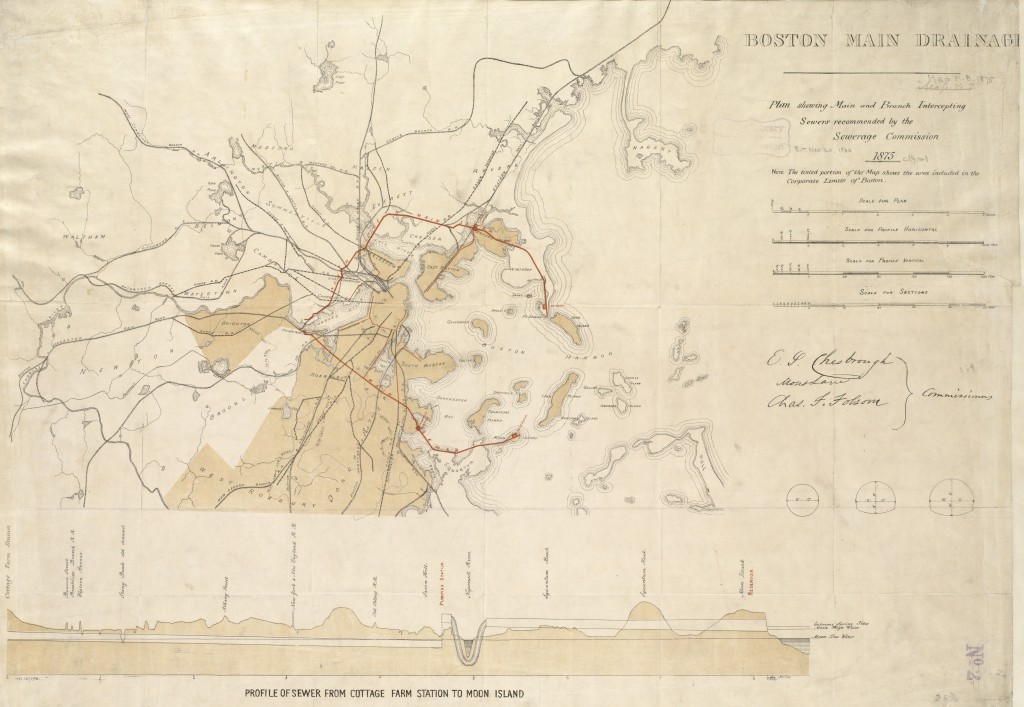

After the outbreak of 1849, and the following outbreak of 1866, Boston began to look towards an overhaul of the sewerage system to modernize the city and protect its residents from disease. By 1875, Boston had launched a study to research pollution and water contamination causing health issues including cholera, typhoid and dysentery. The study prompted a newly designed sanitation system, which was completed and functional by 1884; this system included the Calf Pasture Pumping Station Complex, and the Moon Island treatment facility. This investment in public health had a huge impact on curtailing the spread of waterborne diseases in the city and brought Boston into the modern age of sanitation.

Sources Consulted:

- Burian, Steven, Stephan J. Nix, Robert E. Pitt, and S. Rocky Durrans. “Urban Wastewater Management in the United States: Past, Present, and Future.”Journal of Urban Technology. no. 3 (2000): 33-62.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Cholera-Vibrio Cholerae Infection .” Last modified 5 21, 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/cholera/prevention.html.

- Rosenburg, Charles. The Cholera Years: The United States in 1832, 1849, and 1866. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Photo Credits:

- Cholera Map – http://www.historyofvaccines.org/content/cholera-boston-1849

- “King Cholera” – http://www.victorianweb.org/science/health/cholera.html

- Cholera Announcement – http://www.flickr.com/photos/cityofbostonarchives/4479753024/in/photostream/