The Histories of the Calf Pasture Pumping Station Blog began in 2013 as the result of a practicum project by UMass Boston public history graduate students. Under the direction of Dr. Jane Becker, they worked in partnership with the University Archives & Special Collections to research the rich history of the Calf Pasture Pumping Station.

The blog was updated in 2016 to continue to raise awareness and educate the public about the Calf Pasture Pumping Station, and to encourage the UMass Boston community to look towards the future of the preservation of the important historic structure.

Since its closure as an active pumping station in the late 1960s, the Calf Pasture Pumping Station has been neglected. Currently, most windows are boarded up and a high fence surrounds the property as the various institutions on Columbia Point build and expand. The beauty of the building and the mystery of the inaccessible have led many people to wonder what the interior looks like.

UMass Boston’s Associate Provost Peter Langer toured the inside of the building in 2011, and took these photographs.

Several others have had access to the building, and recorded the building’s interior. Late in 2008, an artist entered the building, and documented their visit on the website Desolate Metropolis.

Have you been inside the Calf Pasture Pumping Station? Do you have observations or pictures? Please share these with us in the comments section below. in the comments below?

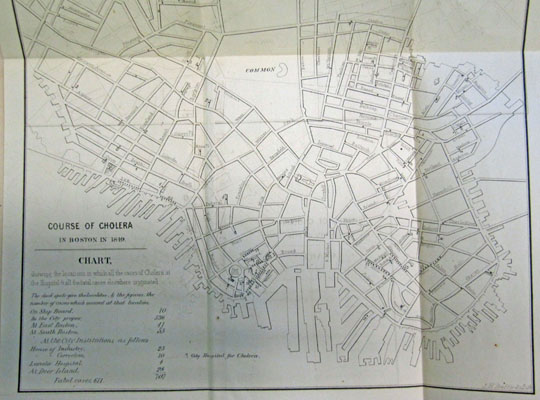

Prior to the development of sophisticated sewerage systems like the one that Boston created in the 1870s, urban water supplies posed a significant health risk to residents. Water-borne illnesses such as cholera, dysentery and typhoid thrived in the unsanitary conditions that came with dense urban living before modern sanitation. Between 1846 and 1863, several cholera outbreaks struck India, then the Middle East, then Europe and Africa, before making their way to the United States. Estimates suggest that these outbreaks resulted in a total of over one million deaths .

In the large towns of colonial America during the 17th century, the earliest residents often had a privy at ground level that discharged directly into the street, usually with an open gutter or channel serving as a sewer. Occasionally, privies led to cesspools or vaults which stored the waste until it could be disposed of or until it soaked into the ground. Often, however, waste remained in the streets, in contact with food and water sources, wandering livestock and human feet. By the 19th century, many urban areas had adopted a dry sewerage system in which residents transported the contents of their privies to a designated area in order to try and stave off widespread contamination.

King Cholera

In 1848, over three hundred Italian immigrants who had been exposed to the cholera virus arrived by ship in New York City. Although there were some attempts at quarantine, the city had not seen an cholera outbreak in fifteen years and was unable to contain the virus. Within months, the cholera pathogens spread from New York City to Boston. The disease spread rapidly through the newly crowded cities, sending residents and public officials into a panic.

In Boston, the mayor issued a public announcement advising people to practice hygiene and instructing them to collect waste and rubbish on particular days so that the city could systematically dispose of it. Newspapers published articles on the symptoms of cholera and treatments for it. Nonetheless, the toll taken on the city was significant.

After the outbreak of 1849, and the following outbreak of 1866, Boston began to look towards an overhaul of the sewerage system to modernize the city and protect its residents from disease. By 1875, Boston had launched a study to research pollution and water contamination causing health issues including cholera, typhoid and dysentery. The study prompted a newly designed sanitation system, which was completed and functional by 1884; this system included the Calf Pasture Pumping Station Complex, and the Moon Island treatment facility. This investment in public health had a huge impact on curtailing the spread of waterborne diseases in the city and brought Boston into the modern age of sanitation.

Sources Consulted:

Photo Credits:

As Boston grew and its residents learned the dangers of pollution, they understood the problems resulting from the release of sewage into the harbor at Moon Island. Bostonians called for a cleaner harbor, and by the 1960s and 1970s treatment of sewage was rerouted to Deer Island.

But the Boston Water and Sewer Commission still used the Calf Pasture Pumping Station on occasion. In the 1970s, during heavy rains, excess street water was channeled to the pumping station, where it was treated behind the station, on the side of the building that faces the UMass Boston campus. Eager to end such use on their campus, in 1999, university administration began negotiations to purchase the property.

The Boston Water and Sewer Commission was reluctant to give up the Calf Pasture Pumping Station, because they would have to build a new facility somewhere else in the Boston area. Local politicians took up the debate. After a dozen years, in 2012 the university finally reached an agreement with the city and the Boston Water and Sewer Commission, and purchased the pumping station.

What is the future of the Calf Pasture Pumping Station at the University of Massachusetts Boston? How can it be used? Many faculty members and administrators have made suggestions for possible re-use of the building. There are many challenges to conquer before renovation can occur. These include environmental remediation at the site, and completing a structural report to assess the work needed to reuse the space.

Recently the University released a large twenty-five-year plan for renovations to the UMass Boston campus, but the pumping station is not included in this plan. The university did not yet own either the Calf Pasture Pumping Station or the Bayside Expo Center in 2007, when the 25 Year Master Plan was unveiled

Today, major redesign of the UMass Boston campus and the construction of new buildings and roadways are underway. In the new design, a new street will bring visitors in front of the majestic Calf Pasture Pumping Station, though its future use remains uncertain.

At present, boarded up windows and fencing secure the pumping station against general access. At the front of the building, construction of a new roadway has commenced, and the university prepares to build its first residential complex near the site.

Rehabilitation, preservation and reuse of the Calf Pasture Pumping Station will require great financial resources as well as vision. This historic structure, its historical and architectural significance documented by a National Historic Register nomination, remains at risk. The physical condition of the building continues to deteriorate, as local development and the need for space put additional pressure on this historic site.

The Calf Pasture Pumping Station provides us with access to multiple stories of the past that have relevance to the present. It engages histories of technology, architecture, public works, public health, labor, environment, neighborhood, housing, and politics.

What ideas do you have for bringing these histories into the present, for the benefit of Boston’s citizens? What histories matter to you?

View Calf Pasture Pumping Station in a larger map

This map shows sites related to the Calf Pasture Pumping Station, including:

Moon Island

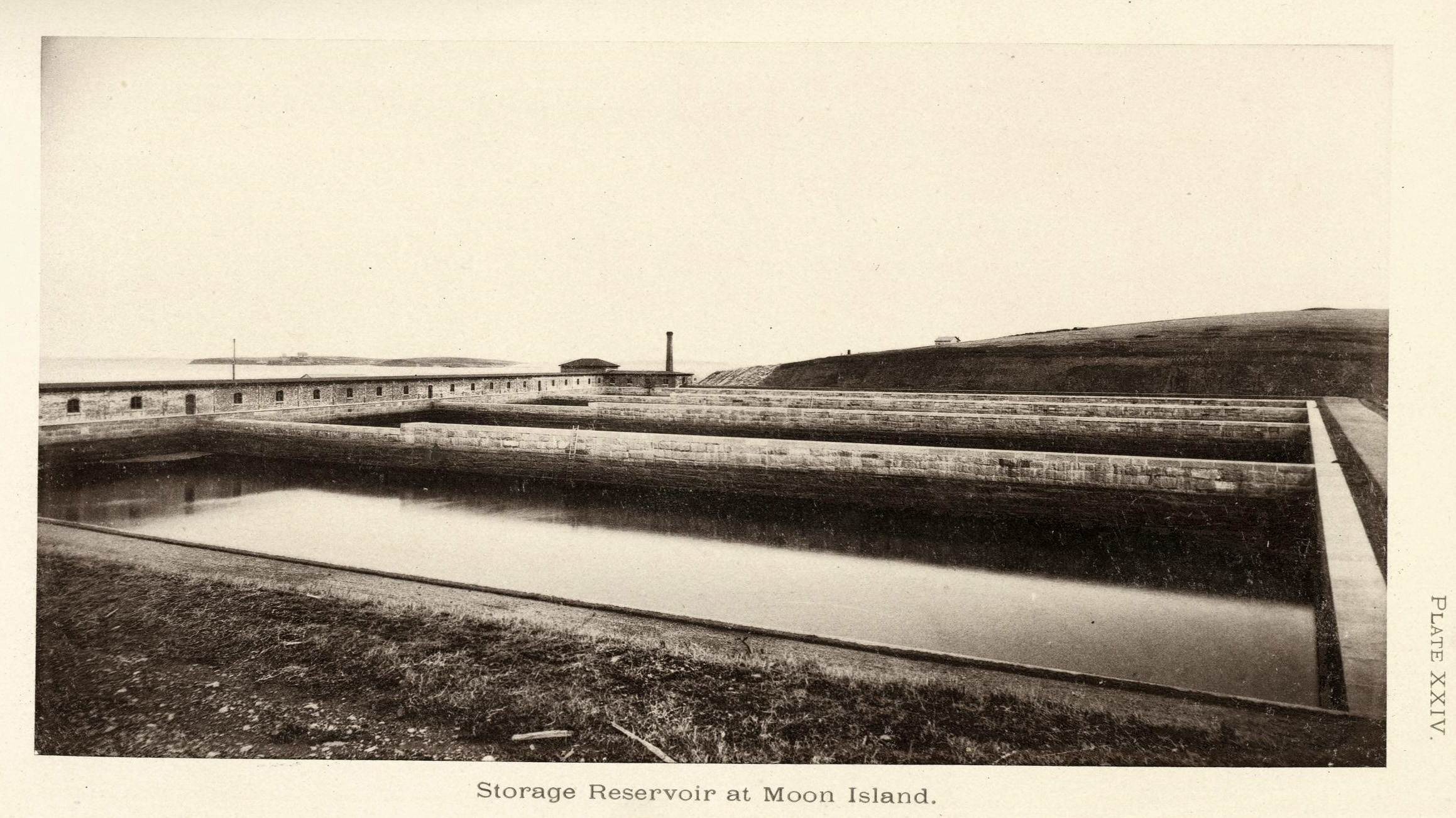

The City of Quincy housed the Moon Island sewerage facility. Moon Island served as the final destination for Boston’s sewage until 1968 when the city updated the Deer Island facility to handle the main drainage sewage. Reservoirs on Moon Island collected the raw sewage transported from the Calf Pasture Pumping Station. Here, reservoirs held sewage until releasing it into Boston Harbor with the outgoing tide.

Decades of dumping the city’s untreated sewage had negative impacts on Boston Harbor and local communities. Attempts to redress this pollution began In 1941, with the design of a waste treatment facility at Nut Island. Ernest efforts to clean the harbor began in the 1970s.

Nut Island

It took seven years to build the sewerage treatment plant at Nut Island, in the City of Quincy; construction began in 1945, and operations commenced in May 1952. Total construction costs were approximately $10 million.

Engineers designed the Nut Island sewerage facility to address environmental problems created by the release of untreated sewage into Boston Harbor. The Nut Island plant built in 1952 could not provide sufficient sewage treatment to protect the waters of Boston Harbor, however. Prompted by a lawsuit and investigation in 1982, the 1952 facility at Nut Island was demolished, and a new Nut Island Headworks facility opened in 1998. This newer facility can complete a secondary treatment of sewage, and thus remains in operation today. The Massachusetts Water Resource Authority maintains a public park on the island.

Deer Island

The facility on Deer Island in Boston Harbor is perhaps the most easily recognizable sewerage treatment plant in Boston. The distinctive large round tanks are readily spotted from airplanes, boats, and land across the harbor. The first primary treatment plant at Deer Island was built in 1968. In 1982, the establishment of the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA) led to the rehabilitation of sewerage treatment facilities on both Nut Island and Deer Island to create plants that could sufficiently treat Boston’s sewage for safe release into the Harbor.

Sources Consulted:

Photo Credits:

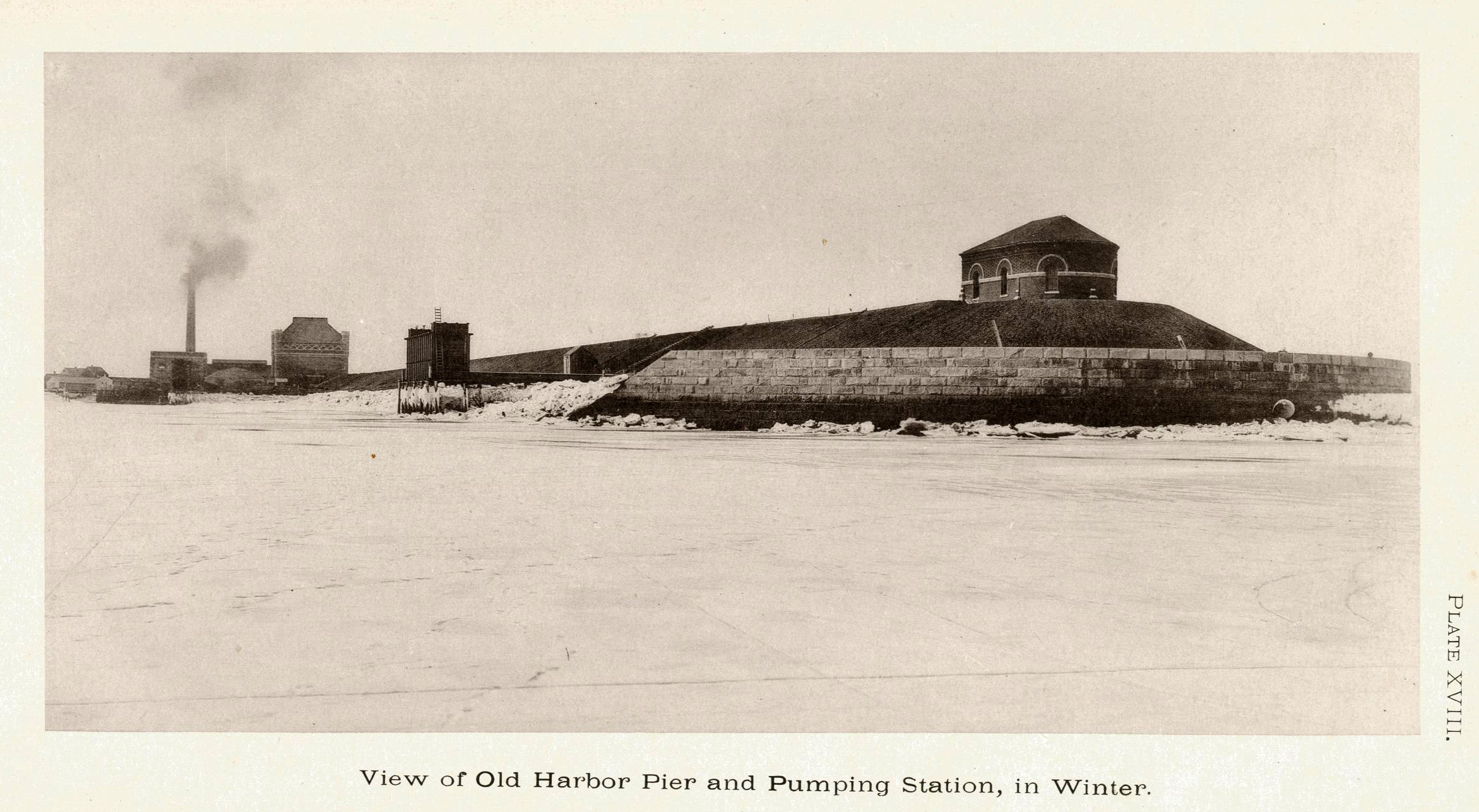

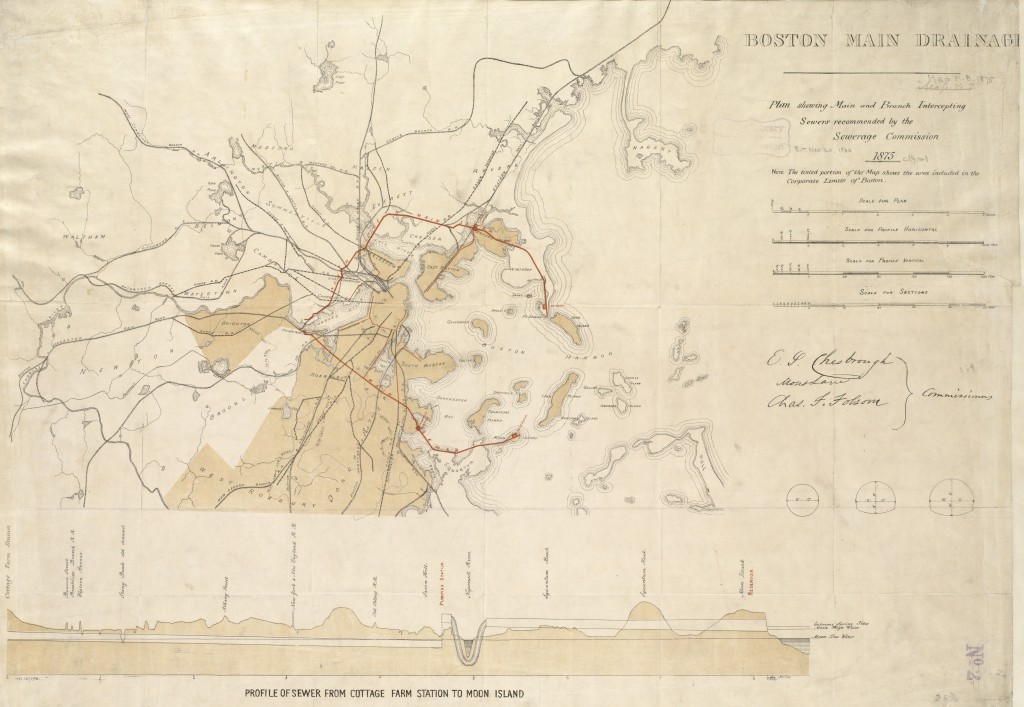

Boston’s new sewerage system, built in the 1870s and 1880s, was designed to take waste from the city and dispose of it miles away from the local population. The map below shows the newly constructed sewers that drained into the one sewer that led down to the Calf Pasture. Gravity allowed waste to travel from downtown Boston neighborhoods that sat on higher land, to Dorchester’s Calf Pasture on a lower elevation.

After the sewage reached the Calf Pasture Pumping Station, it still had a great distance to travel before reaching its final destination, Moon Island, west of the peninsula in Quincy Bay. To make the last leg of this journey, the station’s massive pumps lifted the sewage thirty-five feet to enable its journey away from the heavily populated city, past the oscillating tides, towards Moon Island.

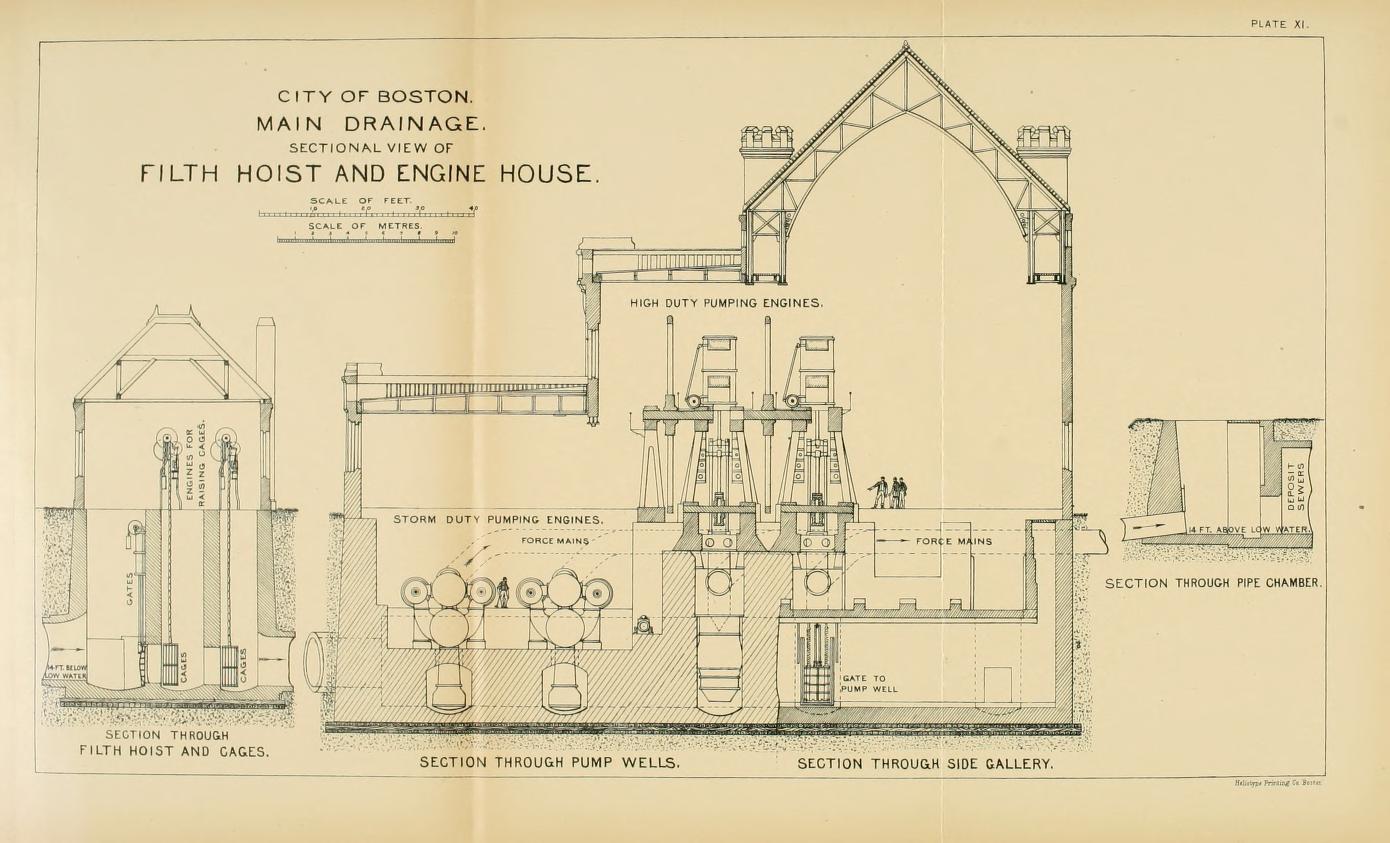

What’s in the pumping station? How does it work? An 1888 blueprint of the building illustrates the various functions of the large building.

The coal house held giant bins to store the coal that created steam power to run the boilers and power the integral pumps. The pumping station was large enough to store 2,500 tons of coal at once, since the pumping station burned over six tons of coal each day. Ships docked nearby on the peninsula to deliver new coal shipments to the pumping station’s elevated coal run.

This huge measure of coal fueled two major Leavitt pumps, which ran continuously throughout the day. Each engine could pump up to 25 million gallons of sewage per day. In the mid-1880s, the two engines pumped an average of just under 37 million gallons each day.

In some cases, excess storm water pushed the pumps to their limits. In preparation for this possibility, the engineers installed two additional emergency pumps. These two smaller storm duty pumping engines were used sparingly, because they were less fuel efficient than the major Leavitt engines. Still, they proved crucial when unexpected amounts of water came through the station.

Sources Consulted:

Photo Credits:

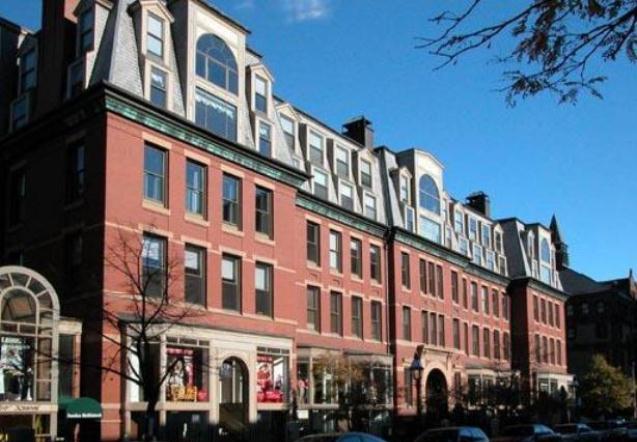

Architect George Albert Clough designed the Calf Pasture Pumping Station. Appointed the first City Architect of Boston in 1874, Clough oversaw the design, construction, and renovation of a number of prominent public structures in Boston during his nine-year tenure. These included: Boston Latin School, Boston English School, Suffolk County Courthouse, Congress Street Fire Station, and the Prince School on Newbury Street. Clough also submitted the first plans to be accepted for the Boston Public Library in 1880, and oversaw the first restoration of the Massachusetts State House in 1881. He played a role in the design of the waterworks systems in Chestnut Hill and Framingham, which provided Boston with a much needed alternate water source.

Born on March 27, 1843 in Blue Hill, Maine, Clough began his career working as a draughtsman for his father, who was a shipbuilder. After his father’s death in 1863, Clough moved to Boston to formally study architecture. He was employed and trained at the firm of Snell and Gregerson, where he stayed until 1869, when Clough left to open his own architectural office. He held the office of City Architect from 1874 to 1883.

((

The Calf Pasture Pumping Station was George Clough’s final project as Boston’s City Architect, as its construction was awash with controversy. Clough and the Superintendent of Sewers, William H. Bateman, approved the plans for the Main Drainage Works System presented by Ellis S. Chesbrough and his commission in 1876, and construction began on the Calf Pasture in 1879.

The City Council expected the construction of the facility would be carried out by skilled craftsmen from Boston. But, Clough dismissed the primary laborers and replaced them with men of his choosing; this sparked controversy, as the members of Boston City Council believed Clough’s new men were poor craftsmen.

Earlier, in 1881, an alderman on the City Council had accused Clough of neglecting improvements in the ventilation of the Council Chambers of City Hall, and called for his replacement as City Architect. On April 9, 1833, Clough lost the council re-election as city architect; he was replaced by Charles J . Bateman (1851-1940) who oversaw the completion of the pumping station.

After his removal from the post of city architect, Clough returned to private practice. In 1905 he established the firm Clough and Wardner and went on to design some 84 public schools in Massachusetts, New York, Maine, and Pennsylvania. He died in Brookline, Massachusetts in January 1911. Fourteen buildings designed by Clough, including the Calf Pasture Pumping Station, are now on the National Register of Historic Places.

Sources Consulted:

Boston City Council. Reports for the Proceedings for Municipal Years 1876, 1883, 1885. Boston: Rockwell and Churchill.

Clark, Eliot C. Main Drainage Works of the City of Boston. Boston: Rockwell and Churchill, 1885.

Engineering News and American Contact Journal, February 17, 1883, pg 163.

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form for the Calf Pasture Pumping Station.

Obituary of George Clough, Ellsworth (Maine) American, January 11, 1911, p. 6.

Marwell, Stuart; Burke, Bryan; Hudak, Andrew, “Calf Pasture Pumping Station”, Boston Public Library, BRA (Boston Redevelopment Authority) collection

Photo Credits:

When Boston’s City Architect, George Albert Clough, set out to design the structure that would house the pumps that would power the Commission’s proposed Boston’s Main Drainage System, he choose the prominent Richardsonian Romanesque style. Named for the American architect who initiated the Romanesque revival in the United States–Henry Hobson Richardson– who designed some of Boston’s most significant structures such as Trinity Church. Regal and proud, the Romanesque style reflected the proud accomplishment of creating a brand-new modernized sewerage system. Unlike today, when municipal buildings are often created to blend in with their surroundings, the Calf Pasture Pumping Station was designed as a visual landmark, a testament to the city’s advances in technology and sanitation. Although it wasn’t accessible to everyone, it was a public building and could demonstrate that Boston’s huge sewerage treatment project had been successful.

Richardsonian Romanesque is a medieval and fortress-like design characterized by the use of rustic brick and granite in contrasting colors, heavy columns, and stone arches. Buildings designed by Richardson and in his style were constructed throughout the United States. Richardson designed Boston’s iconic Trinity Church, rebuilt in the city’s new Back Bay neighborhood in 1877 after the Great Boston Fire of 1872 destroyed its previous structure on Summer Street. Other local Richardson contributions include, what is today, the First Baptist Church (known in Boston as “Church of the Holy Bean Blowers” for the trumpeting angels on its bell tower), the Quincy Library, a suite of town buildings in the center of Easton, Massachusetts, as well as a number of train stations, commercial buildings, and private residences in Massachusetts.

Henry Hobson Richardson was born in Louisiana and raised in the South. He came to Boston in 1855 to attend Harvard University and later when on to continue his architectural studies at Tulane and the Ecole de Beaux Arts in Paris. Strongly influenced by the French Romanesque style (itself a hybrid of Gothic and Romanesque architecture), he blended that sensibility with an enthusiasm for Medieval architecture when he returned to the United States from France in 1865. The result was a unique architectural style incorporating rough-hewn granite, stone arches, the mixed use of brick and stone, and castle-like peaked roofs rising above wide columns. Richardson’s first major commission came in 1870, the Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane (today known as the Richardson Olmsted Complex) cemented him as a major American architect, and he steadily gained prominence, although it was discovered after his death that he had gravely mismanaged his finances and left his family in debt.

The elements of the Richardsonian Romanesque style are specifically incorporated and clearly noticeable in the Calf Pasture Pumping Station. Although the outside is mainly built of grey granite (the red brick window-infills are modern), there is extensive use of multicolored brick and stone to create designs and patterns inside. The squat, fortress-like structure is lined with square and arched windows and stone arches. Castle turrets adorn the corners on each level and an imposing peaked roof caps the entire structure.

Although small changes have been made to the property over the years, it retains its essential character as a Richardsonian Romanesque building. Restoring and repurposing the Calf Pasture Pumping Station would be a valuable way to preserve a piece of H.H. Richardson’s architectural legacy and New England’s history.

Sources Consulted:

Photo Credits:

Until the late 19th century there was little organized effort to promote public health in the United States. With the growth of America’s urban centers in the mid-late 1800s, however, increasing population density brought public health challenges. By the turn of the 20th century, the United States had become the third most populous nation in the Western world, after Russia and France. Over 2 million immigrants arrived between 1871 and 1880 alone. This rapid growth was centered in America’s urban centers such as New York, Chicago, and Boston. Such population growth meant increased levels of human and industrial waste that needed to be removed, and strained the minimal existing infrastructure.

In the 18th century, Bostonians did not address waste in any organized or systematic fashion. Household waste and storm water routinely flooded basements and houses. Sometimes, people built small drains to take away both household waste and storm water; sometimes groups of people built a drain together and charged newcomers an access fee. These drains were built underneath roads, and used gravity to discharge waste directly into the nearest shoreline . Such drainage projects were built haphazardly and often damaged the local infrastructure.

These early drainage systems were not built to handle human waste. While household waste and storm water were removed from the city via these street drains, before the consolidation of drainage in Boston, human waste was collected in privies or outhouses. These simple systems consisted of a hole in the ground, often lined with rocks or boards. Privies required frequent upkeep, and needed to be cleaned out when they became full. People of means could hire private companies to clean out the privies; often, people simply filled in the rest of the hole with dirt, and dug a new privy hole somewhere else on site.

In the 1830s, Boston storm drains were consolidated under city control but new drainage problems arose as the city undertook many large scale land making projects that more than doubled the size of the city over the next century. Filling in the marshy tidal flats surrounding Boston created new neighborhoods and expanded the city. Many of these new lands were either at or above the high tide level, so gravity could not take care of waste drainage. In 1833, the city permitted the release of sanitary waste into household drains which led to a much larger problem. The city’s old drainage systems depended on the tides to pull the waste away from the city and out to open ocean; more frequently, the waste, both household and sanitary, remained when the harbor tides pulled out, leaving them to fester on the flats surrounding the city.

The introduction of the water closet and indoor plumbing in the second half of the 19th century exacerbated this waste problem. Similar to our modern flush toilets, a water closet uses water to quickly sweep away human waste. Early water closets emptied into privy vaults, but the added water filled these privies faster and often led to overflowing. City planners hastily devised a quicker way to get this dirty water away from the city and into the harbor. When water closets were attached to the already ineffective storm sewers, the harbor and tidal flats that surrounded the city became even more polluted as tides failed to pull away the waste.

The entire city faced this problem, declared the City Board of Health — “large territories” that “have been at once, and frequently, enveloped in an atmosphere of stench so strong as to arouse the sleeping, terrify the weak, and nauseate and exasperate everybody.” (Main Drainage Works of the City of Boston, Pg. 20) Officials believed that the stench and inadequate waste disposal were responsible for Boston’s high death rates . Outbreaks of diseases such as cholera, which is contracted through contaminated drinking water, added to the demand for a cleaner city. In 1875, the City created a commission of civil engineers to report on the state of sewerage in the city. The Commission’s report revealed the dire need for a new sewerage system, and proposed a plan for the construction of the Main Drainage System, with consolidated drains leading south of the city to the Calf Pasture at Dorchester.

Sources Consulted:

Photo Credits: