Since its closure as an active pumping station in the late 1960s, the Calf Pasture Pumping Station has been neglected. Currently, most windows are boarded up and a high fence surrounds the property as the various institutions on Columbia Point build and expand. The beauty of the building and the mystery of the inaccessible have led many people to wonder what the interior looks like.

UMass Boston’s Associate Provost Peter Langer toured the inside of the building in 2011, and took these photographs.

Several others have had access to the building, and recorded the building’s interior. Late in 2008, an artist entered the building, and documented their visit on the website Desolate Metropolis.

Have you been inside the Calf Pasture Pumping Station? Do you have observations or pictures? Please share these with us in the comments section below. in the comments below?

As Boston grew and its residents learned the dangers of pollution, they understood the problems resulting from the release of sewage into the harbor at Moon Island. Bostonians called for a cleaner harbor, and by the 1960s and 1970s treatment of sewage was rerouted to Deer Island.

But the Boston Water and Sewer Commission still used the Calf Pasture Pumping Station on occasion. In the 1970s, during heavy rains, excess street water was channeled to the pumping station, where it was treated behind the station, on the side of the building that faces the UMass Boston campus. Eager to end such use on their campus, in 1999, university administration began negotiations to purchase the property.

The Boston Water and Sewer Commission was reluctant to give up the Calf Pasture Pumping Station, because they would have to build a new facility somewhere else in the Boston area. Local politicians took up the debate. After a dozen years, in 2012 the university finally reached an agreement with the city and the Boston Water and Sewer Commission, and purchased the pumping station.

What is the future of the Calf Pasture Pumping Station at the University of Massachusetts Boston? How can it be used? Many faculty members and administrators have made suggestions for possible re-use of the building. There are many challenges to conquer before renovation can occur. These include environmental remediation at the site, and completing a structural report to assess the work needed to reuse the space.

Recently the University released a large twenty-five-year plan for renovations to the UMass Boston campus, but the pumping station is not included in this plan. The university did not yet own either the Calf Pasture Pumping Station or the Bayside Expo Center in 2007, when the 25 Year Master Plan was unveiled

Today, major redesign of the UMass Boston campus and the construction of new buildings and roadways are underway. In the new design, a new street will bring visitors in front of the majestic Calf Pasture Pumping Station, though its future use remains uncertain.

At present, boarded up windows and fencing secure the pumping station against general access. At the front of the building, construction of a new roadway has commenced, and the university prepares to build its first residential complex near the site.

Rehabilitation, preservation and reuse of the Calf Pasture Pumping Station will require great financial resources as well as vision. This historic structure, its historical and architectural significance documented by a National Historic Register nomination, remains at risk. The physical condition of the building continues to deteriorate, as local development and the need for space put additional pressure on this historic site.

The Calf Pasture Pumping Station provides us with access to multiple stories of the past that have relevance to the present. It engages histories of technology, architecture, public works, public health, labor, environment, neighborhood, housing, and politics.

What ideas do you have for bringing these histories into the present, for the benefit of Boston’s citizens? What histories matter to you?

The Calf Pasture Pumping Station is a prime example of industrial innovation and engineering and stands today as an architectural and historical landmark on Columbia Point. Unused for over forty years, the empty but impressive structure begs the question, what comes next?

Restoring and reusing such a pumping station is a daunting task, but there are successful models undertaken at similar structures elsewhere in the United States, with a variety of interesting results. How have other communities restored, preserved, and reused such impressive reminders of the history of public health and technological innovation? What can these models teach us about the possibilities for the future of the Calf Pasture Pumping Station, and the challenges we might encounter with their preservation?

Pumping Station No. 1

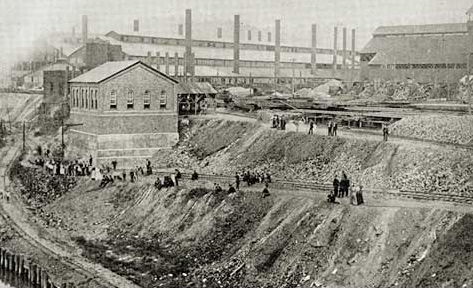

Homestead, Pennsylvania

Some pumping stations have a surprising history. In Homestead Pennsylvania, “Pumping Station No. 1” is the last remaining structure of Homestead Steel Works. Purchased by Andrew Carnegie and incorporated into Carnegie Steel Company in 1883, Homestead Steel Works was one of Carnegie’s largest producers of steel. In 1892, Homestead’s Pumping Station No. 1 was the site of a violent clash between workers striking for better pay and working conditions, and Pinkerton agents hired by Carnegie Steel to break the strike. One of the strikers was killed inside the pumping station by a Pinkerton bullet.

Homestead Steel Works closed in 1986, and within the next few years, most of the structures on the site were dismantled. In 1988, the site was sold to the Park Corporation which began to clean and prepare the building for restoration and new construction. There were several environmental issues to overcome, especially soil contamination from lubricants and asbestos. Structurally, the pumping station on the Homestead grounds was sound the land and building were filled with slag, a byproduct of manufacturing steel. The original ground floor of the pumping station, as well as the river landing that the workers and Pinkertons disembarked from during the 1892 conflict, both remained beneath the infill.

Ultimately, the preservation of Pumping Station No. 1 resulted from the actions of two groups with interests in preserving the site–Continental Real Estate, and the Battle of Homestead Foundation (BHF), a group of local citizens, historians and educators. In the 1990s, Continental Real Estate purchased the building, and BHF implemented interpretive and educational programming at the site.

Today Pumping Station No. 1 is owned by the Steel Industry Heritage Corporation, which is dedicated to preserving the memory of the pivotal Homestead Strike through educational programming. Part of the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area, the Homestead pump house provides space to support community events dedicated to education and the arts. These include a “Heritage Market” and a “Bike Friendly Eco-Center,” with specially designed amenities for cyclists traveling the bike paths that run along the edge of the river, encouraging them to take a rest and explore its valuable history.

Eden Park Pump House

Cincinnati, Ohio

The Eden Park Pump House in Cincinnati, Ohio, was designed by well-known architect Samuel Hannaford in 1889; it sits in the historic Eden Park, originally on the banks of a large man-made reservoir. The pumping station ceased pumping operations in 1908; in 1939 it was repurposed as a central radio communications center for the city’s fire and police departments. It remained in use as a communication center until the mid-1980s when it was then used for storage and eventually fell into disrepair. In 2012 a former city employee, Jack Martin, leased the property from the city with the proposed plan to restore it and give it new life as a microbrewery.

The “Brewery X” project showcases the struggles in renovating a 19th century pumping station and working with the local community to establish a new, business use for the property. Jack Martin, a retired architect was attracted to the Eden Park Pump House for the site of his brewery partly because of Cincinnati’s history and legacy of beer making. The city approved Martin’s initial plans for interior and exterior restoration and reconstruction , but the project has been delayed by the multiple and varied challenges posed by investors, community, zoning and architectural boards, and the Cincinnati City Council. As of April 2015, priced at an estimated $3.5 million, had yet to be completed.

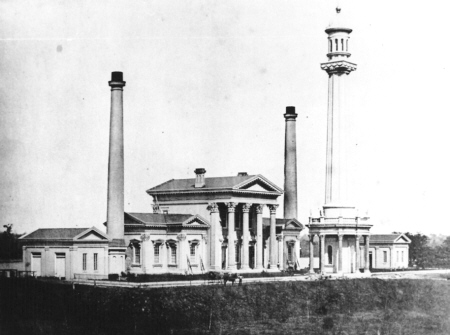

Louisville Water Company Pumping Station No. 1

Louisville, Kentucky

The successful renovation of the Louisville Water Company’s Pumping Station No. 1 preserves a significant architectural landmark and Louisville historical resource. Architects Theodore Scowden and Charles Hermany designed this water pumping station, which operated from 1860-1912. This Classical Revival structure resembles a two-story temple, with wings on both sides. The pumping station was nominated to the National Historic Register in 1971. Renovations began that same year, and continued until 2013. Finally restored to its original condition, exterior and interior renovations have cost around $2.3 million.

The Louisville Water Company’s Pumping Station No. 1 now houses a WaterWorks Museum of science and history; exhibits and programming explore the scientific and engineering innovations of the pumping industry in Louisville, public health, and the architectural and historical significance of the building.

The city of Louisville has been very supportive of the Water Works Museum project, which has been conceived and funded by the Louisville Water Company, the owners of the site. “Louisville Water’s history is Louisville’s history and it is rich with scientific and engineering innovation and architectural achievement,” said Louisville Water President & CEO Greg Heitzman in 2012, “This project is part of our longstanding commitment to preserve the infrastructure and stories about the people who have guided us to where we are today.”

Are there examples of successful restoration, rehabilitation and reuse of such industrial structures in your community? What has worked? What are the challenges?

Sources Consulted:

Photo Credits: