Until the late 19th century there was little organized effort to promote public health in the United States. With the growth of America’s urban centers in the mid-late 1800s, however, increasing population density brought public health challenges. By the turn of the 20th century, the United States had become the third most populous nation in the Western world, after Russia and France. Over 2 million immigrants arrived between 1871 and 1880 alone. This rapid growth was centered in America’s urban centers such as New York, Chicago, and Boston. Such population growth meant increased levels of human and industrial waste that needed to be removed, and strained the minimal existing infrastructure.

(Source: “Boston, as the Eagle and the Wild Goose See It”, 1860, Boston Public Library, Print Department, https://www.digitalcommonwealth.org/search/commonwealth:cf95jj42g) (Click to enlarge image)

In the 18th century, Bostonians did not address waste in any organized or systematic fashion. Household waste and storm water routinely flooded basements and houses. Sometimes, people built small drains to take away both household waste and storm water; sometimes groups of people built a drain together and charged newcomers an access fee. These drains were built underneath roads, and used gravity to discharge waste directly into the nearest shoreline . Such drainage projects were built haphazardly and often damaged the local infrastructure.

These early drainage systems were not built to handle human waste. While household waste and storm water were removed from the city via these street drains, before the consolidation of drainage in Boston, human waste was collected in privies or outhouses. These simple systems consisted of a hole in the ground, often lined with rocks or boards. Privies required frequent upkeep, and needed to be cleaned out when they became full. People of means could hire private companies to clean out the privies; often, people simply filled in the rest of the hole with dirt, and dug a new privy hole somewhere else on site.

In the 1830s, Boston storm drains were consolidated under city control but new drainage problems arose as the city undertook many large scale land making projects that more than doubled the size of the city over the next century. Filling in the marshy tidal flats surrounding Boston created new neighborhoods and expanded the city. Many of these new lands were either at or above the high tide level, so gravity could not take care of waste drainage. In 1833, the city permitted the release of sanitary waste into household drains which led to a much larger problem. The city’s old drainage systems depended on the tides to pull the waste away from the city and out to open ocean; more frequently, the waste, both household and sanitary, remained when the harbor tides pulled out, leaving them to fester on the flats surrounding the city.

Head of the commission assembled to investigate the state of sewerage in Boston in 1875. He was previously head engineer for the design and construction of America’s first comprehensive sewerage system in Chicago.

Source: The Chicago Historical Society. (Click to enlarge image)

The introduction of the water closet and indoor plumbing in the second half of the 19th century exacerbated this waste problem. Similar to our modern flush toilets, a water closet uses water to quickly sweep away human waste. Early water closets emptied into privy vaults, but the added water filled these privies faster and often led to overflowing. City planners hastily devised a quicker way to get this dirty water away from the city and into the harbor. When water closets were attached to the already ineffective storm sewers, the harbor and tidal flats that surrounded the city became even more polluted as tides failed to pull away the waste.

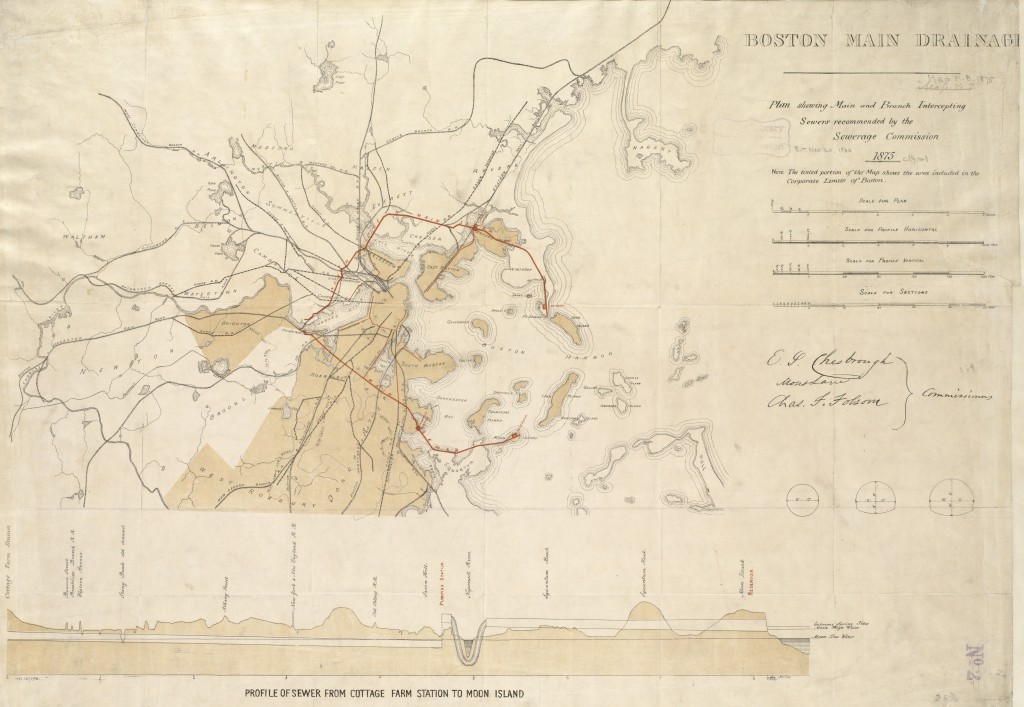

The entire city faced this problem, declared the City Board of Health — “large territories” that “have been at once, and frequently, enveloped in an atmosphere of stench so strong as to arouse the sleeping, terrify the weak, and nauseate and exasperate everybody.” (Main Drainage Works of the City of Boston, Pg. 20) Officials believed that the stench and inadequate waste disposal were responsible for Boston’s high death rates . Outbreaks of diseases such as cholera, which is contracted through contaminated drinking water, added to the demand for a cleaner city. In 1875, the City created a commission of civil engineers to report on the state of sewerage in the city. The Commission’s report revealed the dire need for a new sewerage system, and proposed a plan for the construction of the Main Drainage System, with consolidated drains leading south of the city to the Calf Pasture at Dorchester.

(Source: Boston City Document No. 3 1876) (Click to enlarge image)

Sources Consulted:

- Clarke, Eliot C. Main Drainage Works of the City of Boston. Boston: Rockwell & Churchill, 1888.

- Melosi, Martin. The Sanitary City: Environmental Services in Urban America From Colonial Times to the Present. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2008.

- Tarr, Joel. The Search for the Ultimate Sink: Urban Pollution in Historical Perspective. Akron: University of Akron Press, 1996.

Photo Credits:

- “Boston, as the Eagle and the Wild Goose See It”, 1860, Boston Public Library, Print Department

- Clarke, Eliot C. Main Drainage Works of the City of Boston. Boston: Rockwell & Churchill, 1888.