For many students, getting an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) is the first step to changing their learning experience. The process begins when a teacher or family member refers the student to be evaluated for special education services. From there, the state is responsible for evaluating the student’s academic performance and social behavior. A district representative will observe the student and conduct an evaluation.

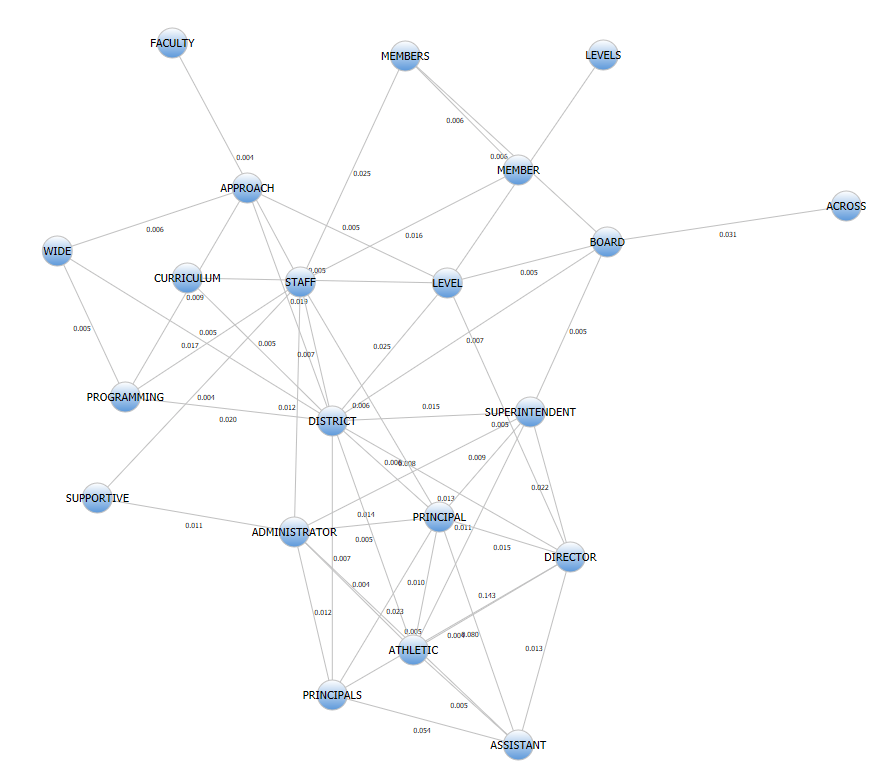

This report is brought to a meeting, where the IEP team, made up of the district representative, special education director, teachers, family members, and the student themselves if they are older than 14, discusses academic goals and needs. The IEP meeting is how the team determines if and what special education services are needed. Based on the outcomes of the discussion, an IEP is drafted and implemented.

This process can be intimidating and stressful for families and students, sometimes culminating in them contributing less to the IEP. Linguistic and cultural barriers and not having enough information can silence family members and students of color in these meetings (Wolfe and Durán 2013). Family members can request the presence of both a language interpreter and a certified IEP Parent Member, a fellow guardian of a student with a disability who ensures the family is heard during the process.

Families and students have deep insights into the student’s learning and what structure of support would work best. It is important that the special education director and teachers create space for families and students to share their perspectives and meaningfully contribute to the plan (Reiman et al. 2010). In a survey, family members reported good experiences of the process when teachers treated them as equal decision makers (Fish 2010). This could look like asking families to introduce the student to the rest of the IEP team or providing them a chance to add to each teacher’s report.

The best way for families to advocate for their students is to help the team get a clear picture of who the student is, how they learn best, and what types of supports would be most beneficial. Families should come prepared to discuss their students’ past academic performance, goals for the future, what has worked and not worked, interests and extracurriculars, and any strategies that work for the student at home. These insights have the potential to inform how teachers imagine supporting students in the classroom. For instance, knowing that when a student does homework they typically take quick move breaks that help them stay focused may encourage the team to put similar accommodations in place for when the student takes exams.

Though the IEP process is daunting, ideally a team will emerge from the meeting with a plan that meets the students’ needs and provides scaffolded supports towards achieving clear goals. Families play an important role in the process, and it is incumbent upon the other members of the IEP team to keep the family informed, answer their questions, and solicit their opinions.

By Anika Lanser, Research Assistant at the Center for Social Development and Education