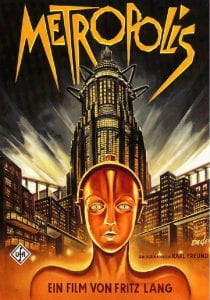

Metropolis (1927)

Metropolis (1927), a movie by Fritz Lang with a script written by his wife, Thea von Harbou, is considered to be an enduring classic film, an epic and beautiful cinematic masterpiece. There exists so much discussion about the aesthetic of this visually stunning film, an example of German Expressionism at it’s finest. Yet at the core is a deep look into Capitalism, through a narrative that veers from desperation into a fairy tale with an unrealistic, yet positive, end to class conflict. Set in the year of 2026, there is an unnerving sense of familiarity as the story unfolds, and to lies that we are still being told by those who own the Capital upon which our economy depends. Was Lang’s vision accurate?

Following the First World War, Germany was brought under tight control globally through treaties, and world powers which imposed reparations upon them. The Weimar Republic was still quite authoritarian, with economic challenges that were exacerbated by the hyperinflation of the early 1920s, a heavy weight in the struggling average citizen, who had already been through quite a tumultuous time during the war, under the Nazi regime. In contrast, the US continued to rise in power and influence over the world, bringing with it dreams of the successes of the Captains of Industry in their imagined beneficence. Fritz Lang’s masterpiece was a statement on the morale of the worker during this time. Metropolis is a vast and prosperous futuristic city, where we are introduced to it’s elite and elegant upper classes as they enjoy life of leisure, education and competition, even as the downtrodden, exhausted and despairing workers toil unseen “below”, in the underground Worker City. The film was released in 1927 and has long been considered to be a groundbreaking work of science fiction, with novel special effects, and a theme that became a well used trope in later sci-fi – that of the intelligent robot. The tale is carried on with undertones of religious faith, and political allegory.

The city of Metropolis resembles a futuristic city from the comic books of yore. Like the equally fictional Gotham, New York of the time seems to have been an influence over the chosen aesthetic of towering buildings with elegant and streamlined architecture, run through with efficient transport railways; flying cars or small planes traversing the intermingled overpasses full of commuters in their vehicles (a familiar sight to any city dweller, past of present, who needs to rely on cars). The hierarchy here is clear – there seems to be no middle class that we are made aware of, only “the haves, and the have-nots”. There is a ruling class shown as being citizens of the fine city, the upper class, gorged on their own privilege. This “Club of the Sons”, are representative of the elite populace, led by the city’s own “Master” – industrialist and Capitalist, Joh Fredersen (Alfred Abel). The “workers”…trapped in a dreary existence, exhausted and shopworn in their toils at dangerous and dirty hard labor… live in the underground “Worker’s City” (truly slums), and work there too, in labor intensive “factories”. These workers hit a note of empathy for anyone who has ever worked long hours, or have done back-breaking work. Robotic and dead eyed, clearly worked beyond reason, desperate and yet, strangely docile, these workers are seemingly forced to work to the breaking point to survive. They keep the machines going smoothly, enabling a life of leisure and, we imagine, Utopian existence to the privileged oppressors above. The upper echelon barely seems aware of their existence, and when they are spotted, are stared at as though some wild beast had escaped it’s zoo. They frolic in the Garden while they stand on the backs of the workers, and they are unconcerned. In an effective intro, we see the workers as they queue up to enter the factories, moving in rhythm, like cogs in a machine. They look down, bent forward with the weight of their toils and lot in life. Invisible by design, the workers carry on, day in and day out. Meanwhile, back at the Garden, Maria (Brigitte Helm), an angelic figure, guides a group of children to the very Garden of the elite, striking stars into Freder’s (Gustav Fröhlich) eyes. Freder, being the son of the Master of the City, Joh – is surprisingly innocent in his privilege, and he follows the throng once they are turned back by the servants in the Garden, clearing the elite from the unsightly experience of viewing the working poor. Freder manages to reach the lower levels of Metropolis in his pursuit of Maria, only to discover the horrors of the realm, witnessing firsthand the enslaved, and being stirred to confusion and a need to help them in their plight. While there, workers keep up a frantic pace and yet, the machines start to run amok, uncontrolled (a fine example of “lean management” at its worst, I’d argue). The scene culminates in an explosion that causes numerous deaths and injuries, and a “vision” in which Freder witnesses the top of the factory platform to become a big, open, demonic mouth, there to be fed the workers in sacrifice to production, the great god Moloch. Running back to his father, he implores that the plight of the workers below be alleviated, only to be met with utter indifference, and the attitude that dismisses any human empathy shown by Freder.

Freder finds Maria preaching to the poor working classes, a prophecy. There will be a “Mediator” known as the “Heart”, who would stand in between the “Head” (Upper classes) and the “Hands” (workers), bringing good for all. He becomes inspired (and more than a little dazzled by Maria), deciding that her message is true and that he would do this to impress his love for her upon her. But his attempts are met with scorn and he is dismissed, now looked upon with suspicion by his father…who, it turns out, also knows a good opportunity to exploit others when he sees one. Joh seeks out an old “frenemy”, the wild haired mad scientist Rotwang, a former suiter of his dead wife, who still carries q torch. He asks Rotwang to build a robot to use to manipulate the workers, asking that it be clothed in Maria’s likeness to disrupt rebellious efforts. Rotwand, it turns out, has other ideas…after all, the love of his life left him heartbroken, choosing Joh, before she died giving birth to Freder. Rotwang instead plots to employ the robot to foment chaos and destruction of the workers and the worker city, which would cripple and possibly destroy the life of the elites above, ruining Joh in the process. The movie then brings us down the path of ruin, with Robot-Maria sowing discord and mindless uprising with deceptive guidance in which they destroy their own homes and nearly kill their own children. I find myself in wonder at the depiction of self-harming direct action without thought, itself implying perhaps that workers aren’t smart enough to be trusted without a “helping hand” from above.

Workers of Metropolis at shift change

The first of the narratives we see presented in Metropolis is set up to show us the effects of unrestrained capitalism. There is a great divide…a CHASM… between social classes. Lang brings us to a society in which unparalleled economic inequality has necessitated the existence of a worker class that can only be compared to slavery, with no middle class nor “upward mobility” in sight, no way to better such a dreary existence. We see the rampant dehumanisation of workers and disregard for their well being. They look defeated and act like robots in their action, repeating and lifeless, with no purpose but to be a disposable part. Class war is bubbling up, readying to set the stage for rebellion. The narrative continues along to describe to us how the ruling class uses their power to control the workers and keep them docile, unequipped for any uprising in their depressive and depleted state. There is still an undertone of anger, of suffering to the brink of having nothing to hope for, but also a point at which there is nothing left to lose. It shows us the machination of the rulers above, manipulating and deceiving the workers, employing a surveillance state out to control any thought that they may step outside of their decided roles. With the addition of religious metaphors (always a popular escape from suffering of the masses), we see a theme of salvation begin to be woven in, but…to what end? It weaves a tale that a savior can be found only from Above, as it were, which in itself upholds the ideals of hierarchical social class. There is the Head, Heart and Hands in their mythology, as they wait for the Heart to arrive in their midst. Freder is that Heart of course, fulfilling a role as the mediator between the Hands (working class) and the Head (ruling class). The end is hopeful and dreamy; the worker foreman is met by the hands of Joh, compelled by his son Freder. The ending leaves me with questions, unanswered. The truce we witness leaves us no details, no knowledge about how this would play out – the workers are now homeless, their jobs, still unsafe; the rich still live carefree and it can be imagined they may not be so compliant at sharing that wealth and privilege. The film doesn’t provide us with any answers to these questions. Instead, it gives us a fairy tale ending that leaves the message of the main body of the movie lost in the aether, run over by the Deus ex Machina. Freder, a dreamer who is surprisingly pure and innocent considering his father’s cut-throat practices, has somehow bumbled his way to the role of a political/economic mediator, seeking to bring peace between the social classes in order to win over his love. We are expected, somehow, to accept this ending with gratitude and hope, despite having witnessed the callous elites and the desperate and unfortunate workers.

This movie will always be a gorgeous piece of Expressionist joy, visually, executed artfully in all aesthetic points. There is much admiration to be had in the beauty presented for the eyes – the city scapes, the novel special effects, the amazing sets and the costumes (most especially that of the Robot herself). The message was meant to give uplifting hope to a tumultuous world in post war Germany, to a rather disheartened populace. Capitalism wasn’t so critiqued then as it is now, as captains of industry were seen as heroes and innovators, leaders of our future, much as they present themselves today. We can compare much of the story to narratives we see now, the stark contrasts of the Rich and the working Poor – knowing well that the suggested magic of Love Saves All presented to us by Lang isn’t a shiny bright promise of a golden future, but a continuation of opportunity to be manipulated by the ruling class.