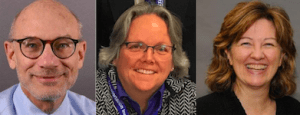

Left to right, Gerontology Institute Director Len Fishman, associate professor Elizabeth Dugan and professor Jan Mutchler. Fishman, Dugan and Mutchler appear in photos below.

UMass Boston gerontologists offered legislators two suggestions for state government in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic: Help researchers better understand what has happened to older adults and get elder Massachusetts residents prepared for a more challenging future.

Gerontology Institute Director Len Fishman, associate professor Elizabeth Dugan and professor Jan Mutchler all appeared individually at a May 15 virtual listening session hosted by the legislature’s Joint Committee on Elder Affairs. They joined a wide range of advocates, policymakers and other members of the public to describe the impact the pandemic has had on older adults and what state government should do to help.

Fishman pointed out that nursing homes already collect large amounts of health information about residents for the federally mandated Minimum Data Set, a standardized assessment document, that could be used in evaluating facility performance. However, he told legislators that more detailed data was needed from nursing homes, where about 60 percent of Massachusetts residents who died from the virus had resided.

He said nursing homes should be required to collect and report a limited amount of additional individual-level information “that would transform our ability to manage the pandemic in nursing homes, starting with basic epidemiology, the prevalence of COVID and the incidence of new cases.” He said other reporting items might include medications given to treat the virus in nursing homes, hospital and emergency department visits, as well as deaths from COVID-19.

He said nursing homes should be required to collect and report a limited amount of additional individual-level information “that would transform our ability to manage the pandemic in nursing homes, starting with basic epidemiology, the prevalence of COVID and the incidence of new cases.” He said other reporting items might include medications given to treat the virus in nursing homes, hospital and emergency department visits, as well as deaths from COVID-19.

Fishman said that information would allow analysts and researchers to answer critical questions, such as which nursing home staffing patterns and care processes are associated with low incidence of COVID-19, how the effects of virus treatments differed between nursing home residents and other populations and which respiratory therapies are most helpful in preventing hospitalization or death.

He said the information could “save hundreds, if not thousands, of lives and avoid untold suffering. But it would require our state government to act in a new and bold way by adopting 21st century data analytics that are the bread and butter of researchers and other analysts in the public and private sectors.”

Dugan described work she and her UMass Boston research team has done recently to apply their Massachusetts Healthy Aging Data Report to incidence of COVID-19 in the state.

The report is a comprehensive look at 179 health indicators for older Massachusetts residents, producing detailed town-level information about local elders. Dugan and her team have isolated information about conditions that apply commonly to COVID-19 patients — such as lung issues, hypertension and diabetes – in an attempt to identify areas of the state where older residents may remain more vulnerable to the virus.

But Dugan also stressed the need for access to information, particularly detailed data on fatalities, for researchers to be able to provide their best recommendations and guidance to legislators and other policymakers.

But Dugan also stressed the need for access to information, particularly detailed data on fatalities, for researchers to be able to provide their best recommendations and guidance to legislators and other policymakers.

“It looks like we’ll be living with the virus for some time and data access can help us adapt to this new reality, and inform smart policy and programs going forward,” said Dugan.

Mutchler noted that older Massachusetts residents were already struggling financially before the outbreak of COVID-19. Almost certainly, their circumstances will become more difficult in the immediate future.

The Elder Index, an online resource tracking the realistic living expenses of older adults in every U.S. county, identifies relatively high costs for elders in Massachusetts. The index, developed by Mutchler’s Center for Social and Demographic Research on Aging, and state income data shows older adults living independently in Massachusetts already faced one of the nation’s highest rates of elder economic insecurity.

Mutchler noted that many elders continued to work in order to make ends meet. About one in every four Massachusetts residents age 65 or older worked last year. Very high unemployment rates, which are already the case, pose particular problems for older adults.

“For them, employment disruption often ends up having permanent consequences,” she said. “In this downturn, with so many people competing for jobs, older workers may have an especially hard time. Additional job loss may occur because of health vulnerability.”

“For them, employment disruption often ends up having permanent consequences,” she said. “In this downturn, with so many people competing for jobs, older workers may have an especially hard time. Additional job loss may occur because of health vulnerability.”

Mutchler recommended state officials take a series of steps to support older residents who may face greater economic insecurity, including:

- making sure people know about existing assistance programs for fuel, food and other necessities.

- taking older people into account in strategies to reopen the economy.

- making sure older people understand long-term implications they face drawing down retirement resources and taking early Social Security benefits.

- strengthening the capacity of local councils on aging and other organizations providing information to residents seeking to bridge the gap between income and living expenses.

Leave a Reply