Researchers Marc Cohen and Jane Tavares know how crucial federal programs such as Medicaid health insurance and SNAP food assistance are for the most vulnerable older adults. “Our social safety nets are keeping so many people afloat,” says Tavares, a research fellow with the LeadingAge LTSS Center @UMass Boston. “Coming off a pandemic, with inflation rising, it’s especially critical now to serve such a vulnerable population,” agrees Cohen, co-director of the LTSS Center and research director of Community Catalyst’s Center for Community Engagement in Health Innovation.

Medicaid’s current eligibility rules—which rely on income standards based on the Federal Poverty Level and stringent limits on financial assets—exclude many older adults whose health and financial security are vulnerable. The researchers set out to quantify how many more people could be helped with varying eligibility standards. They published their study, “How Medicaid Financial Eligibility Rules Exclude Financially and Medically Vulnerable Older Adults,” in the most recent issue of The Journal of Aging & Social Policy.

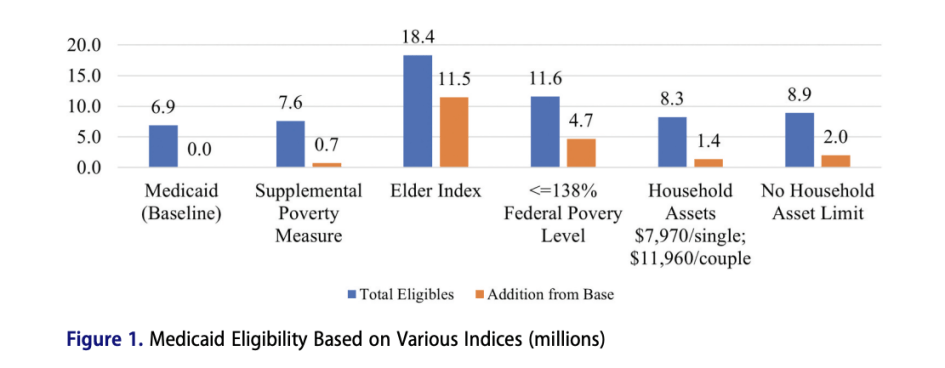

To determine who might benefit from loosening Medicaid’s eligibility rules, Cohen and Tavares used data from the nationally representative Health and Retirement Study and applied five alternative criteria for eligibility:

- the Supplemental Poverty Measure, which factors in some expenses such as taxes and healthcare costs but also counts some noncash benefits as income;

- the Elder Index, developed at UMass Boston, which determines the basic cost of living (including housing, healthcare, food and more) for older adults in each county of the U.S., offering more accurate accounting;

- 138 percent of the Federal Poverty Level, which is in line with the threshold for non-elderly and non-disabled adults;

- allowing for household assets of $7,970 for single adults and $11,960 for couples;

- no limits on household assets.

From a baseline of 6.9 million people who qualify for Medicaid based on current eligibility standards, the researchers saw the number of additional qualified participants range from 700,000, using the Supplemental Poverty Measure, to 11.5 million using the Elder Index. Raising the asset limit or not limiting assets at all adds 1.4 million and 2 million more, respectively, and using 138 percent of the Federal Poverty Level would qualify 4.7 million more older adults.

The researchers were surprised by how much the profiles of the additional eligible people look like those who already qualify for Medicaid. Using the Supplemental Poverty Measure, for example, the 700,000 additional people “have nearly identical health profiles,” Tavares says. “And their assets are very low. These are people who probably should be on Medicaid.”

Using the Elder Index, which adjusts for regional cost-of-living differences, “you see people who are a little healthier and a little less diverse racially and ethnically,” Tavares says. “So we’re adding more of the lower middle class white population. It’s an interesting balance, because people who currently qualify for Medicaid are typically already in dire straits financially and in terms of their health.” Better health insurance typically means more preventive care, meaning potential healthcare savings down the road.

“These are the trade-offs,” Tavares says. “Pulling different levers really changes the profile of who qualifies. We have a huge wealth gap in the U.S. for racial and ethnic minorities. If you raise the income limit, you bring in more people of color who don’t tend to have saved assets. If you raise the limit on household assets, you bring in a lot more white people.”

Making changes to Medicaid eligibility will always be a political battle, Tavares notes, with some policymakers afraid of offering benefits to so many people that the government can’t pay for the program. The bottom line of their study, she says, is that “we’re not talking about a massive number of additional people. And they look like people who could benefit tremendously from the coverage.”

3 Pingbacks