By Kati Albert

Early in the morning during the last week of the Plymouth Field School, a general question went out to the students: “Does anyone know how to use a video camera?” Tentatively, I raised my hand. I didn’t tell anyone I had only edited films before, was a self-taught home-movie maker, and only had experience taking still shots. Still, I volunteered myself, because in my mind there was a first time for everything, including shooting footage with a video camera I had never worked with before. Ten minutes later, I had a new video camera in my hands and the mission to begin filming the excavations in progress.

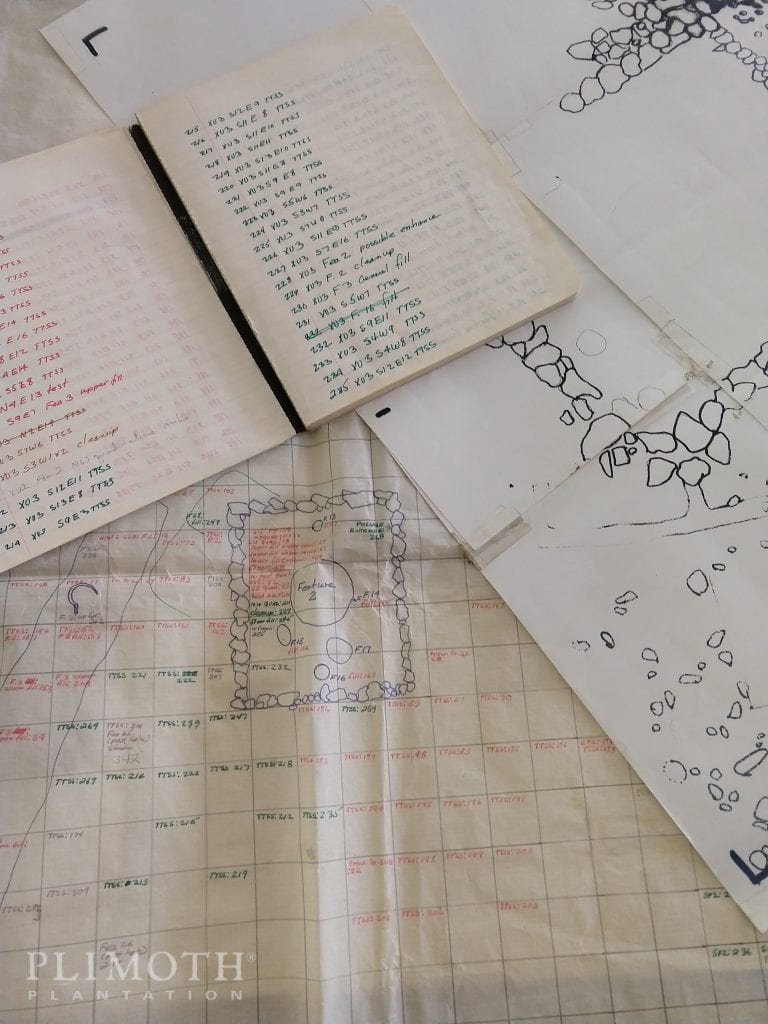

There was a reason for the video equipment on the site. As part of the exhibit for the Plimoth Plantation Museum, the Fiske Center for Archaeological Research wanted to create a short film to complement the artifacts and text on display in a new exhibit that in the works. The film would also explain why we are studying Burial Hill, what we are looking for, and what some of the finds were from the 2019 field season. My vision for the film was to be a showcase for the students’ work as they excavated, screened, drew illustrations of the stratigraphy, and found artifacts in the field.

I felt honored to be given the task of documenting the excavations “on film”. It was a phenomenal opportunity to be creative and to hone my skills as a filmmaker. I was given free reign to wander the site, capturing both the exciting discoveries, and turning the mundane processes of archaeology into visually compelling art. Everyone was very supportive of my efforts, and willing to explain what they were doing, or give a short interview about their experiences at the field school.

Filming on an open excavation site was challenging to say the least, especially without any time to plan what I wanted to record. As such, I had little choice but to film “guerrilla style”, with the camera clutched in my hands and my ears and eyes constantly on alert for any interesting find or insightful conversation. I was poised at the ready for something worthy of being documented to happen anywhere on the site.

Of course, I was only a one-woman crew, and the field was not a soundstage, nor anything close to a controlled environment for filming, and this was reflected in the daily footage. For every great scene I shot were dozens of shots that were unusable because of too much background noise, too much shaking, or the action was caught just a split-second too late. I could not get as close to the some excavations as I wanted to which cost me informative visuals and precious explanatory dialog. I regretted letting those opportunities slip past my lens.

Nevertheless, I was proud of what I shot. In total, I had recorded about 35 gigs (several hours) of footage over the course of a day and a half. I caught so many interesting and beautiful moments that show the hard work of the excavators and the complex nature of Burial Hill. So much of the archaeology translated well to a visual medium, including screening, sampling, and stratigraphy profiling. Additionally, I was glad that footage captured the feeling of being in the field, as well as the efforts of the students as they dug. This was because I had been adamant that I did not want to recreate any scenes of discovery, but instead I wanted to create an atmosphere of authenticity. I would rush over and try to capture scenes and exchanges between the students as they were happening.

Now that I had finished shooting, the next step was editing—a process that still has not ended.

Much like the unofficial rule of thumb for archaeology, “for every day in the field you can expect 3 or 4 days in the lab”, the same is true for filmmaking. Editing and post-production has been a long, slow, and meticulous process. I have been using iMovie to go through my footage and turn it into a viewable film. This software allows me to trim the video clips, arrange and rearrange the clips to be convey a narrative, edit the sound to take out the background noise or enhance the voices, and add subtitles and voice over. My goal is to make a film that is both informative and visually engaging; something that is appealing to both archaeologists and to the general public.

The final version of the film will be released in late 2019. Also in progress are two other short films that were shot during the Burial Hill excavations this summer: one showing the work of the survey crew performing a geo-physical survey of Burial Hill, and one with student interviews of their experiences on Burial Hill. These films, I hope, will allow us to share the Plymouth Project to a wider audience, and show the broader public the all processes of archaeological excavation and the dedicated crew who worked on recovering Plymouth’s early history.