Students and staff from the Fiske Center for Archaeological Research at the University of Massachusetts Boston have recently completed a joint project with the Collections Department at Plimoth Patuxet Museums, funded by the Humanities Collections and Reference Resources program at the National Endowment for the Humanities. This grant created digital catalog records for over 75,000 archaeological objects, now accessible through the Museums’ online collections portal.

The NEH grant, “Digitizing Plimoth Plantation’s 17th-Century Archaeological Collections,” provided the funding for a joint project between the Museum and the Fiske Center to work on four of the Museums’ collections:

- The Winslow site, home of colonial governor Josiah Winslow in the late 17th century (excavated primarily in the 1940s);

- The Allerton-Cushman site, home of Mayflower passenger Isaac Allerton in the 1630s and later his son-in-law Thomas Cushman in the 1650s and later decades (excavated by Deetz in 1972);

- The Bradford II site (excavated by Deetz in 1966); and

- The RM site, home of the Faunce family in mid to late 17th century. Initial processing for the RM site had been done under an earlier pilot grant (from UMass Boston), but the digital access to information about this site and collection was facilitated under the NEH grant.

These four collections were selected because of their research potential, their potential to shape public interpretation at Plimoth Patuxet, and their importance to the history of the development of the museum and historical archaeology, particularly through the work of Henry Hornblower and James Deetz.

Plimoth Patuxet Museums (formerly Plimoth Plantation), in Plymouth, Massachusetts, is best known for its living history exhibits of Wampanoag and 17th-century New England history, but also curates over 50 archaeological collections from the region. Some of these were excavated by the museum’s founder Henry Hornblower in the 1940s; other collections were excavated by James Deetz, a central figure in the development of the discipline of historical archaeology, in the 1960s and 1970s. These collections, which span periods from the deep Indigenous past through the mid-19th century are an important source of information about the lives of the people who lived in Massachusetts. Prior to the start of this grant project, these collections remained in storage, relatively unexamined since their initial processing and research. As the collections were not publicly available online or presented as part of the visitor experience, the only people who knew of their existence were those who worked in the Museum’s Collections Department, or individuals who learned about them through word of mouth. This made it difficult for staff, students, Indigenous communities, and researchers to access these collections. This was further compounded by the fact that some of the collections were relatively untouched since the early 1980s. The collections catalogs ranged from Excel files, to typed manuscripts from the mid-20th century, to print outs of coded information from legacy database formats.

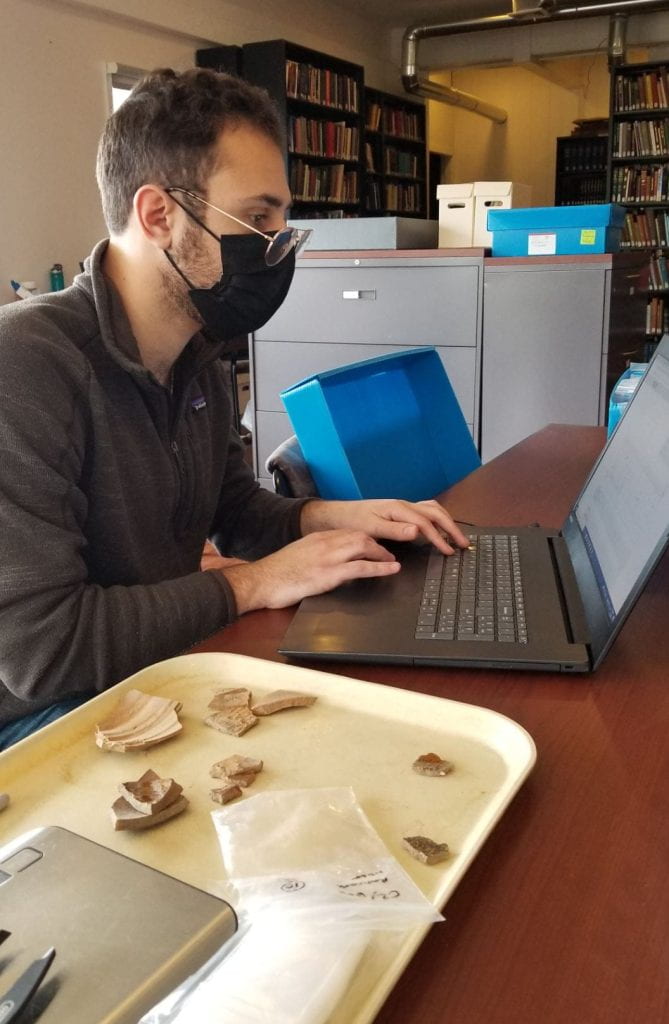

Under the grant, the Museum developed and implemented its first uniform system for processing its archaeological collections. This includes creating digital catalog records in a Past Perfect database; taking digital photograph of each object; rehousing objects in archivally stable storage bags and boxes; capturing provenience information that was in danger of being lost; re-organizing the archaeological collections by provenience so that objects can be easily found for study or exhibit; sharing the digital catalog through an on-line collections portal; and creating site specific web pages with a summary for the general public and links to finding aids and in-depth collections information for scholars.

This process developed with NEH funding is now being applied to additional archaeological collections at the Museum. The development of the Past Perfect database, with both an internal interface for collections management (with information such as conservation status, storage location, and loan status) and a public-facing interface with a simplified view of the database that is linked on the Museum’s website, has been particularly important to the Museum, both for managing its archaeological collections and for improving how collections are presented online.

Site Specific Results

Almost 19,000 digital catalog records and photographs have been created in Past Perfect under this project, describing 75,512 objects related to this grant (20,348 from the RM site; 26,692 from the Winslow site; 3472 from the Bradford site; and 25,000 from the Allerton-Cushman site). This represents the entirety of the RM, Winslow, and Allerton-Cushman collections. The grant work revealed that the Bradford collection came primarily from the mid-19th century and did not have a significant 17th-century component, so it was only partially cataloged. This new information about the Bradford collection is in itself important, correcting long-held beliefs about the date of the site. Re-examination of the collections also prompted additional research into the RM site by the Museum that found past interpretations about who lived there were not correct.

The RM site (C1; Massachusetts Historical Commission Site #PLY.HA.7) is a mid- to late-17th century fortified dwelling house likely lived in by the Faunce family. It is called the RM Site because of a spoon found there with the letters “RM” etched onto the handle, possibly associated with Thomas Faunce’s cousin Remember Morton. Spatially and geographically, it is closely connected to the nearby Eel River Wampanoag site. The majority of the RM collection is 17th- and 18th-century colonial artifacts, with a smaller, but sizable, component of Indigenous artifacts, and some unique early contact-era trade goods. The site also contains many goods of a military nature, such as lead shot, gun parts, and gunflints, along with typical early colonial domestic goods, such as pipe stems and ceramics.

The Winslow Site (C2; Massachusetts Historical Commission Site #MRS.HA.2), located in Marshfield, MA, was the home of Josiah Winslow (son of Edward Winslow) and his wife, Penelope Winslow (née Pelham). Josiah Winslow was the first Plymouth-born governor of the colony, who held office between 1673 to 1680. His probate records indicate that he had a wealthy household: a two story structure with a substantial dairying component with cattle and milk pans. The artifact assemblage reflects the household’s wealth and indicates that the site was occupied in the latter half of the 17th century. The site has a much more substantial collection of stone tools than was previously recognized, as well as a wide range of metal tools, animal shoes, and horse harness components.

The Allerton-Cushman Site (C21; Massachusetts Historical Commission Site #KIN.HA.19) was excavated by James Deetz in 1972 as part of a rescue effort before the construction of a house on the residents’ property in Kingston, MA. Deed research associated the site with Isaac Allerton, a Mayflower passenger, and subsequent generations of his family. The archaeological survey revealed a post-in-ground constructed house dating to c. 1630 to 1650. The house measured 20 by 22 feet, was supported by four large, square timber posts, and enclosed with wattle and daub walls. The Allerton-Cushman site presented the first physical evidence for post-in-ground construction in Plymouth County and influenced the way reproduction colonial houses were built in the English Village at Plimoth Patuxet Museums.

Broader Significance

The Winslow site, the Allerton-Cushman site, and the RM site date to the 80 years following the English colonization of Massachusetts. This was a transformative time period, both for the newly arrived colonists and the Wampanoag and neighboring Indigenous communities. Archaeologists and museum educators are using these older “legacy” collections to ask new questions about colonization and life during this period. In particular, these collections contain many more Indigenous artifacts than previously known, allowing for a more complex interpretation of the interaction between the Wampanoag and the English colonists, and allowing for the study of the continued presence of Wampanoag individuals in the 17th century at sites that have previously been considered exclusively English.

Creating accessible digital information about these artifacts has also enabled their incorporation into educational resources for a wide range of audiences. Beyond their use by scholars of the region’s history and archaeology, the Museum has incorporated archaeological artifacts in online games from children and in teacher training workshops that they have held over the past several summers. The COVID pandemic accelerated the need for digitally-available content from cultural organizations everywhere. The grant work, which began in 2018, was thus very timely and enabled the Museum to more quickly develop and deploy digital exhibits and educational material.

The grant has prompted the Museum to re-think how its archaeological collections are presented online. Previously, no information about the archaeological collections was available on the Museum’s website. Scholars, the public, and Tribal communities had no clear way to learn about the collections held at the Museum. Now, in addition to an online collections portal, the Museum is developing an online exhibit and web sites related to the collections covered in this grant. The digital exhibit will share the knowledge about these collections acquired through this digitization project and incorporate photographs of the objects from the collections, field notes and illustrations from the Hornblower archives. To tie into the Museum’s 75th anniversary, the exhibit incorporates institutional history to tell the stories the role archaeology has played in its exhibits and mission over the decades using examples from the recently digitized collections. The web pages will describe the work at each site, highlight objects from the archaeological collection, and provide links to collections summaries and finding aids for scholars.