William E. Reichman is a physician and chief executive of Baycrest, a leading non-profit elder care organization comprising health care and housing facilities, outpatient services and a research center on one campus in Toronto. His organization operates a 300-bed rehab hospital, a 472-bed skilled nursing facility, 200 assisted living units and 125 independent-living apartments. (Note: In characterizing the facilities, we have used terminology familiar to U.S. readers.)

William E. Reichman is a physician and chief executive of Baycrest, a leading non-profit elder care organization comprising health care and housing facilities, outpatient services and a research center on one campus in Toronto. His organization operates a 300-bed rehab hospital, a 472-bed skilled nursing facility, 200 assisted living units and 125 independent-living apartments. (Note: In characterizing the facilities, we have used terminology familiar to U.S. readers.)

Baycrest, affiliated with the University of Toronto, is also home to one of the world’s largest research institutes focused on brain aging and an innovation accelerator focused on elder well-being. Its tele-education program delivers education content and training to 42 countries around the world.

Gerontology Institute Director Len Fishman recently spoke with Reichman about ways Baycrest has deployed technology to manage the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and how those innovations can permanently influence elder care practice. Fishman is also a board director at Baycrest. The follow transcript has been edited for length.

Len Fishman: A recent Washington Post article reported that 81 percent of COVID-19 deaths in Canada are nursing home residents. How has Baycrest been affected?

Len Fishman: A recent Washington Post article reported that 81 percent of COVID-19 deaths in Canada are nursing home residents. How has Baycrest been affected?

William Reichman: Baycrest has had some sporadic cases of COVID-19, both in residents and patients, as well as staff members who likely brought the virus to the campus inadvertently. I think all told, we’ve had six cases among our 1,100 beds. There have been other senior care organizations in Canada which tragically have had 40 percent or more of their residents test positive for the virus and 25 percent or more actually die from infection. So it’s been catastrophic in Canada.

William Reichman: Baycrest has had some sporadic cases of COVID-19, both in residents and patients, as well as staff members who likely brought the virus to the campus inadvertently. I think all told, we’ve had six cases among our 1,100 beds. There have been other senior care organizations in Canada which tragically have had 40 percent or more of their residents test positive for the virus and 25 percent or more actually die from infection. So it’s been catastrophic in Canada.

LF: When the pandemic hit, you were quoted as saying, “We’re not going to waste the crisis,” and you talked about using technology to overcome the special challenges of COVID-19. What problems were you trying to solve?

WR: Even when there had been no restrictions on families being able to visit, the reality is that many family members have day jobs or may not live in close proximity. Pre-pandemic, social distancing was already a problem. And meaningful activities that truly energize and enrich the resident population were also in short supply in many long-term care facilities, including Baycrest at times. It’s hard to get timely access to medical coverage, particularly in off hours, because it can be quite labor-intensive and time-consuming. I feel that’s led to a lot of avoidable emergency department transfers because there wasn’t adequate on-site medical supervision and coverage. These were pre-existing issues.

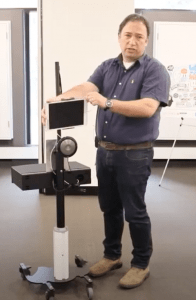

LF: Let’s start with telemedicine. As I understand, at the heart of that effort is the Baycrest T Cart. Describe what the T Cart is.

WR: It’s relatively low-tech. It uses off-the-shelf capabilities like iPads, high-quality speakers and virtual stethoscopes, something we’ve had for quite some time now. We put it all into a single platform that we deliver right to the patient’s proverbial bedside. When we implemented this, it greatly enabled our physicians from wherever they might be to examine their patients remotely. We had always envisioned having that capability. But when the pandemic hit, it became a necessity, not a luxury, so we rapidly deployed this. The point is to deliver it in the most cost-effective way so it can be scaled. If only a handful of organizations do this, we’re really not providing a solution that delivers value.

LF: How many telemedicine sessions have you had so far?

WR: Almost 2,000.

LF: Are you learning what kinds of sessions most lend themselves to telemedicine?

The Baycrest T Cart. A demonstration video of the cart can be viewed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JQHDwj6pn-g&feature=youtu.be

WR: The video capabilities with Zoom features most certainly help a physician in a remote location to examine a patient’s breathing pattern, skin color, mobility. They’re able to do cognitive examinations remotely to see whether the level of confusion has increased. So both the video and audio really do help us to do quite a lot.

We also have remote EKG, stethoscope, ophthalmoscope, so you can look at a patient’s eyes remotely, look inside their ears. We can accomplish quite a bit remotely in terms of the kinds of common afflictions an older person living in these kinds of settings would suffer. You can listen to their chest and see whether they’re wheezing or having difficulty breathing, and the technology gives you all their vital signs, including their oxygen level.

LF: What kind of staff member do you need in the room with the T cart in order for this session to work?

WR: At first, we thought you needed a nurse there. Then we determined what was actually needed was what we’re calling a “clinical liaison.” It can really be anybody who, in relatively short order, can be trained to use the technology – that’s really a critical feature. If there are gaps in what the physicians or the nurse practitioners delivering care remotely are able to understand, they can ask some simple questions, just as if that clinical liaison was a family member.

LF: Could it be the equivalent of a nurse assistant?

WR: Oh, definitely. Generally, the people we’re recruiting have a bachelor’s level of education, which is not the case for nursing assistants. But we’re still trying to determine what are the core skills that are necessary to enable this.

LF: Have you have enough experience to know whether this works for residents with dementia?

WR: We have been using it for residents with dementia and also to assess the onset of delirium. We are able to do a mental status test using telemedicine in ways that we never imagined were really possible. We can detect changes in cognition or mental status that may herald that something medical is going on. In the COVID context, it’s looking for signs of a virus. But in nursing home settings and for older people living at home in the community, they have multiple co-morbidities. So a change in their appetite, a change in their mobility, a change in their mentation could be due to a whole host of things. You have to work your way through the differential diagnosis.

LF: Let’s talk about e-visits. One of the greatest challenges of the pandemic, for both residents and family, is a prohibition on visits. How have you used technology to keep them connected?

William Reichman in recent Zoom interview.

WR: We’re using iPads by and large, because they’re easily mobile. We’ve procured almost 1,000 and distributed them across all of our care settings. We’ve taught families how best to use them to connect with their loved ones remotely and, where our residents have the cognitive ability to be able to use the iPad, they are. Otherwise we have staff members who will accompany the residents while they’re having their evening visits with their family. Just in the past couple of weeks we’ve had a birthday party of a 103-year old with her relatives from all over the place – Israel, the US, Canada.

Again, we’ve had to do this because of the pandemic and visitation restrictions. But this is of great value even when you’re not in a pandemic. If grandma’s in a nursing home but she wants to attend her great-grandson’s bar mitzvah, she should be able to do that virtually. This technology has been around for a long time and we’ve been doing this at Baycrest, but we never scaled it to this level.

LF: Besides connecting residents with family and friends, how is Baycrest overcoming social distancing to perform other forms of social engagement?

WR: Typically, if you’re going to engage in a group activity, whether it’s an arts class or music, you’re physically present with the other members of your group. When the pandemic hit, we escalated our abilities to connect using technology. We’ve taken all of our dementia daycare programs, almost all of our recreational social exercise and music programs, and we’ve virtualized them. We’ve made modifications so everyone can participate remotely. We had to do all of our Passover Seders this way.

Then we created a television station — Baycrest TV. We should’ve done this five years ago. We loaded all kinds of programming on it. Some of it is live and some is pre-recorded video you can access on your TV whenever it’s convenient. We do a lot of that for arts and crafts. We bring a kit into your room and your leader is on the TV walking you through the class. You can see not only the teacher, but also all of your other arts and crafts mates who typically you’re with in the studio.

LF: What has the response of staff and residents been to this pivoting to a more virtual kind of visiting, programming, and healthcare delivery?

WR: I would say at the highest level the staff are pleased to see that a gap has been filled. The staff can see with their own eyes how detrimental it is to the well-being of the residents to be confined to the floors where they live, to not see their family members, not do so many of the things that are important for them to have a reasonable quality of life. The physicians were at first a bit wary that they might not be able to deliver the same quality care. Not every physician has embraced virtual care as effective enough. None of us were trained to deliver healthcare through a monitor. We were trained to hold our patient’s hand.

LF: You’re a geriatric psychiatrist. What observations do you have on the lingering affects the pandemic will have on older people and also on staff at Baycrest?

WR: All of us vary in terms of our resilience, so I don’t want to cast a wide net on all older people. We do know that social distancing leads to enhanced levels of isolation and loneliness, which have negative impacts on physical health, cognitive health, as well as emotional health. But the one thing that gives me confidence is that many of the older adults that I’m responsible for at Baycrest are well into their nineties. They’ve lived through World Wars, they’re now – hopefully – living through a pandemic. These are resilient people by their nature. That’s why they’re still with us.

LF: Is there anything else you would like to add?

WR: I think that as a leader of this type of organization, when you’re presented with lemons not of your own making, you should find opportunities to make lemonade. There are almost always those opportunities. That’s a critical lesson here – as awful and painful as this pandemic is today, some good should come of this. We should take the lessons learned and apply them to do that much better of a job ensuring the well-being of the people that we serve.

Leave a Reply