By: Maor Goihberg

He is in the depths of a nightmare. The sound of a police siren is slowly receding, but his friend’s cry continues to reverberate. The camera pans out, revealing that we are seeing his reflection in the overhead mirror. His friend runs in to comfort him. “I was having a nightmare,” he explains, only to ask in horrific realization “I wasn’t dreaming, was I? I just killed a man, didn’t I?”

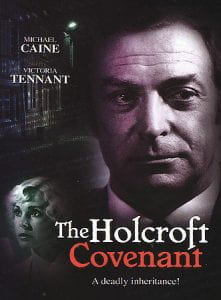

The Holcroft Covenant is not the most well-known film directed by John Frankenheimer. Most critics regard the 1960s as his most prolific period, when just before the emergence of the film-school brats, he helmed pioneering films like The Manchurian Candidate, pushing Hollywood much like Orson Welles did twenty years earlier. When people think of his post-sixties work, the only film that tends to come to mind is Ronin.

But I would argue that at this point in the mid-eighties, Frankenheimer was undergoing a creative revival. The following year he released 52 Pick-Up, an Elmore Leonard adaptation starring Roy Scheider. That was an extremely tense crime film, depicting Los Angeles through the lens of a man navigating the seedy underworld. What I found that these two films have in common is an investment in style, not as a distraction from the events depicted, but to deepen our stake in them.

The film is also an adaptation, based on a novel by Robert Ludlum. The story centers on Noel Holcroft (Michael Caine), a New York architect who, as it turns out, is the biological son of a Nazi general who committed suicide during the Allied invasion. He is called to Switzerland to meet with a banker, who tells him that his late father and two of his comrades turned against the cause, stole money, and are storing it in a Swiss account for a time when their children could use it to repair the damage caused by the war. As his only son, Noel is responsible to oversee such efforts.

While this [the plot] may be clear-cut, what really caught my attention is how Frankenheimer directs this exposition-heavy scene. On the ferry where they are speaking, a man is following them. A spectacular deep-focus shot captures the man hovering from above on the observation deck while they proceed forward in the foreground; indeed, even in subsequent shots where the camera’s movement pushes him out of frame when tilting back, he remains in the same position, a threat that persists.

When they got off the ferry, a second man approaches them concealing a pistol. The first man notices him, and the latter sends him a signal, and a third man enters the mix. They end up following one another in a row, slowly approaching our protagonist. The fact the first man has also prepared a pistol suggests that they will both shoot Noel; however, when the second assassin unveils his weapon, the first shoots him, stabs the third, and walks away. On his way, he stops and gives Noel a nasty stare. Noel asks, “what happened?” to which his colleague shrugs, “who knows? The world is full of lunatics shooting at each other in the streets.”

Here we are exposed to the film’s underlying nature: a labyrinth, a world put off-kilter. The villains in Candidate or Pick-Up may have permeated insanity, but they followed a clear line of thinking. Here, however, insanity is the norm these characters follow, a warped universe built to test Noel.

Nothing better demonstrates this than the sequence in Berlin. There’s some sort of parade taking place honoring the city’s prostitutes (“you need a date for orgy later?” one inquires); somehow, Noel and his confederate Helden are allowed to walk through it. A guy wearing a fishnet over his face punches Noel, while the hitman from earlier kidnaps Helden. Noel chases after her, ending up in a brothel where women are being rotated on a mini-Ferris wheel. An agent stops Noel, and Frankenheimer stops the film to show him teaching Noel how to use a gun, before resuming the chase.

The film owes more than a little to Fritz Lang’s Ministry of Fear, which also depicted an ordinary man trapped in a nightmarish world of Nazis. But this is something else, perhaps even scarier. Near the end, Noel and his ally Leighton return to their safe house, where they find their boss and Noel’s mother dead. The murderer painted swastikas over the walls in blood, growing like spores; Leighton goes up the stairs to the second floor, while Frankenheimer cutting to Noel moving a bit closer in that direction. After a moment, however, Leighton comes down the second set of stairs from behind, finding nothing. It’s such a perfectly warped reality, almost expressionist in places, from which Noel can find no escape, except to adapt.

Early in the film, Noel was in his apartment, listening to his messages. As he is doing so, he is standing next to a large mirror, itself reflecting a mirror on the other side of the apartment, thus giving us three Noel’s in one shot. In that hotel room in Berlin, we only saw two, and at the end, there will be no mirror: just the man who survived the test.

I’m a big fan of Frankenheimer (my favorite of his films being “Seconds”) but I have never seen this one. Now I want to —the Lang reference piqued my curiosity…

Nice review!