Pontypool movie poster

Words have power. They can infect the world with notions, ideas, concepts. It brings with it understanding. And zombies.

Words and language are the key to our entire human evolution. To communicate, share, command, control, question, create – all are enabled by speech. This world of words has long since expanded into the world around us, growing into images, then print, sounds and images moving on the airwaves, bleeding into the pervasive media environment all around us. In 1964, Marshall McLuhan, said “The medium is the message because it is the medium that shapes and controls the scale and form of human association and action.” (from Understanding Media, p11). Often, when we take in a message, we give no thought to the medium in which it is transmitted. That oversight can cause us to miss a lot of context that perhaps would serve us well to observe. It is not an oversight made by director Bruce McDonald in his 2008 intelligent horror-thriller, “Pontypool”. Based on the book “Pontypool Changes Everything” by Tony Burgess (who also wrote the film adaptation script), it is a treat for those who like to get meta, Pontypool really dives in.

(note: I try not to be too spoiler-y, but the analysis might be considered so….just in case that is of concern.)

The intro sets us up with the typography of the title revealing the word “Pontypool” piecemeal, first highlighting the word “typo” that is centered in the name, a clever little visual that foreshadows all to come. Set in a small town Canadian radio station, the story introduces us to Grant Mazzy (Stephen McHattie), a former shock-radio host exiled to this smaller, rural existence. Moments before he arrives at work, a strange run in was had with a distressed woman muttering what subtitles reveal as the word “blood” over and over, appearing confused before vanishing into the early morning darkness. Grant takes this as a cue for listener call-in response to “when do you call 911?” as he works his way into his usual fiery rhetoric. His high-key hype style is both engaging and ridiculous in light of the needs of this community of Pontypool, where his daily broadcast features the obituaries, school closure reports, and appeals to find a lost cat named Honey. He has two coworkers present: Laurel-Ann (Georgina Reilly) the intern, and the producer of his morning radio show, Sydney (Lisa Houle). Ken (Rick Roberts) is another voice that shares Grant’s airwaves, delivering to us the weather and traffic news of the day…at least until things get a little curious under the watchful eye of the “Sunshine Chopper”.

Suddenly, in this small rural community, there seems to be something dramatic happening nearby. A riot seems to be happening at the offices of a Dr. Mendez (Hrant Alienak), cause unknown. Ken becomes frantic, really leaning in to the trope of the terrified reporter in the face of monstrosity, speaking of trampling, of blood, even exclaiming that there seemed to be “…an EXPLOSION of people!!”; it isn’t long before BBC News is on the line to speak with Grant as the radio persona who broke the story. Is there a quarantine? Are the roads blocked? Is this a conflict between the French-Canadians and those who speak English, a racially motivates “insurgency” of terrorism?

Grant the shock-jockey at work

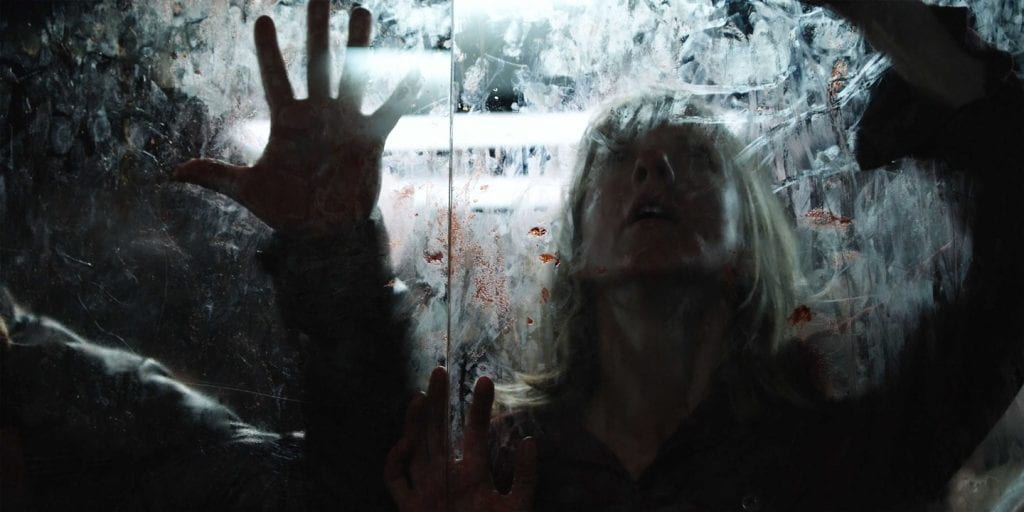

Grant is visibly shaken and begins to waver in his thoughts. Is this even REAL? Is he being punked? If it is real, what is really happening? Grant tries to wander off, and his stunned demeanor seems a bit like what we could imagine PTSD looks like, manifest in a former soldier having a flashback, as he insists that he “has to see for himself”, heading outside. This is going to be a theme that plays out for the duration of the movie – moments where Laurel-Ann responds like a grunt under orders hints to us what this is about, as did an earlier scene just before the chaos ensued in which we see locals in a hokey singing group, dressed as “Arabians”, with one little girl in full on blackface and reference to Osama bin Laden and terrorism laid on thickly. Grant has on his thinking cap, and those gears are turning, hard. He witnesses the zombies, and we hear about the insanity and the cannibalism, though we as an audience are subjected to very little direct violence, as the story grows frantic, with the horror implied but never shown. There is copious blood being…ejected…from the zombies, however. Oh yes, this is real. But WHY is this occurring? Dr Mendez himself shows up on cue, to explain to us in his mad-doctor manner that this zombie disease is spread by words. Specifically, English, with particular infectives being terms of endearment and “rhetorical discourse”. Again we think, why? “It makes no SENSE!” declares Grant…and then it hits home, the uncomfortable and deeper truth – that’s it! TRUTH! Grant had complained of the BBC creating chaos with incorrect conjecture of terrorism, he reflects on the military doing it’s job of killing citizens outside who are infected, and he realizes that it is very possible that HE is a huge vector of the plague. Himself, the BBC, media, speaking their words of half-truth for drama and effect, media not doing due diligence in getting the facts before broadcasting. The medium IS the message after all, and it is a vector of disease. Words want to be spread around, one person to another. News travels fast. Mouth to mouth, it is when we understand the content of the messages that we become infected with words, be they true or false. There is quite a lot of conjecture and semi-philosophical discourse on the nature of words and language for a horror movie that follows. Grant works out a “cure” by literally redefining the words as we understand them, releasing the hold it had on them, even as the military circles overhead, ready to treat them as the enemy. “KILL is KISS” he tells a distraught Sydney. Once more Grant exclaims something to the effect of “…of course it makes no sense! It never did! YOU ARE KILLING PEOPLE WHO ARE SCARED!” even as the story is still being spun, this time by the military, and a flat-out lie.

It is worth noting that the set of the movie is set solely in the radio station, and at times looks like a stage play while sounding like a radio drama (indeed, there is a BBC radio drama of Pontypool as well). It is simple and well staged in the space of the studio, building dread slowly even as it keeps visual violence to a minimum while still holding tight to that “zombie essence” as a trope. It was done on a tight budget and they did well by it. The slow build of anxiety from knowing something is very wrong, but having no idea exactly what that something is, is expertly played. The metaphor that sneaks in about the dangers of overly enthused newscasters throwing false leads out there and spreading fear, spreading this embodied disease, enabling more fear and terror as the military responds is haunting.

This is a horror movie that may miss the mark for genre fans who prefer their monsters to be more literal and explicit, but it is also a horror movie that I love introducing to people who hold no love of horror but do like a movie that gets the gears moving in the skull. Pontypool took me by surprise, and left me with plenty to think about to boot.

Let us in, Grant. We just wanna talk to you….