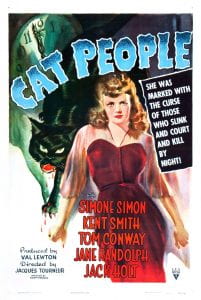

Cat People Poster

Cat People is an extraordinary classic. It was a slow-burn hit in 1942, and became a beloved cult movie, and one often discussed in Cinema Studies. There is a rich tapestry of visuals and messages contained within it, and every moment of its 73 minute runtime has been devoured and digested, from dialog, to lighting technique, and through its unique and stunning editing. Rich with unspoken context, most especially sexual tensions, there is much to delve into within the movie’s use of archetype, psychological ploys, symbolisms. The movie owes much of it’s depth to the use of darkness and the shadows, where the dread of the audience’s imagination lies in wait. Yet, even when we look, we find less than expected and yet, this emptiness only builds upon itself, giving ample room for our minds to fill it. Despite this volume of topical dissection and analytical examination, the Cat People holds a tone of mystery that continues to beckon to each new generation that discovers it, calling them to explore the darkness. And we heed that call because, as Irena (our protagonist) says, herself says – “I like the dark; it’s friendly.”

Cat People was a success of Val Lewton, made on a budget of $135,000, and brought together some extraordinary talent in the process – direction by Jacques Tourneur, cinematographer Nicholas Musuraca, scripting by DeWitt Bodeen and a plaintive score by Roy Webb. The movie was a production for RKO that led him to have a continued run of films that followed Cat People over the next four years through 1946. An experienced screenwriter and story editor himself, he learned his art under producer David O. Selznick of MGM. Lewton wasn’t without some of his own shadows however – he had some interesting sidelines of work before his success with Cat People, writing trashy pulp novels and other “morally questionable” activities, published under pen names. But his time with Selznick paid off, and his break with Cat People gave him a path in which to shine in Hollywood.

The story unfolds thusly: Irena Dubrovna (Simone Simon), a Serbian artist in exile, has been cursed. The Balkan curse extends to all the women of her village – that those very women will metamorphose into a panther if they should become passionate, and this forms the basis of her deep fear of losing control over love. This prevents her from making a true connection with the man she loves, Oliver Reed (Kent Smith) out of fear these stories have created in her. We of course, perhaps have a little laugh at the absurdity of such folk tales, as do others within the film, notably, her psychiatrist, Dr. Lewis Judd (Tom Conway). She finds her concerns brushed away as mere superstition, or even trauma. Yet even so, there we see the myth hinted at in something as simple as the reaction of panic shown by birds in the pet shop at her arrival as the owner remarks that the animals are “ever so psychic”.

Cat People also toys with themes of sexuality and the contexts of it within marriage (and later, suggestions to the allusion of lesbianism as well), purposely poking a sleeping beast that existed within the Production Code, a system by which any sexual content, even hinted at, could be redacted for fear of corruption of the wholesome American audience. Her “otherness” is highlighted as well, her non-American status as an immigrant, creating a feeling of separateness in the differences between her “mysterious” and witchy ethnic background and Oliver’s all-American cheer, deepening the obvious chasm between them. They initially encounter each other at the zoo and introductions are made – he is a draftsman for a shipbuilding company, and she is an artist, who happens to be sketching a panther…impaled upon a sword. Curious, no? Already, there are shadows overhead.

Irena explaining the Tale of King John to Oliver

They meet and soon thereafter are married, surprisingly, if we consider Irena’s pathological fears and Oliver’s blithe cluelessness. Deeper and more ominous details are revealed about Irena – that the curse she believes she bears is because of devil worship in her ancestry, which was nearly erased by “King John”, which Oliver glosses over in his usual manner, with assurances of her “normalness”. At their wedding dinner, Irena encounters an exotic woman who greets her as “sister” in conversation, setting off some suggestiveness in the process. We never see her again, but that moment changes the tone of the film. Henceforth we bear witness to Lewton’s touch over and over – fleeting impressions giving us the tale in symbolic and predictive snippets- Irena’s predictive sketch drifting away on the wind, howling of beasts near her, shadow outlines of a crouched Irena by the window and then again in the shower (a racy moment for the age, with her bare skin glittering with drops of water)…or the moments where she brings the zoo panther a bird to eat, dead in her hand. The visual shifts that occur from scene to scene share a distance spoken of by Oliver as he states “in many ways we’re strangers”, even as we watch the rift grow. Though the film is in black and white, there never seems to be any truly bright or sunny moments in the film; instead there is a slight dimness to the lighting of the day scenes, as though overcast.

After a long run of being reminded at the disintegration of Irena and Oliver’s relationship, we finally get to the metaphysics of the tale, the dark center towards which we have been sauntering. The greyness of daylight hours blend into the darkness of the night, a fitting transition after the time we have spent witnessing Irena’s torment, mistrust, and depression, laced with yearning and loneliness, or Oliver’s willful ignorance combined with his increasing frustration at Irena’s inability to consummate their marriage. Oliver’s shallow emotional depth seems to come to the fore as we see his frustration turn to flirtation with his office mate Alice (Jane Randolph) far too easily, even as he confesses “I’ve never been unhappy before”, continuing on about how easy his life has been until this conundrum had occurred. In this moment, Oliver’s innate lightness paired against Irena’s brooding torment is stark – he is the American dream embodied, she is the broken influence of foreign destructive forces, lurking in the shadows. He encourages her to seek help, from a psychiatrist that was written to be despised, Dr. Judd. He is slick and suave, and also dismissive and immoral in his authority. He explains the deleterious effects of childhood trauma, leaning into Freud as he informs us that the death instinct lurks in us all. That Freudian allusion leads neatly into his lecherousness that makes itself known at first opportunity. Needless to say, it doesn’t end well for Dr. Judd.

We continue to see Lewton use crafty obfuscation throughout, saying everything with literally nothing in the key scenes. Alice is followed by Irena in the park, an implied stalking with each moment of ceased footstep or pause to scan the area as the sense of being watched tingles in us, or the famous moment in the pool scene where moviegoers SWORE they “saw” a panther in the shadows, even as there was nothing to be seen at all on screen, beyond the implication itself. Yet the follow-through indicates our raging imaginations were onto something – paw prints blend into shoeprints, a terry cloth robe was torn to shreds, as though by a large cat. We recall the rustle of a bush, the growl we may have heard in the shadows by the pool. We make assumptions naturally, that Irena is indeed manifest in the form of a giant cat, yet we see not one single shred of tangible evidence that this is so. Budget concerns may have necessitated this wonderful play of tensions against our imaginations, but in truth the effect of not seeing what we know to be there is raised to a fine art in drawing out our tensions, with breath held a moment too long, as we wait for a creature that never shows up. It is a glorious trick, a tease that truly gives depth and tone to the plot.

“I like the darkness, it’s friendly”

In the end, Cat People tells us a tale as modernized myth, wrapped in a bit of horror, to impressive effect. There is no clear cut evil within the tale, nor shining knights for good – all the players are of mixed character, intermingled well. There is deep expression of tragedy and sorrow under the horror and dread presented in the protagonist, and even the cheery persona of her counterpart contains a search for companionship and longing to not be alone. We are not left with the expected “bad guy” on who we may place blame – Irena was a mere pawn of fate, having inherited a punishment for a sin she did not commit. The movie as a whole carries a gothic shadow overhead, a pall of death as an eventual fact that is closer than we may think, which may have struck a deep chord in the wartime audience to which this movie played originally. It carries us away into the darkness, with the “friendly” promise of oblivion and escape from the grief and sorrows that may plague us, as they do the characters of this story.

I love the choice of this film and reading this makes it clear it is a perfect film to view in these times. As you say, “There is no clear cut evil within the tale, nor shining knights for good – all the players are of mixed character, intermingled well.”

It is such an absolutely GORGEOUS film. Irena always stirs such empathy from me. I’m always so impressed that the act of never showing us the monster in action was born of a budgetary choice and became a hallmark that really sets this movie apart, as well.