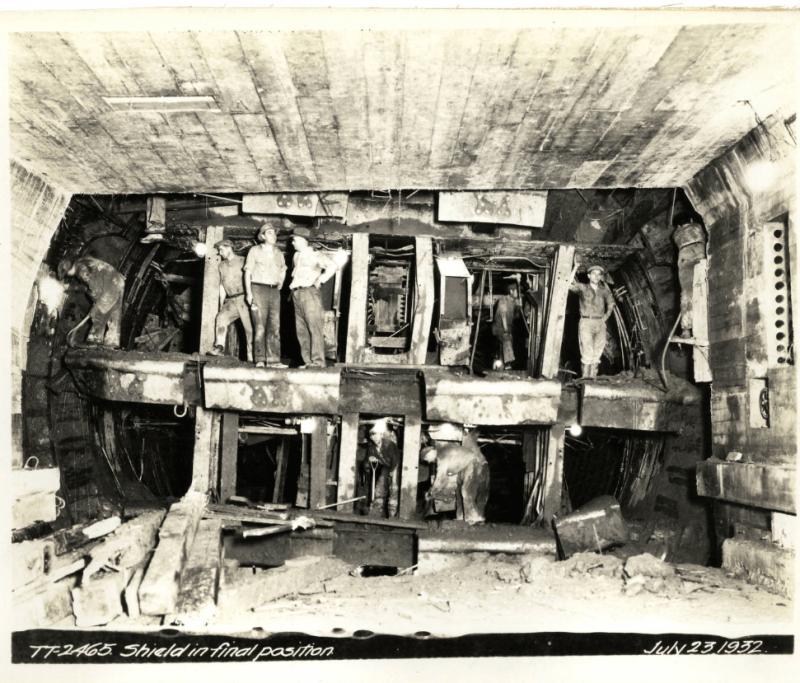

“Shield in Final Position.” Here is the Sumner Tunnel tunneling shield in its final position after breaching the Boston Vent Shaft. Presumably, that means it was all set and ready to start digging under Boston Harbor. These men were standing at the back of the shield. You can see how the tunnel was constructed behind it as the shield moved on.

Author: Kayla Allen, Archives Assistant and graduate student in the History MA Program at UMass Boston

Our Sumner Tunnel collection consists of a fascinating set of photographs and papers. It doesn’t only offer us information about the Sumner Tunnel. It gives us a visual understanding of underground and submarine construction work. It shows us the economics and geography considered in the 1930s improvement of Haymarket Square. It lets us peek at the architecture of Boston at the beginning of the twentieth century. Many of these compelling photographs show us extant and extinct buildings, ranging in location from Haymarket Square up to Clark Street. Other photographs give evidence of the different kinds of supports that buildings and streets needed while the tunnel was being constructed beneath them. Still more show Boston’s streets with a bird’s eye view.

My favorite pieces of the collection show the construction of the tunnel and buildings related to its use. When I started writing this blog post, I had no clue how underwater tunnels were created. Through research, I learned that the Sumner Tunnel was created with something called a tunneling shield. This is a cylindrical piece of machinery inspired by a type of boring worm. Mechanical constructions push the large tube through dirt, soil, or sand and create a pathway. Workers mine the dirt that comes in from the holes in the flat shield at the front of the tube and place supporting structures in the tunnel behind the tube as it moves. Compressed air at the front of the tunneling shield helps to make sure that the tunnel doesn’t collapse (1). With our photograph collection, we get a strong idea of how this worked for the creation of the Sumner Tunnel. We’ve included some photographs of the Sumner tunneling shield at the end of this post.

I was also intrigued by the photographs of the construction of above-ground buildings. Our collection shows the origins of the Traffic Tunnel Administration Building at the very end of the tunnel (where they originally started digging) and the North End Sumner Tunnel Ventilation Building between Clark and Fleet Street. The photographs show the process of constructing the Administration Building and give us a peek at the tunnel’s exit. They also show the tunneling shield entering into a large rectangular concrete vent. After the shield moved on towards the Harbor, workers built a structure over that vent that pumps poisonous air out of the tunnel and fresh air in. This building is still in use today, and you can see it as you walk along North Street.

Be sure to check out the collection and its finding aid. I’m sure that they will inspire you to learn a little bit more about our incredible city! If you’d like to learn more about the Sumner Tunnel as it is today and its upcoming centennial restoration project, click here.

All images shared here are courtesy of the University Archives and Special Collections Department, Joseph P. Healey Library, University of Massachusetts Boston: Sumner Tunnel (Boston): construction photographs.

References

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Tunneling shield.” Encyclopedia Britannica, May 11, 2011. https://www.britannica.com/technology/tunneling-shield.

![SC-0137_IV_f1_001 Southwest Corridor Project. Relocated Orange Line/railroad improvements, [1977]](https://i0.wp.com/blogs.umb.edu/archives/files/2015/10/SC-0137_IV_f1_001-1w0gf1v.jpg?w=94&h=155&ssl=1)