Author: Amanda McKay, Archives Assistant and graduate student in the English MA program at UMass Boston

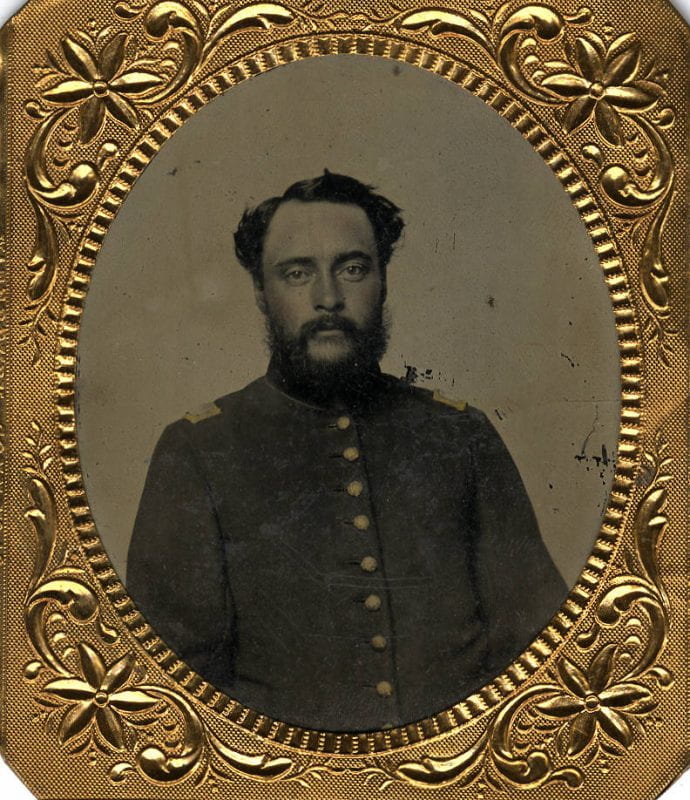

Growing up in and around housing projects in Roxbury, Massachusetts, Jack Powers was no stranger to struggle and need. At the age of seventeen, Powers decided he was going to turn this struggle into something good, and the rest of his life is a testament to his devotion to community, welfare, and knowledge. Healey Library’s Jack Powers collection highlights the various areas of activism that Powers belonged to. Two major accomplishments from this collection are the Beacon Hill Free School and his Stone Soup poetry reading series.

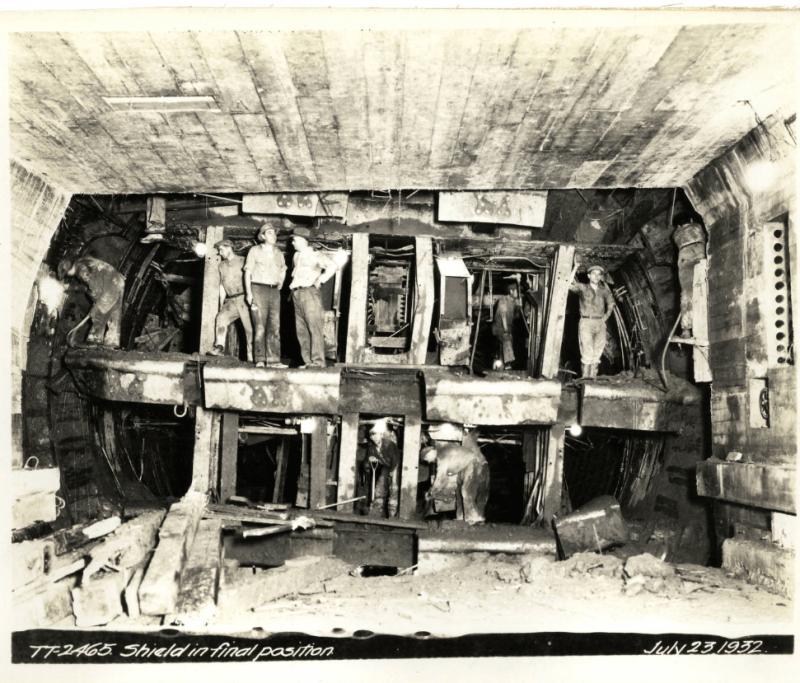

During the prime of the Beacon Hill Free School, weekly classes on various topics were held for local community members, free of charge. Holding around eleven classes per week in his apartment, and another twenty per week in the Beacon Hill community center, Powers had a full schedule—and he never sacrificed his philanthropy for paid work. Class topics were not limited by any means, with Powers saying, “Every idea was held up like a jewel in the light so that if there were any defect hopefully human intelligence would see it” (Robb 2 Jun. 1979). His idea of freedom was expressed through the catalogue of extensive classes that were offered.

Later, in the 1970s, Powers decided to create Stone Soup, a nightly poetry event. Stone Soup was a come-one-come-all event that featured renowned poets such as Allen Ginsberg, as well as local poets who hadn’t gotten their break into the spotlight yet. True to its name, a children’s folktale about community, the poetry series was a collective energy that livened up the arts scene in Beacon Hill and in Boston as a whole. Powers once said that, “We’re all in this world together, and there’s no better way to translate pleasure than through the magic of words,” showing his true intentions behind the reading series. Accessibility was at the forefront of Powers’ mind, and he achieved it by creating a safe space that was less “literary salon” and more “neighborhood activism.” Stone Soup lives on today, with meetings held both virtually and in person. There is an updated blog page with recent and upcoming activities that the organization holds as well as spotlights on local authors and artists.

The Jack Powers collection at UMass Boston not only includes information regarding the programs that Powers founded, but also information about Powers’ personal life and writings. The collection isn’t just about the power of art, it also documents the power of community and what can happen when people come together, something that must be remembered and held onto for generations to come.

All images courtesy of the Jack Powers collection in Healey Library.

References:

Hartigan, Patti. “Literary Boston: Literary Boston.” Boston Globe. February 16, 1989. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/literary-boston/docview/2445561348/se-2.

Holder, Doug. “Stone Soup Poetry founder Jack Powers: Looking back.” The Somerville Times. October 27, 2010. https://www.thesomervilletimes.com/archives/8821.

Jack Powers collection, SC-0001. University Archives and Special Collections, Joseph P. Healey Library, University of Massachusetts Boston. Accessed August 1, 2025. https://archives.umb.edu/repositories/2/resources/195.

Negri, Gloria. “Boston’s Jack Powers: Helping people body and soul.” Boston Globe. March 15, 1987. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/bostons-jack-powers-helping-people-body-soul/docview/2074430383/se-2.

The Poetry Foundation. “Jack Powers.” Accessed August 1, 2025. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/blog/uncategorized/55706/jack-powers-.

Robb, Christina. “A Poet’s Odyssey with Stone Soup.” Boston Globe. June 2, 1979. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/poets-odyssey-with-stone-soup/docview/747069726/se-2.