Author: Maci Mark, Archives Assistant and graduate student in the Public History MA Program at UMass Boston

Happy Black History Month! Black History Month is celebrated during the month of February every year as a way of celebrating important people and events from across the African diaspora. Here at UMass Boston, we have many collections about the Black history of Boston and our campus. Over the course of the month, we will be highlighting some of these collections and stories.

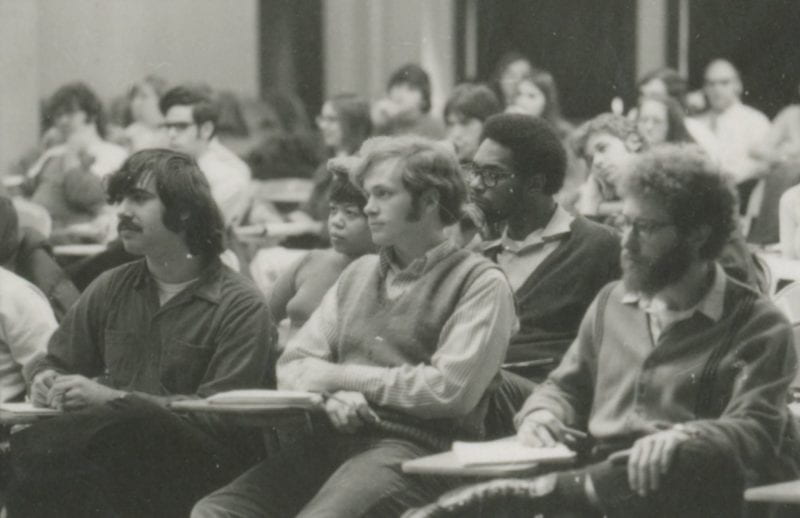

First founded in 1964, the University of Massachusetts Boston was created to serve the urban population of the City of Boston. UMass Boston was envisioned as a place of education for underserved communities, and to support working class students, first generation students, and those that could not afford the elite private schools which made up the educational offerings in Boston. UMass Boston has served these communities for more than fifty years, including the Black community of Boston. Black students have always been a core part of the campus community and have fought to make change and feel represented on campus.

Only three years after the university’s establishment, by the 1967-1968 academic year, UMass Boston had 100 Black students out of its 2,600 student population. While 26 Black students out of every 100 is not a lot, especially with the university’s goal of supporting urban students (which at the time meant thousands of Black students), this actually made UMass Boston one of the most racially diverse schools in the country at the time.

Black students on campus quickly formed the Afro-American Student Association to find community and advocate for their needs on campus. The students in this organization, led by Alvin Johnson, led protests and staged a sit-in at the 1970 summer class registration to demand the hiring of more Black tenure-track faculty and more Black students admitted to the university. At this time there was only one Black tenured professor on campus, James Blackwell.

Despite being the first and only Black tenured professor on campus, Professor Blackwell had a big impact. He was an early advocate for a Black Studies department on campus, which was established as the Afro-American Studies Department in 1973 (currently the Africana Studies Department).

The advocacy did not stop in the 1970s. The William Monroe Trotter Institute for the Study of Black Culture was founded in 1984. This institute allowed for further research and study into Black life and culture.

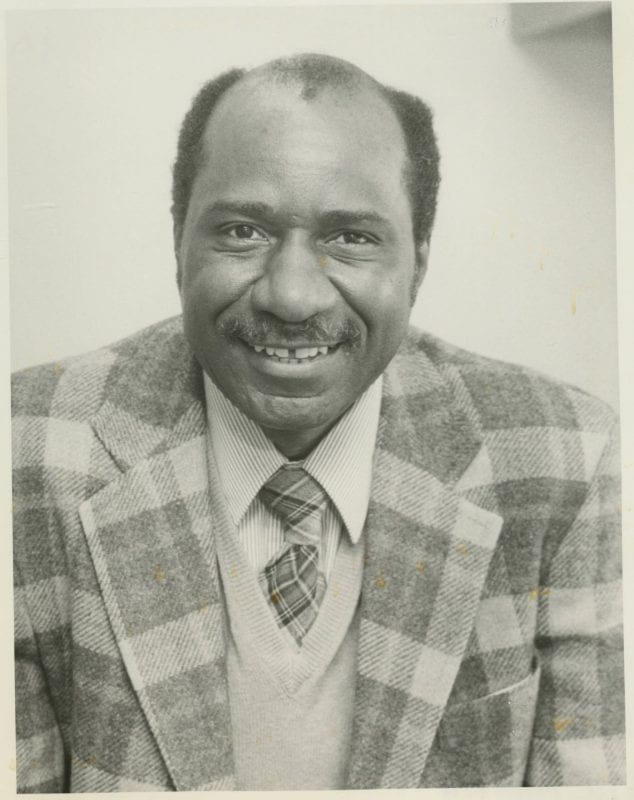

Dr. Harold Horton, the first Associate Director of the William Monroe Trotter Institute, circa 1984-1989

The work that Alvin Johnson started with the Afro-American Student Association in the 1970s continues with the many cultural community groups for Black students that exist on campus today to help students find community and advocate for themselves, including the Black Student Center, Haitian American Society, African Students Union, Ghanaian Student Association, and the UMB NAACP Campus Chapter.

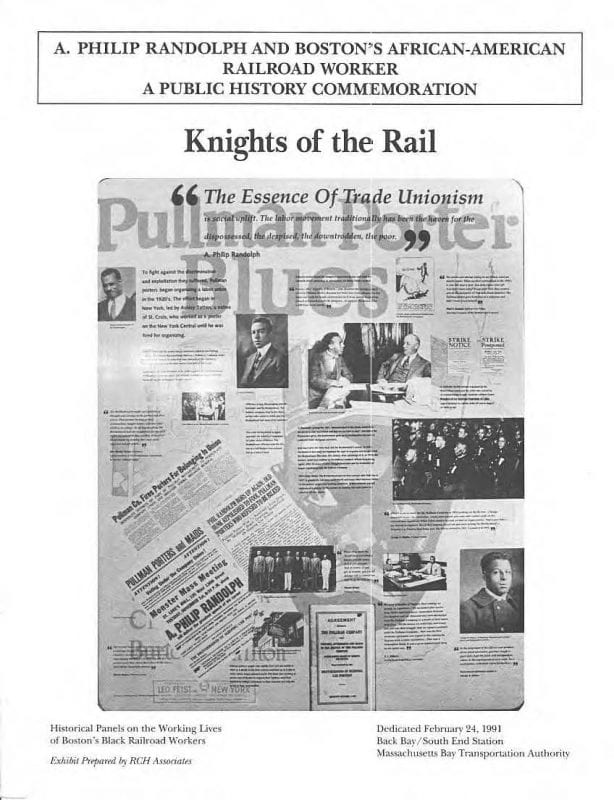

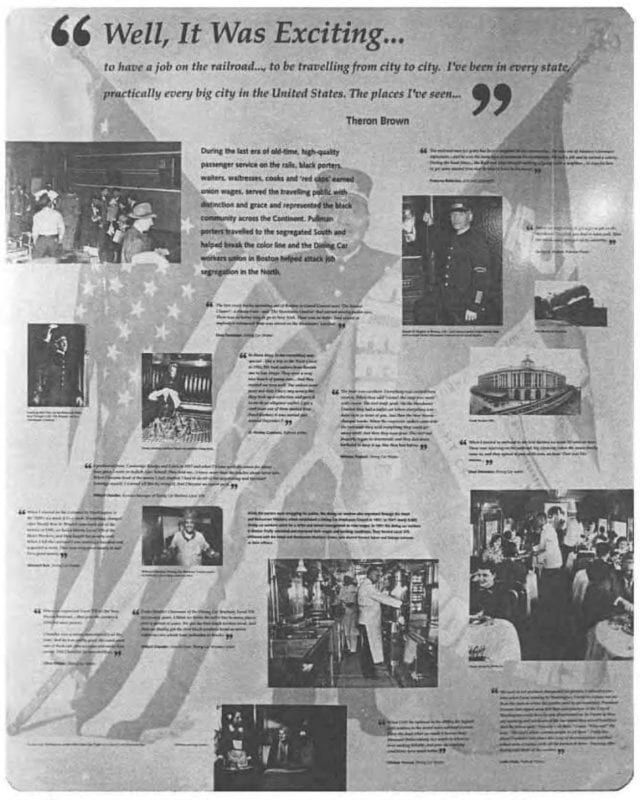

University Archives and Special Collections works to have engaging collections that reflect the history of Black Bostonians and Black students at UMass Boston, including (but not limited to) the recently-donated Mel King papers, the Theresa-India Young papers, the Massachusetts Hip-Hop Archive, the Reverend Edward B. Blackman papers, and the Robert C. Hayden: Transcripts of oral history interviews with Boston African American railroad workers. Check out these collections to learn more about the Black history of Boston. To learn more about the history of UMass Boston, check out UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston by Michael Feldberg.

References

Feldberg, Michael. UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Boston: UMass Boston, 2015.

University Archives & Special Collections in the Joseph P. Healey Library at UMass Boston was established in 1981 as a repository to collect archival material in subject areas of interest to the university, as well as the records of the university itself. The mission and history of UMass Boston guide the collection policies of University Archives & Special Collections, with the university’s urban mission and strong support of community service reflected in the records of and related to urban planning, social welfare, social action, alternative movements, community organizations, war and social consequence, and local history related to neighboring communities. To learn more, visit blogs.umb.edu/archives.