Author: Kayla Allen, Archives Assistant and graduate student in the History MA Program at UMass Boston

Mass. RAR, Inc.: The First 5 Years, 1985 February 19. This video is an excellent summary of the work that Rock Against Racism did from 1979 to 1985. It shows news clips, different RAR performances, and interviews with RAR leaders, including Reebee Garofalo, Fran Smith, Mackie McLeod, and student leader/producer Trae Myers. Some of the clips also include footage from “But Can You Dance to It?,” recordings from break dance crew performances, and sections from a remake of Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” music video.

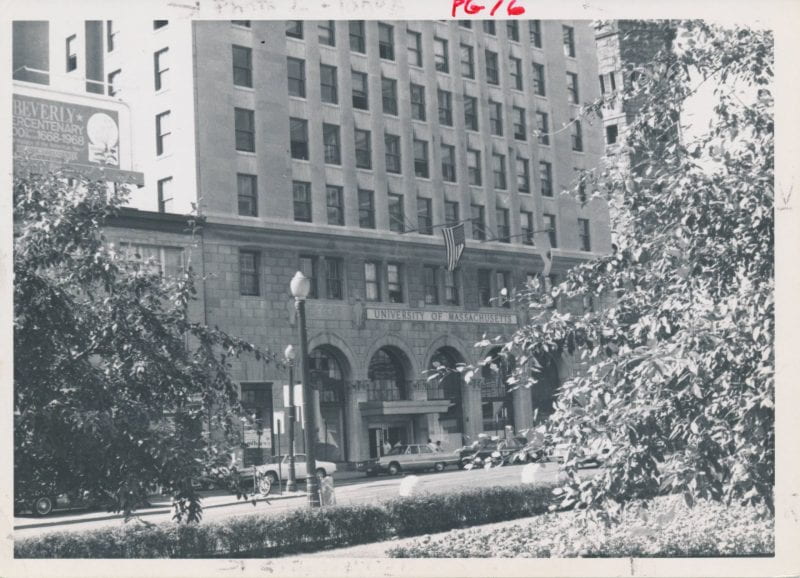

One of our digital video collections is from a group called Massachusetts Rock Against Racism (RAR). Back in the late 1970s and 1980s, this organization formed in order to address racism in the Boston community. Founders and leaders from RAR felt that popular music could transcend boundaries and bring people together, no matter how different these people were. Adults formed the organization and then brought it to Boston youth, specifically high school students. They held festivals where students and adults performed all kinds of music including rap, reggae, rock, and Latin. The festivals also featured break dancing and speeches from local officials and activists, including Mel King. In addition to these concerts, RAR worked with students to create variety shows at their schools and to script and produce a TV show called Living in a Rainbow World. RAR broadcast all of these shows. The leaders of the organization hoped that not only would students get to express themselves and reach across racial divides in the program, but they could also gain valuable workforce skills by being actively involved in the production and broadcasting of their work.

Footage used in Madison Park Rocks, English High All the Way Live, and the Jeremiah E. Burke Jam, 1984 March 18. Here are clips from three of the Rock Against Racism productions in Boston high schools. These include news clips with people like Donna Summers as well as a diverse group of students dancing, rapping, and singing.

In our collection we have final and unedited footage of these broadcasts, including several episodes of Living in a Rainbow World, three of the RAR Youth Cultural Festivals in Jamaica Plain and elsewhere in Boston, and variety shows from different Boston high schools. In addition, we have digital video of interviews with the leaders of RAR such as Reebee Garofalo, Fran Smith, Dan Richardson, Mackie McLeod, and student leader Trae Myers, as well as footage from professional concerts like the “World of Difference” Rock Against Racism television special, and from a one-time music and dance program called “But Can You Dance to It?” We also have videos featuring related people and organizations, including Project Aries (a similar program in Charlotte, North Carolina) and Karen Hutt (a woman working with the Business Connection, a youth entrepreneurial development program in Cambridge).

World of Difference television special, 1985 July 26. This is a Rock Against Racism concert and television special that aired on WCVB Channel 5 on July 26, 1985. Performers included the Red Rockers (rock), the O’Jays (R&B), the Rainbow Dance Company of Boston (modern/lyrical dance), Livingston Taylor (singer-songwriter/folk), and George Benson (jazz, funk, soul, R&B). The production also includes interviews with people such as Reebee Garofalo, Natalie Cole, The Fools, and Al Jarreau.

To see the rest of this footage, take a look at our digital collection and its finding aid (which includes descriptions of all the other RAR documents we hold in the UASC). To learn more about the Massachusetts Rock Against Racism program both then and now, check out their active Facebook page.

Let me know if you stumble across the footage of five young boys dressed up in matching outfits, singing and dancing to “El Coquí (Merengue)” by Carlos Pizarro (hint: they performed at the second Youth Culture Festival).