by An Tran

An Tran is a double major in finance and psychology from Boston, MA. An notes that she came from an “underfunded elementary school” where “the curriculum has been rooted in standardized tests, and preparing for them in order to bring in funding.” Given that, she argues that “our value, as students, has become less about the investment of an upcoming generation and more about how much money we could bring in from our test scores.” An notes that the five-paragraph essay “is a core component of this pattern, and it hinders students from truly learning the craft of writing.” She writes leaving behind the five-paragraph essay structure was freeing, and that she “wasn’t suffocated and forced into a mold or to write in a certain way.” An is passionate about people: she loves writing to create an experience for someone else and to bridge a connection with others. An also writes poems for others in Boston Common in her free time.

When forced into using the same writing strategy over and over again, could students learn how to become better writers? Shirley Rose, a professor of composition at Arizona State University, has developed a theory that writing is a continual learning process, in that each writing context has something to teach you. From Rose’s theory, the answer is a resounding no, students do not become better writers simply practicing the same strategy. As Rose states, “[the] same writing habits and strategies will not work in all writing situations. There is no such thing as “writing in general”; therefore, there is no one lesson about writing that can make writing good in all contexts” (60) With all writing situations being unique, it is impossible to have the same strategy be tailored for every possible scenario; a one size fits all solution won’t cut it. A single strategy will force students to think in a cookie-cutter format and limit their potential to wield writing as a tool that would benefit them. To become better writers, students must be introduced to new writing situations and adapt to using new writing strategies. Doing so will strengthen students’ ability to think critically and write effectively for each scenario.

Let me demonstrate with a common example. How many times have you heard a wedding speech start with some variation of “Merriam Webster defines love as…” along with some cheesy phrase at the end of it. A common strategy, isn’t it? Almost so common that a wedding wouldn’t be complete without the utterance of that phrase. Let’s say you had Great Aunt Tessie’s funeral to attend, and Cousin Dan is asking you to come up and deliver some loving words. Can you imagine if you came up and said, “Merriam Webster defines death as..” paired with some weird anecdote of Great Aunt Tessie? You can kiss that inheritance goodbye! I mean, hello, read the room. Now, think about this method for your college essays. You would apply the same opener, the same format, and the same tone for every piece, regardless of the prompt or the class it called for. Every essay would become redundant, and the effectiveness of the strategy is gone.

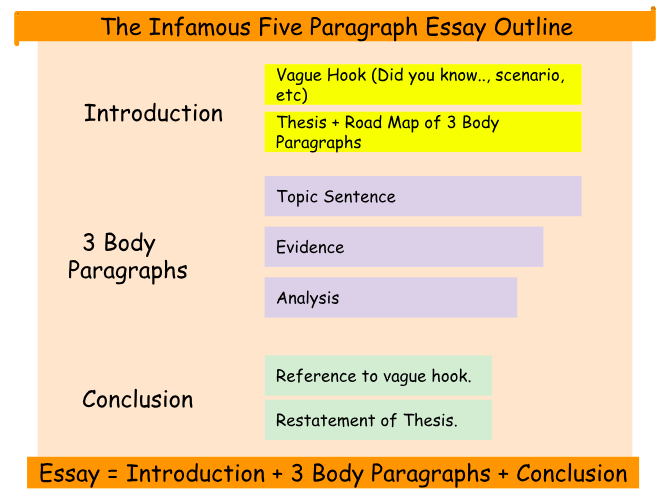

This all, however, is theoretical. To really find out if using the same strategy is feasible and productive for learning, let’s examine the Five-Paragraph Essay (FPE). The five-paragraph essay taught in elementary and high schools, is a distinctly marked essay writing technique with an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion that restates the thesis. Bruce Bowles, theorist and researcher on composition at Texas A&M, describes this method as a product of “assessment washback” (221). With assessment washback, instead of teaching what a normal curriculum should look like, teachers resort to teaching students how to take tests and more importantly, score well on them. The five-paragraph essay is a hallmark of standardized testing, as it makes grading easy for testing companies and provides an assurance that, if done properly, a student would receive a high score. Its popularity in curriculums has established the format to be the high school student’s go-to essay strategy. The virus of the five-paragraph essay has spread outside of the test room and has crept into the homework assignments and essays. Students have begun to use this format over and over again in response to every prompt and for every class.

While marketed as a strong default approach, the five-paragraph essay actually hurts a student’s quality of writing as it doesn’t allow students to think critically about their work. As Bowles puts it in his essay, the five-paragraph theme:

Imparts a hollow, formulaic notion of writing to students that emphasizes adherence to generic features rather than focusing on the quality of content, informed research practices, effective persuasive techniques, and attention to the specific contexts in which students will compose. (221)

Students rely on hitting all the structural criteria in the five-paragraph essay and neglect to think about the rhetoric of their work, their argument, or include skillful thinking. This formula has become a crutch that’s allowed students to become blind to their work, prioritizing quantity over quality. Rose demonstrates the theory of continual learning in writing, and Bowles executes these ideas as he explains how the five-paragraph essay prevents learning and growth as a whole.

Let’s take a look at an example student, Katie, who is working on an essay for school. Because modern-day school curriculums revolve around standardized test preparation, the essays assigned to students will often look the same way as tests would: with a hallmark oversaturated topic, such as abortion, death penalty, or dress code, and a strong emphasis on the FPE. So, in this case, Katie will be writing an essay arguing the death penalty. Katie, like many other students in high school, relies on the five-paragraph essay formula to pull her through this assignment. See her diagram below.

Katie will plug her ideas into this formula and apply the “generic features” she was taught to create this perfect amalgamation of public-school blandness. She might use strategies like a basic hook such as “Did you know?” or include some vague scenario, then neglect that same hook until the last paragraph where she might mention it once or twice, as an attempt to “tie it all together.” If you look closely at the diagram, you may notice that the body paragraphs only really have room for topic sentences, evidence, and analysis. The evidence most likely comes from the same source that was provided by the teacher, so naturally, everyone in the class is using the same evidence. After that, it’s not hard to even have some of the same arguments and analyses. In fact, Katie’s argument not only sounds like the many other students in the class, but you can almost mistake them for any argument pulled from a generic online search. With a formula like this, it would be incredibly difficult to add substance or depth to your argument. Look again at the five-paragraph essay diagram. There is no room for counterarguments, personal evaluations, connections to current events, or any nuances that give your writing power. The special thing about Katie is that she has an uncle that’s been incarcerated in the U.S prison system. Her perspective on criminal justice would be critical in an argument like this, but there is no space for her thoughts in the formula. So, for fear of losing points, she didn’t bother contributing her insight. “It doesn’t matter, anyway. This essay doesn’t include me,” Katie thinks. Instead, she focuses on hitting all the structural points: introduction, three body paragraphs, and conclusion. She turns the paper in. She gets an A in exchange for her ideas to remain unheard.

With the five-paragraph essay, writing has become gamified. Students like Katie use the formula to play “how many points can I get if I write an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion?” Internal questions spur such as, “How many more points will I get if I use big words I don’t really understand? What if I use a hook? What if I restate my thesis in the conclusion?” drive her thinking. You are no longer earning points for your work – you’re winning them for your obedience. Andrea Lunsford, editor, and English professor at Stanford University, discusses how writing is performative in many situations. “Writers interact with, address, invoke, become and create audiences,” and writing is used to declare events, create change, and to inspire knowledge (21). With this, the five-paragraph essay clearly demonstrates how students are performing for a grade. The formula has transformed the study of writing from a practice of a critical tool into a thoughtless vehicle for an A.

The effects of the five-paragraph essay damage not only the quality of the work but limits the scope of one’s learning. In fact, the five-paragraph essay has encouraged students to stop learning altogether. Students have stopped differentiating new writing situations they are put in, and in turn, have stopped using new strategies. Rose illustrates the same concept when she states that “writers must struggle to write in new contexts and genres, a matter of transferring what they know but also learning new things about what works in the present situation” (60). It is critical for a student to struggle in a new writing situation to learn and benefit from using new strategies. Every writing situation has its nuances and quirks. So, a student’s strategy may apply well to one situation, but cannot be recycled for another. For example, a student that applies the five-paragraph essay for an English class about Shakespeare would be making a poor decision to apply the same format to their scientific paper for Biology. The introduction, three body paragraphs, and conclusion will not be appropriate for your lab report, and more than that, would lose your credibility. Therefore, when students use the same format for each essay and constantly recycle, they do themselves a disservice. They don’t practice new writing. It is merely a rehearsal of old strategies. This expression of bland uniformity is where the beauty of writing gets lost.

Students need to know that this “beauty of writing” is that learning is never ending. Rose eloquently states, “one of the first lessons writers learn, one that may be either frustrating or inspiring, is that they will never have learned all that can be known about writing and will never be able to demonstrate all they do know about writing” (59). While writers will not be able to know everything about writing, the best they can do is to understand the situation they’re writing for and learn more about it. The most skillful writers are the ones who are the most willing to learn. Realizing that writing is a lifelong learning experience has given me room to breathe and opportunities to grow. It is okay to be imperfect in my writing because imperfection is a requirement; imperfection is what leads us to learn. Chasing perfection would simply be foolish.

As a college student that has recognized the beauty of such writing, I am heartbroken to see the effects of the five-paragraph essay on students today. It must be impossible to try to embrace a practice that’s only been regarded as a way to achieve test scores. It must be impossible to love something that feels so mechanical and formulaic. More than that, however, it must be hard to not truly be able to express your most unique ideas.

With the five-paragraph essay formula, students have internalized that schools don’t actually care about what you have to say. What they’re prioritizing is the structure of your essay and if you’ve met all the points. There is no room for creativity in a formula. What’s more tragic is that we’ve accepted this after tireless usage of the format. We have had new ideas but have been told not to chase them.

We’ve strayed from writing. Real-ass writing. Writing that someone gives a fuck about. We must unlearn traditional and non-helpful practices that have come from “assessment washback” (Bowles 221). When we are able to truly think and internalize our arguments, using all of our resources and potential, it is then that we may use writing as a tool to change minds. It is then that writing has power. Understanding the origins of these writing constraints will help students break free from them and produce more organic writing.

On a larger scope, we, as college students, must take action and change the school systems that have failed us. Bowles suggests that to eradicate the reliance on standardized testing and “assessment washback,” schools should use local school assessments and GPA for funding (224). Rose advocates for the practice of continually putting students into new writing situations to learn and grow (61). By merging Bowles’ ideals of a new format for the school system and Rose’s approach to writing, students can think more deeply about their own writing practices, reflect on them, and improve. If we don’t fix our school systems, let us mourn the death of critical thinking, free-flowing ideas, and quality and sound arguments in the essays our students write.

Works Cited

Rose, Shirley. “All Writers Have More to Learn.” Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, edited by Linda Adler-Kassner, Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State University Press, an imprint of University Press of Colorado, 2015.

Bowles, Bruce. “The Five Paragraph Theme Teaches Beyond the Test.” Bad Ideas About Writing, edited by Cheryl E. Ball and Drew M. Loewe, West Virginia University Libraries Digital Publishing Institute, 2017, 231-235.

Lunsford, Andrea. “Writing Is Performative.” Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, edited by Linda Adler-Kassner, Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State University Press, an imprint of University Press of Colorado, 2015.