by Lynn-sarah Georges

Lynn-sarah Georges is a business management major with a concentration in finance. She is Haitian-American and was raised in Medford, MA. Lynn-sarah says that this essay was important to her “because I had never felt like it was accepted or okay to write in my true voice in an academic setting. I feel passionate about ‘knowing who you are when you write’ because that feels like activism in the classroom.” As a student who speaks English, Haitian Creole, and French, it is important to her that she is “not only writing in my own voice but also being able to use academic techniques to bring attention to a student’s identity in writing.” Lynn-sarah states that “as a woman of color, this essay was not just special to me, it was me. This essay was me, and every other black and colored student in the classroom.” Lynn-sarah is the first of three children, from an immigrant and single-mother household, and she credits her family, and religious beliefs, for her passion to speak up for those around her.

Gettin’ to Know Harris

In my opinion, Joseph Harris makes the best argument for the use of intertextuality in your writing. In simple terms, intertextuality can be defined as the relationship between all texts. His entire project is based on explaining to writers why we “always write in response to the work of others” (1). In other words, every text is a response, in one way or another, to another person’s idea. Harris values intertextuality and believes that we should “move in tandem with or in response to others, as part of a game or dance or performance or conversation” (4). That is, in order to grow as writers, it is vital that everything we say is either in response to or to contribute to what somebody else has said. This is what forms the chain of writing we call: intertextuality. We can capitalize on intertextuality not by restating what they have said, because in the long run if everyone just repeated what was said before, the conversation would go nowhere. Instead, we can explain the other texts’ ideas, and then use our own voice to build on the conversation.

We can build onto the conversation by “coming to terms” with other people’s texts and using our voices to add to the conversation (Harris 14). Harris explains the idea of “coming to terms” with a text as such: to come to terms with a text you have to give the writer credit for their ideas whether or not you agree with them personally. Then, you have to re-explain what you think they were trying to say from “the perspective from which you are reading it” because “each of us comes at what we read through our own experiences and concerns, and so each of us makes a slightly different sense of the texts we encounter” (Harris 16). Harris is very intentional about how he defines “coming to terms” with the different texts we encounter. Many times, in his project he emphasizes that we are only able to do these things, such as “coming to terms” with other texts and contributing to the conversation, because we are all “slightly different” (Harris 16). In writing, Harris describes this as voice.

Burke’s Conversation Theory

I can better explain these concepts of intertextuality and voice through an illustration explained best by Kenneth Burke. Burke presents the idea that writing is like an Unending Conversation. In this case, I will refer to his theory of the Unending Conversation as the “Intellectual Conference.” It goes like this: you are invited to a conference about a very important topic. Intellectuals from all over the world are selected, and you are one of them. As Burke suggests, you walk into the room, but first, you sit and listen to understand what the topic at hand is. Then you begin to listen to understand what other people are saying. After understanding, you prepare to speak (Burke). If we look at this through the lens of Harris, we know that when you do speak, you will add something to the conversation, by saying something a bit different.

But let’s say in this case, before speaking, it has become very clear that everyone has been repeating the same thing. The tall white man in the suit makes a statement. Then the dark lady adorned in jewels and brightly colored fabric repeats the same exact statement. Then the young teenage girl asks to speak and says the same exact thing. This cycle goes on for hours without variation. My question to you is: would you stay in this room? Would you stay and participate in a conversation where everyone seems to be repeating the same thing? This is not an “Intellectual Conference.” I don’t know ‘bout you, but my momma always told me, “your time is precious, don’t waste it”. I would leave, and I bet you would too. This is because, as Harris says, we are all different and have (or should have) something different to add to the conversation while acknowledging that our thoughts came to be because of what others have said.

Harris, that one guy that just be enlightening errybody. I done read his paper, and I know now that your voice is that one thing you got in academic writing that ain’t no other soul got. What you go to say, that ole’ dude ain’t already saying? When you write with your own voice, you get to be you. You ain’t gotta lie ‘bout what you done been through in life because you can use that in your writing. The way you write, and what you be writing should “say a good deal about who you are as a writer, about your own interests and values” (Harris 16). If we go back to the example of the “Intellectual Conference,” we can see that in that room there were a variety of people. People of different races, gender, age, etc. All kinds of people engaging in a conversation. Because of this alone, all of those people have at least one thing to say that is different from what someone else said. What they say and the way they say it according to their experience and their “interests and values” is their voice. Other people value what they say because everyone trusts, based on how they contribute to the conversation, that they are educated on the topic at hand. In writing, this would be defined as an authoritative academic voice. This is slightly different from voice. It’s like voice, but with sprinkles on top. Authoritative academic voice is what qualifies you to speak on a particular topic. It is the one thing that lets everyone in the room know that you are speaking and persuades them to listen.

Code-Switching and Voice are Homies Forreal

I’m pressing you ’bout Harris’s ideas on intertextuality and voice so badly because I want you to see and understand why I believe limiting code-switching in educational institutions is a problem in writing. Aneika Robinson is a Jamaican American student at the University of Massachusetts Boston. Robinson argues that teaching institutions should recognize that code-switching is language blending and not language conversion. Black English is not another language, but instead, another form of English. Therefore, the way we are taught in school should reflect African American history and culture so that Black English is not viewed as less than Standard English but rather a mix of “Standard English and black vernacular” (Robinson). In educational institutions, students should not be looked down upon for code-switching. We ain’t none less than errybody else ‘cause we got enough skill to blend history and language. Black English is not an exception to good writing because it takes skill for a student to “understand, listen, and write in multiple dialects” at the same time (Robinson).

Looking at this through Harris’s lens again, we know that in order for a student to properly understand and interact with other texts in writing they have to be able to come to terms with the text and be able to respond to it in their own way that is unique to their voice, therefore setting up the platform for they own academic authority. Robinson argues that educational institutions are not made in a way that embraces the voice of African American students. This be a problem because it’s a contradiction within itself. How us black folks ‘posed to write in our own voice like Harris suggests we do, but then not use our own voice when we write because it’s improper like the white people at school done taught us? Make it make sense!

We see proof of this through a phenomenon called “code-switching.” Robinson uses Vershawn Ashanti Young to define code-switching as “accommodating two language varieties in one speech act, which in simpler terms is the practice of language blending” (Robinson). In other words, code-switching is not the act of speaking a different language, but instead, the product of history and culture blending into a language ultimately becoming part of the identity of the person using the blending. Educational institutions on the other hand have purposely trained students who use code-switching to abandon this part of their culture and history, also this part of “who they are” when in school. They classify it as “improper” or unprofessional. This poses a problem of voice for students of color. For instance, as a Haitian American student, I know well enough to speak “Proper English” at school, and then “Black English” with my friends or at home. This is so because through educational training I have been taught that, if I want to get a good grade, I need to conform to Standard English. On the surface, this seems to have no effect. Just changing how I speak, right? NO! When you look a bit further, the act of filtering culture and history in the way that writing is taught in educational institutions is causing a fundamental problem of identity in Black American students due to the loss of voice. Who am I when I write? Am I the black Haitian girl? Or am I the not-so-American American? The answer is: I don’t get to choose, ‘cause all my life schools done told me, in they own fancy way of course, black kids like you are only seen, not heard in writing. So instead, they taught me that when I write, I gotta be in the voice of a middle-aged white man, with racks in the bank, multiple estates, a successful business, and maybe some kids.

Harris also says that we need to be able to respond to another text and “come to terms” with it. Specifically, he says when doing this, the readers should be able to see clearly, “who you are as a writer” (16). How can that happen if students aren’t even able to “come to terms” with themselves? Robinson explains that educational institutions need to “teach how language functions within and from various cultural perspectives” by not removing culture, history, and background from the learning of the English language, specifically in writing (Robinson). Even now we can see how detrimental the lack of inclusiveness is to the way students write. This shows up prominently when looking at essays written by students in school. Tyler Tran is a student at UMass Boston who is passionate about uncovering why students do not use their own voice in writing. He claims that intertextuality, the teaching of detachment in school writing, and the teaching of Standard English as proper English all lead to students self-censoring themselves and results in a loss of voice over time. Tran references the words of high school teacher Rebecca Gemmell, who says that oftentimes her students “all sounded the same” (Tran). He blames this on a few factors. Tran claims that “intertextuality is a reason why it may be difficult for students to write using their own voice.” Tran builds on the idea that students have detached themselves from their writing. I agree with him on that point. Students definitely do not write in their own voice, but I disagree with the fact that he says that the “self-censorship” is because of the pressure of intertextuality. I believe it is students doing things the way they have been trained to do so. Teachers have unintentionally, or intentionally, muted students’ voices and taught them to impersonate others through the way writing is being taught in lower levels of education. Educational institutions are limiting the texts provided to one voice: the Standard English voice. Then on top of that, they proceed to teach students that Standard English is the “dominant language” and that their race, culture, history, and overall identity should be ignored. When you take all of these things into consideration, you can see how it would be almost impossible for Black American students to properly take part in the conversation created through intertextually, according to Harris’s terms.

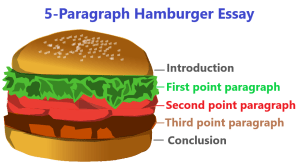

A simpler example of this is standardized testing and the five-paragraph essay format. Students are not only told to write a certain way (Standard English). On top of that they are told how to write it. For students who code-switch, there is another layer of limits because they are also told whose voice to narrate it in. For the white student, this is less repressive to their identity than it is to the student who code-switches. This is because the white student gets to still speak the form of English their history and culture resonates with. On the other hand, the students who code-switch have to learn, understand, and then take on the form of the white students’ English in order to be deemed intelligent enough to participate. If not? Well then, in that case, they would fail the standardized test. Why is it fair for the students who code-switch to have to learn and understand a new language code, but the same is not asked of the white students? In short, if students don’t know who they are, they cannot write with an authoritative academic voice because their voice has been forbidden in educational institutions.

To finish off, let’s go back to the illustration of my Intellectual Conference to explain what this feels like for students who code-switch. For students who code-switch, it feels as though we were invited to that conference but only to be told to put bags over our faces and attach mirrors to our bodies to echo only what has already been said. Unlike everyone else, we are given rules on how to speak. Immediately, and before walking into the room, we already understand that if we want to be in that room of intellectuals, we cannot be ourselves. We have to reflect someone else’s ideas, history, culture, voice, and ultimately: identity. But aight, I ain’t gon say too much, just that, the way we taught to speak and write in them white folks school goes beyond a five-paragraph essay, it goes beyond “English class.” It seeps into our identity. How I speak is who I am. And my identity has everything to do with how I write. I shouldn’t be forced to change who I am, whether or not it looks like Standard English because my voice, my culture, and my history have a place in the conversation. Before I let you go, imma ask you one mo’ question: whose voice do you write in? Or in Harris’ words, can readers get a jist of “who you are as a writer” from the voice you write in (16)? Or are you still wearing your paper bag?

Works Cited

Bowles, Bruce. “The Five-Paragraph Theme Teaches ‘Beyond the Test’.” Bad Ideas About Writing, edited by Cheryl E. Ball and Drew M. Loewe, West Virginia University Libraries Digital Publishing Institute, 2017, pp. 220-225.

Burke, Kenneth. The Philosophy of Literary Form: Studies in Symbolic Action. 1st ed., University of California Press, 1973. JSTOR.

Harris, Joseph. Rewriting: How to Do Things with Texts, Second Edition. University Press of Colorado, 2017. JSTOR.

Robinson, Aneika. “The Marginalization of African Americans in Educational Institutions through Race and Language.” Undercurrents: A Journal of Undergraduate Student Composition, 2020.

Tran, Tyler. “It’s Your Voice, Why Not Use It?” Undercurrents: A Journal of Undergraduate Student Composition, 2021.