Sometimes a misquotation is so entrenched that it becomes strangely acceptable to paraphrase the misquote..

In an editorial about economic revival of New South Wales, the writer did this, using a misquote of a statement made in 1953 by “Engine Charlie” Wilson, longtime the head of General Motors. The editorial began this way [emphasis added]:

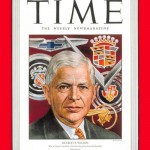

One of the most famous misquotations in history is often attributed to Charles Erwin Wilson, a former president of General Motors who became the U.S. Secretary of Defence in 1953.

At the time of his appointment Wilson was supposed to have said: “What’s good for General Motors is good for the country.” His actual words were significantly different, but the misquote lives on.

To paraphrase Wilson, what’s good for NSW is very definitely good for Australia….blah, blah, blah.

WHAT?

The writer established that Wilson’s statement is often misquoted. Great.

Furthermore, they write, Wilson’s “actual words” were “significantly different.” Great.

Also, they add, “the misquote lives on.” So far, so good.

Where are they going with this? Will the writer correct the record and give Wilson’s “actual words”? The writer heads in another direction. They ease it into first gear and step on the gas, plunging ahead. He or she takes the misquote, acknowledges it as a misquote and then uses it as the takeoff point for the editorial–following the same rut in the road that many.

Yes, indeed, it is a shame that “the misquote lives on.” The writer, acknowledging that fact, then adds to the longevity. The editorialist simply could not resist using the common “what’s good for X is good for Y” formula.

The trouble is that Wilson was more suble and made a more challenging point. The misquote is based on something he said during his confirmation hearings before the Senate Armed Services Committee, after he had been nominated by President Eisenhower to be Secretary of Defense in January 1953. Wilson was president of General Motors at the time. At one point in the hearings, Sen. Robert Hendrickson (R-NJ) asked him if he could make a decision as secretary of defense that would be detrimental to the interests of General Motors. He said he could, adding [emphasis added]:

“for years I thought what was good for our country was good for General Motors, and vice versa. The difference did not exist. Our company is too big. It goes with the welfare of the country.”

Unfortunately, it apparently took too long for the entire quote to come out. The hearing (on 15 January 1953) was closed. According to this wonderful retrospective, the Detroit Free Press, scrambling for information, reported Wilson’s comment (second-hand, and a few days after the hearing) in this way [emphasis added]:

“His answer, as quoted by one senator, was ‘Certainly. What’s good for General Motors is good for the country’.”

That’s all that many people needed to hear, and that early twisted, shorthanded, hearsay version became a staple anti-business commentary. It is, after all, a wonderful embodiment of a patronizing attitude of a self-centered wealthy businessman and corporate leader.

Too bad it misrepresented the statement of “Engine Charlie.” And jump-started a hard-to-kill misquotation.

Crikey! The original quotation could have served the editorialist just as well as the misquotation. I wonder if they would consider the vice versa: “what’s good for Australia is good for New South Wales.”