By: Monica Haberny

In the summer of 2016, volunteers petitioned throughout the state of Massachusetts to put Question 3 on the ballot. The question involved increasing the amount of space farm animals were given in Massachusetts, affected issues of food safety, and passed in a landslide that November.

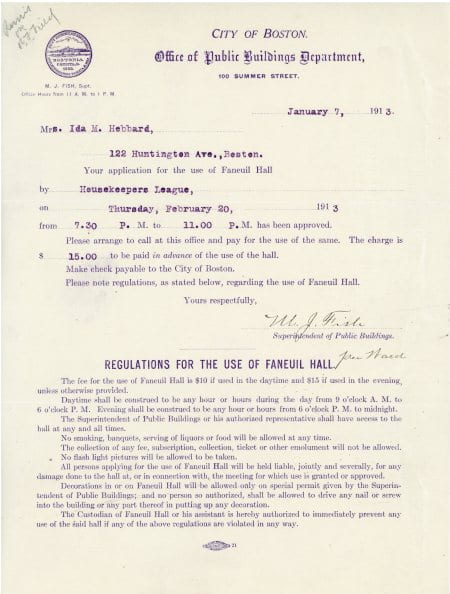

At the time, I was completing an MA in History and began working as an intern at the Boston City Archives. I used documents I found at the archive to write about women and African Americans who influenced Boston history. The one that stuck out to me the most was Ida M. Hebbard. Hebbard presided over the Housekeepers League during the 1910s and protested the surging prices of basic goods. She held various meetings about public health, worried about the cost of living for struggling families, and advocated for laws which affected food safety and animal welfare. About a hundred years later, the activists petitioning for Question 3 would follow in her footsteps.

Inspired by Hebbard, I initially wanted my capstone project to tell the story of animal welfare organizations in the Boston area and thought about creating an online exhibit. So when Jan Holmquist took me on a tour of the archive at the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, I came in with my original idea in mind. However, at end my visit I had already scrapped that idea and decided to make the MSPCA Archive more accessible to researchers by creating a finding aid. Much of the archive was already processed, but a 2008 fire had set back progress. There was also no concrete list of what records the MSPCA had; researchers needed to email Holmquist first to see if what they needed was there or make an appointment and hope that it was. Although there was a lot of work to be done, I was excited to get started.

In 1867, philanthropist and activist, Emily Warren Appleton traveled to New York and met with Henry Bergh. The founder of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) offered her advice on founding a similar organization in Massachusetts. Upon returning to Boston, she located the men who would become the MSPCA’s first donors and began working on a charter. A year later, George Thorndike Angell published an editorial in response to two horses that were raced to death after traveling a distance of forty miles. Appleton immediately went to Angell’s office after seeing the article, and together they founded the MSPCA. Angell became the first president; during his term, the organization pushed for the passage of multiple anti cruelty laws, published “Our Dumb Animals,” created the first American Band of Mercy, and began the distribution of children’s classics like Black Beauty or Beautiful Joe.

Dr. Francis Rowley took Angell’s place as the MSPCA’s second president in 1910 when Angell passed away in 1909. Rowley expanded the influence of the MSPCA. He oversaw the creation of the first MSPCA shelters and Angell Memorial Hospital. The hospital would be at the forefront of new practices in veterinary medicine, like the world’s first veterinary intern training program in 1940 or the first successful feline kidney transplant in 1997. Rowley also helped build the American Fondouk Maintenance Committee in 1929, a humane organization in Fez, Morocco. This event served as the first of many instances where the MSPCA fought for animal welfare abroad.

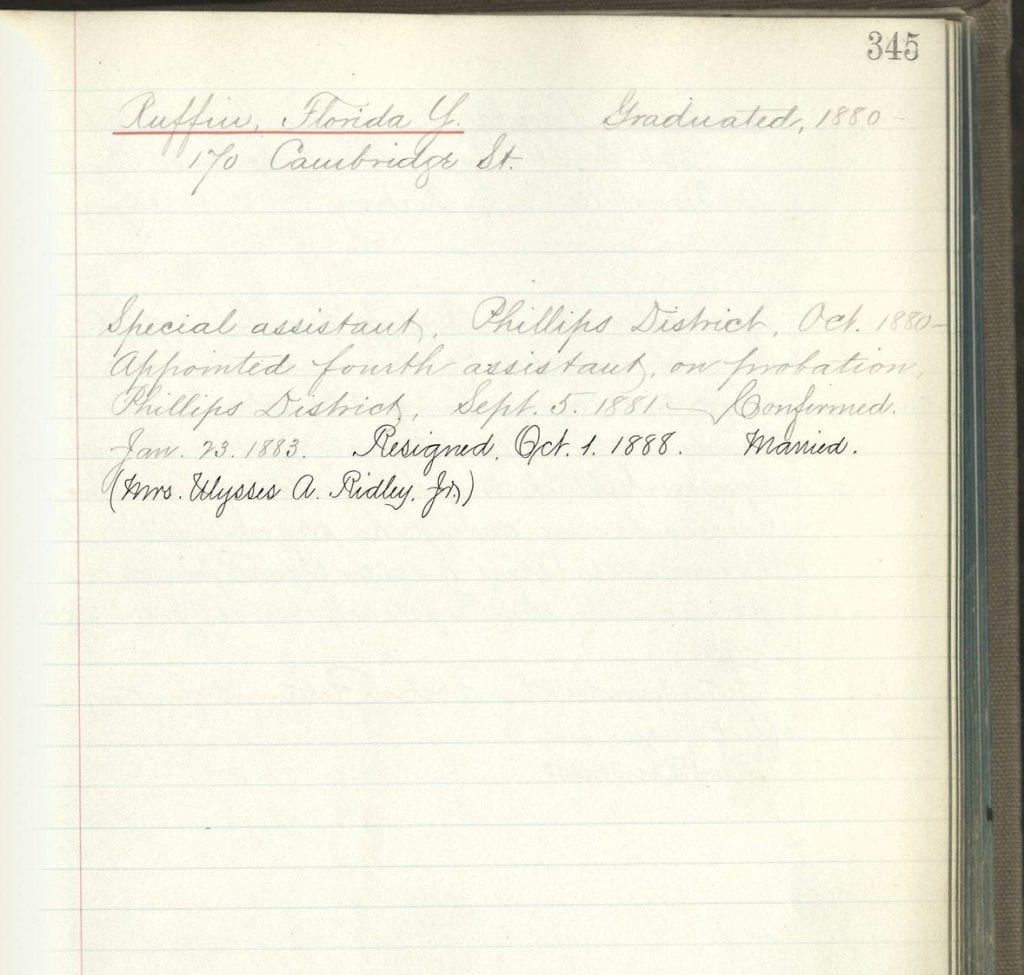

Despite the accomplishments of Appleton, Angell, and Rowley, many of their letters and documents may have been lost in the 2008 fire. I began my work at the MSPCA going through Angell’s correspondence and early records. A portion of the letters between Angell and his mother were burnt or missing. However, the correspondence that did survive gives insight into Angell’s upbringing and character. Even rarer, though, are records from Appleton and Rowley in their hand. The MSPCA Archives has a copy of Appleton’s will and she’s mentioned in various record books, but not much else. Only a few of Rowley’s letters survived the fire. It’s impossible to know just how much was lost, because of a lack of a finding aid before the fire.

After surveying early records, I began processing documents that were still disorganized from the fire. In about five boxes, I found records from the American Fondouk, correspondence from MSPCA employees, and many media clippings. The MSPCA Archive had amassed a large collection of newspaper and magazine clippings that mentioned the organization, the hospital, its many shelters, and other organizations that they were connected to. The clippings ranged from the early 1900s to the 2000s, the majority of which were from the 1970s up through 2005. While it would have been great to scan the clippings, as newsprint doesn’t preserve well, I had no means of doing that. So I spent time putting all of these clippings in chronological order and into boxes by decade. I learned a lot about animal welfare history in the 20th century from these clippings. For example, the MSPCA worked with the Franklin Park Zoo in the late 1970s and early 1980s to upgrade the zoo and improve conditions. I would sometimes separate articles not just chronologically, but by event as well. I did so with articles about the zoo in the 1970s.

When going through the records of the MSPCA and creating the finding aid, I not only learned a lot about animal welfare history, but I also realized how a collection can take a toll on the archivist processing it. Sometimes the subjects presented can hit close to home, and this was especially true with how big animal welfare had become in my life. The records at the MSPCA mentioned various issues like donkey basketball, greyhound racing, and instances of animal rescue during natural disasters. In addition to records of successful legislation and uplifting stories, there were also images of animal cruelty. Around the 1950s, employees at the MSPCA wrote to various companies which sold humane stunners and pistols asking for brochures. I also had to process articles on different methods of euthanasia. This aspect of the collection, while important to preserve, was particularly hard for me to look at.

Coming into this project, I was extremely attached to the subject matter. I wanted to list every single record I came across. My finding aid would include everything from documents and photographs to audiovisual material and medals. In the middle of my project, my advisor, Dr. Marilyn Morgan, confronted me with reality. She told me that processing and recording everything at the MSPCA was impossible if I wanted to graduate in December. She also made me realize that my time at the archive wouldn’t have to end when I submitted my finding aid. With her guidance, I focused on what I could actually get done within the time I had. I began selectively processing and recording things. I listed all of the boxes on the finding aid, but not all of the folders inside of them. For example, I didn’t list all of the folders for the many boxes of publications. I knew that any researcher looking for a newsletter or magazine could find what they needed in the labeled boxes and all the folders within them were in alphabetical order. My finding aid ended up focusing entirely on the documents and a small portion of the books. The photographs, audiovisual items, oversized materials, and ephemera needed to be left for another time.

That time came less than two months after I submitted my finding aid and graduated. I became a consultant in February. I work a few hours a week helping Jan Holmquist keep up with the archive. This includes processing new materials, adding to the finding aid, researching the history of the MSPCA, and finally being able to go through all the materials I missed last time around. The project I’m most excited about is going to various archives and learning more about Emily Warren Appleton.

Animal welfare activism has grown in the last decade, and while Massachusetts has been on the forefront of this issue since 1641, the history isn’t too readily available yet. I know that my work will change that. The past will become more accessible to researchers and activists will be able to learn about how far animal welfare has come in almost four hundred years.