By: Laura Kintz

During the Fall 2015 semester, I had the opportunity to complete my required archives internship at the City of Boston Archives in West Roxbury. This was a wonderful learning experience that allowed me work on processing an important archival collection: the records of the Boston 200 Corporation, which planned and managed the city’s United States Bicentennial celebrations in 1975 and 1976.

Before beginning this internship, my processing experience was limited to the Spring 2015 Archival Methods and Practices course, in which we processed the collection of the Jamaica Plain Historical Society. That project was very challenging because I worked mainly with photographs for which there was no significant original order; they were just unorganized, loose photos with very little, if any, identifying information. In addition, the JPHS did not have an established archival collections policy, so much of the work we did was from scratch. Processing the Boston 200 collection gave me the chance to work with institutional records that are probably more typical of the type of materials that I would work with in future processing projects at an established archive.

The Boston 200 collection specifically consists of the records of the Boston 200 Corporation, which planned and managed Boston’s United States Bicentennial celebration. The celebratory events took place mainly in 1975 and 1976, but the records that I processed date as far back at the late 1960s through the late 1970s. The corporation itself was in operation from 1972 until 1976. In its pre-processed state, the collection consisted of boxes of file folders most likely from filing cabinets or office drawers, with occasional miscellaneous materials in manila envelopes or just loose inside the boxes. The collection is divided into series based on the specific program areas of Boston 200. Of approximately 200 total boxes in the collection, I processed 20. I was able to condense the original 20 boxes into a finished product of 14 boxes. This included part of the Visitor Services series and all of the Neighborhoods series and the Environmental Improvements series.

My job was, in short, to make order out of disorder. The biggest part of this task was refoldering, since the original folders were not in very good condition nor were they acid-free, and acid-free folders are the standard for archival document storage. The folders already had labels, and in most cases I could just keep the same labels as my new folder titles. There were some exceptions to this rule; I occasionally encountered folder titles that did not accurately reflect their folders’ contents, and in those cases, I created new ones. The main reason for doing that is so that a researcher looking at the list of folders in the collection can determine which folders will be helpful; an inaccurate folder title would be misleading and waste the researcher’s time. To indicate that a folder title was of my own creation, and not the original title, I put it in brackets. In addition to the title, I also added a date range to the folder label.

Just as important as processing a collection is making it accessible. Towards that end, after completing the processing of each box, I cataloged it using the ArchivesSpace platform so that the collection will be searchable on the City of Boston Archives website. ArchivesSpace allows for the hierarchical entry of information that can be migrated into a finding aid. I entered folder information at the “file” level underneath the appropriate series within the collection. The most important information that ArchivesSpace captures is the folder title and dates, but I also added information related to the document type (always “paper,” except in the case of photographs) and the materials’ physical location in the storage room. This example shows my entry for a folder titled “Neighborhood History Series booklets” and dated 1975-1976, which I entered as a file unit under the Neighborhoods series.

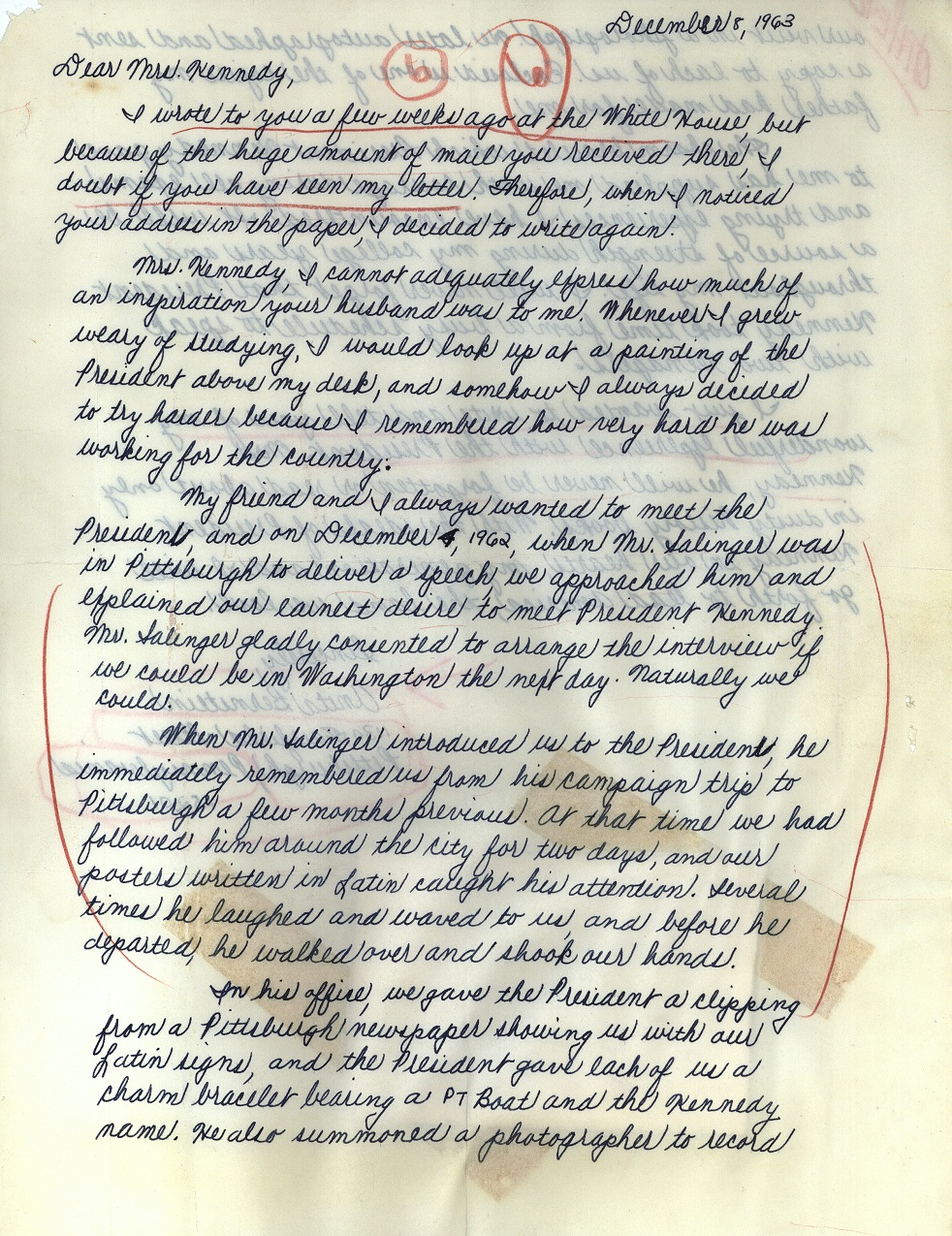

The majority of the materials that I processed and cataloged were textual, but I did encounter some photographs as well. There were two general types of photographs: those that documented Boston 200 activities and those that did not. Photos in the latter category were related to things like advertising or proposals from potential vendors. This distinction is important because I handled these two types of photos in different ways. For the unrelated photos, all I did was insert them into mylar photo sleeves and return them to their original folders. When I found photos related to Boston 200 activities, on the other hand, I separated them out to add them to their own Boston 200 Photographs series. I gave each of these photos their own identifying number (or digital identifier), inserted them into mylar photo sleeves, scanned them, uploaded them to the city archives’ Flickr page, added identifying and copyright information, and entered them into ArchiveSpace (at the item level, not just the folder level). I also put the photos into their own folders with titles that corresponded to the folder that they originally came from. Most photographs that I encountered did not have any identifying information, but in the interest of time, I did not do much research to identify people or places were not recognizable. That is where the Flickr platform can come in handy; the site allows registered users to view and comment on photos, and users have occasionally been able to identify people and places in city archives’ photos that staff could not identify. Below is a screenshot of the Flickr page, as well as three examples of photos that I scanned and cataloged.

Credit: Boston 200 records, Collection # 0279.001, Photographs, Boston City Archives, Boston

Credit: Boston 200 records, Collection # 0279.001, Photographs, Boston City Archives, Boston

Credit: Boston 200 records, Collection # 0279.001, Photographs, Boston City Archives, Boston

While the overall experience of processing a collection was the highlight of my internship experience, I also gained insight into the wide variety of research topics that just one archival collection can represent, beyond those that might seem obvious. My initial excitement in being assigned this collection was that in Monica Pelayo’s Fall 2014 Public History Colloquium, we read a book called The Spirit of 1976 that discussed United States Bicentennial celebrations from a critical public history perspective. I was interested to see how this collection could fit into public history discussions of national celebrations. It certainly would be a valuable resource for research on that topic, but its potential is so much greater. Materials in the collection document the logistics of planning such a massive celebration, which could be used by someone studying, for example, the failure of Boston’s 2020 Olympics bid. The collection also documents the vast number of improvements made to the city’s tourism infrastructure, which could be used by someone studying the history of tourism in Boston. It includes materials related to significant historic preservation projects, which could be used by someone studying the history of the Freedom Trail or Black Heritage Trail and improvements made to the city’s historic sites. It also documents a turbulent time in the city’s history, and its records provide insight into urban renewal and race relations. The research possibilities really are endless.

The Boston 200 collection is a valuable asset to the City of Boston Archives. I am so glad that I had the opportunity to hone my processing skills with this collection and to further my understanding of the wide variety of uses for archival collections. I know that I will take what I have learned with me as I continue my archival career.