By: Lauren Prescott

This semester I completed a digital archives internship at Boston City Archives with archivist Marta Crilly. Established in 1988, in an old school building in Hyde Park, the archives (now located in spacious location in West Roxbury), holds documentation of the history of Boston from the 17th century to present. Some notable collections in the archive include documentation of Boston’s role in the Civil War, immigration records, city council records, and Boston Public Schools (BPS) desegregation records. My interest in digital archives, as well as my experience in History 630, the digital archives class working with Boston Public Schools’ desegregation records, made this internship a perfect fit for me.

Desegregation

In 1961, the NAACP met with the Boston School Committee in an attempt to get the committee to acknowledge the racial imbalance of Boston Public Schools. The School Committee refused to acknowledge the presence of segregation for over a decade. In the 1971-1972 school year, enrollment in the public schools totaled 61 percent white, 32 percent black, and other minorities comprised the remaining 7 percent. However, 84 percent of the white students attended schools that were more than 80 percent white, and 62 percent of the black pupils attended schools that were more than 70 percent black. Also, during this time, at least 80 percent of Boston’s schools were segregated.[1]

Eventually, the NAACP filed a lawsuit in Federal district court in 1972, known as Morgan vs. Hennigan. The case came before Judge Wendell Arthur Garrity Jr., who made his decision on June 21, 1974. He found that “racial segregation permeates schools in all areas of the city, all grade levels, and all types of schools.”[2] The court ordered that the school committee immediately implement a desegregation plan for its schools. Garrity’s decision met with a myriad of responses from hostility and protest to submission and acceptance. Parents, teachers, politicians, and even students voiced their opinion in various ways; many sent heartfelt letters to Judge Garrity and Mayor Kevin White.*

Digital Preservation

In the digital age, archivists face challenges of acquiring and preserving electronically generated records. In addition to this, archives are constantly under pressure to make their collections more accessible, through online finding aids or digitizing collections.[3] Some repositories use Institutional Repositories (IRs) for “collecting, preserving, and disseminating the intellectual output of an institution” in digital form.[4] Boston City Archives has recently begun using Preservica to keep their digital files safe and share content with the public. Preservica does not necessarily constitute an institutional repository; but, as digital preservation software, it keeps digital files safe and accessible for institutions. Preservica contains Open Archival Information System (OAIS)-compliant workflows for “ingest, data management, storage, access, administration and preservation…”[5] In addition, Preservica allows institutions to share this digitized content with the public.

Desegregation Records

For my internship, I began the process of digitizing the Boston City Archive’s desegregation records. Because the archive contains a plethora of desegregation records spread through numerous collections, I was not able to digitize everything. This semester I worked with the School Committee Secretary Files, the Mayor John F. Collins Records and the Kevin White Papers. Not every single document can be digitized, so I was responsible for choosing records that are important to understanding the desegregation of Boston public schools. In some cases, I digitized only a few documents in one box, and in others I was digitizing entire folders.

An important part of the internship involved writing metadata. Metadata is “data about data” and provides descriptive language about a record, “such as proper names, dates, places, type, technical information, and rights.”[6] Metadata constitutes a critically important piece of digitization; without it, digital objects would prove inaccessible and futile over time. If archives presented digitized images without identifiable information, researchers could not, with certainty, understand the context surrounding the document’s content!

I wrote metadata for each document and included information such as title, unique identifier, date created, creator, city, neighborhood, description, collection name and number, box and folder location, type, language, access condition and Library of Congress subject headings (LCSH). Inputting the metadata was easier than expected, thanks to last spring’s Digital Archives class.

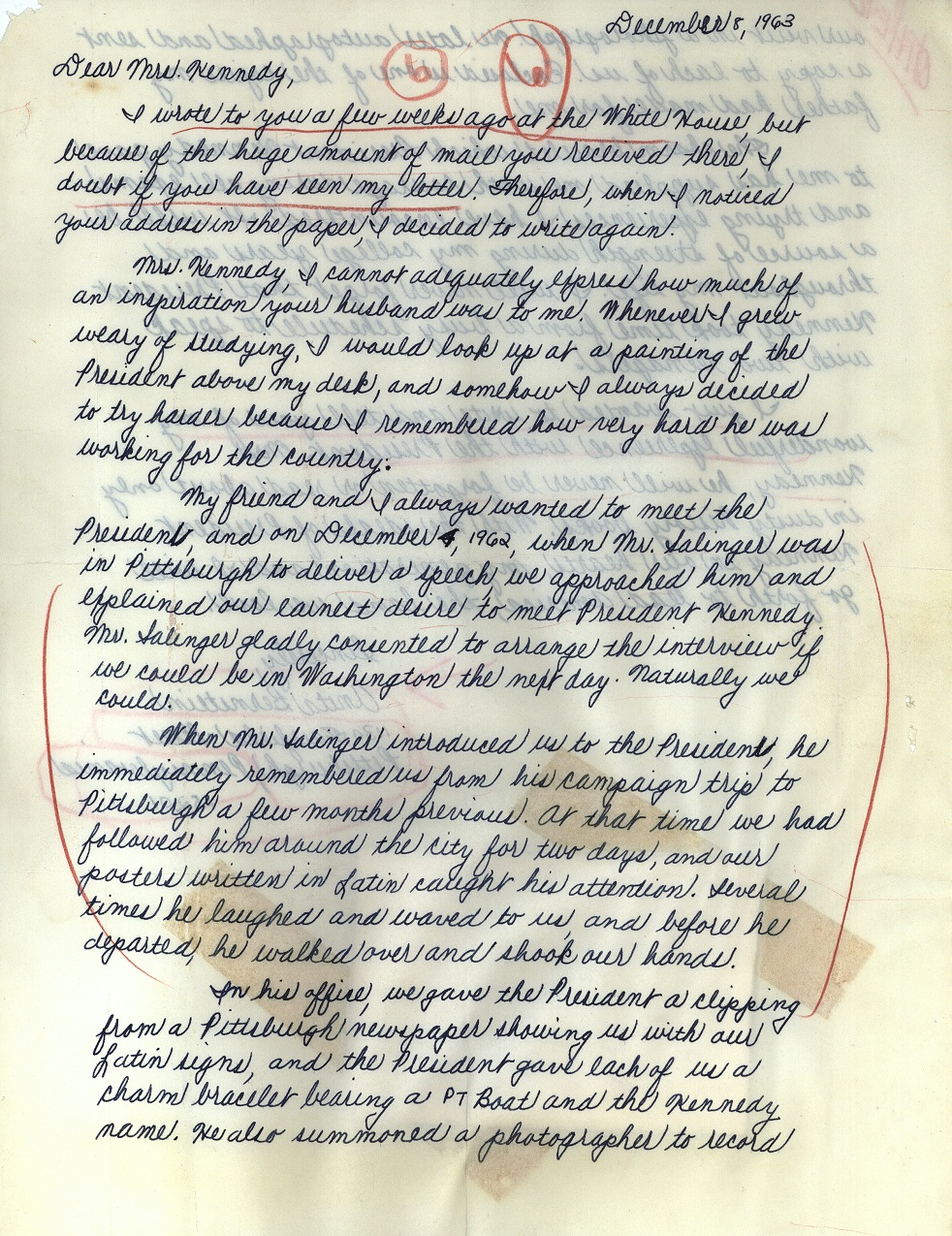

Redaction of sensitive or private information constituted another major component of the internship. I primarily redacted letters written to Mayor John F. Collins and Mayor Kevin H. White regarding desegregation of Boston Public Schools. John F. Collins served as Boston’s mayor from 1960 until 1968. While he played no official role in the desegregation of Boston Public Schools or the subsequent busing of students in the early 1970s, Mayor Collins still dealt with the problem of racial imbalance during his term. Since many of the letters expressed hostile and, in some cases, racist views, the archivist decided to redact the names and contact information of the authors. Documents written by politicians, federal and local government employees and other public figures did not require redacting.

The majority of the documents I digitized came from the Kevin H. White Papers. Kevin White served as the mayor of Boston from 1968 through 1984; this period spanned the desegregation of public schools. Documents digitized from this collection included police logs sent the mayor’s office, departmental communications, statements from the mayor and a plethora of letters, both against and in support of the mayor.

I worked with the Kevin H. White papers last semester when I created an online exhibit for class, so I was familiar with the collection; but, I still felt surprised by some of the letters I read this semester. Many of the letters Mayor White received in the 1970s were hostile and racist. Mayor White did not just receive letters from angry Boston parents, he also received letters from people in the South who had already experienced desegregation in the 1950s and 1960s, as well as several letters from other countries.

Letters written by children were my favorite documents.

Students of all ages had opinions of their own and even offered suggestions to Mayor White. Click here to learn more about students’ responses to desegregation and read a sampling of letters written by students at the time. Letters poured in to Mayor White’s office from students in Boston and all over the country. Most students were against busing, but mainly because they were afraid of potential violence. I digitized some letters from the advanced fourth and fifth grade classes at the Maurice J. Tobin School in Roxbury. The students were worried that the administration would remove advanced classes during Phase II of desegregation and wrote to Mayor White to express their concerns.

My internship at Boston City Archives was one of the best I have had throughout my academic career. Working directly with professionals in the field on an important project is gratifying. The purpose of the project was two-fold: digitally preserve documents relating to an important time in Boston’s history, and to share these desegregation documents with a wider audience. Not everyone can go to an archive and spend time doing research. The project to digitize Boston City Archive’s desegregation records is not over. I have digitized only a portion of the records and others will continue where I left off.

_________________________________________________________________

*For more information about the letters sent to Mayor Kevin White, see the finding aid to: the Mayor Kevin H. White records, 1929-1999 (Bulk, 1968-1983) at Boston City Archives; to learn more about the the letters sent to Judge Garrity, see the finding aid for the Papers on the Boston Schools Desegregation Case 1972-1997 at UMass Boston’s University Archives and Special Collections, in the Joseph P. Healey Library. This collection contains the chambers papers of Judge W. Arthur Garrity, Jr.

References

[1] School Desegregation in Boston: A Staff Report Prepared for the Hearing of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights in Boston, Massachusetts, June 1975. Washington: Commission, 1975, 20.

[2] Ibid., 71.

[3] Christina Zamon. The Lone Arranger: Succeeding in a Small Repository. Chicago: Society of American Archivists, 2012, 39.

[4] Ibid., 45

[5] “Preservica.” How Preservica Works. Accessed May 13, 2016. http://preservica.com/preservica-works/.

[6] The Lone Arranger, 47.