By: Sarah K. Black

I spent my fall 2018 semester working as a curatorial intern directly under Laurel Racine, Chief of Cultural Resources at Lowell National Historical Park (LNHP). Maintained and operated by the National Park Service and spanning a full 142-acres, the park “interprets and preserves significant historical and cultural resources from the 19th-century American Industrial Revolution.” More than just a conglomerate of former mill buildings, and a locks and canal system, the Park is a hub for education and a major player in Lowell’s evolving cultural landscape and economic revitalization.

I came to LNHP in search of experience in exhibit planning and execution. I also wanted to gain a general understanding of daily museum operations since I had never worked in a cultural institution. Knowing this, Laurel brought me in to assist two volunteers who were in the beginning stages of developing a temporary exhibit. Branding Lowell: A History of Local Design was the brainchild of Mark Van Der Hyde, a graphic designer by trade and an extremely enthusiastic and dedicated volunteer. Combining his love for both logos and Lowell, he envisioned an exhibit that centered on how the city, as well as its local businesses and organizations, have designed their own symbols and how this imagery has reflected Lowell’s collective and evolving identity since its founding.

I knew that I would walk away with more experience than I had going in, but I never expected my internship to be as valuable as it was. Not only did I grow and improve my skillset in several areas including exhibitions, collections management, and museum operations, but the opportunity also offered me a chance to prove to myself that I can step outside academia and into the public sphere of the historical discipline.

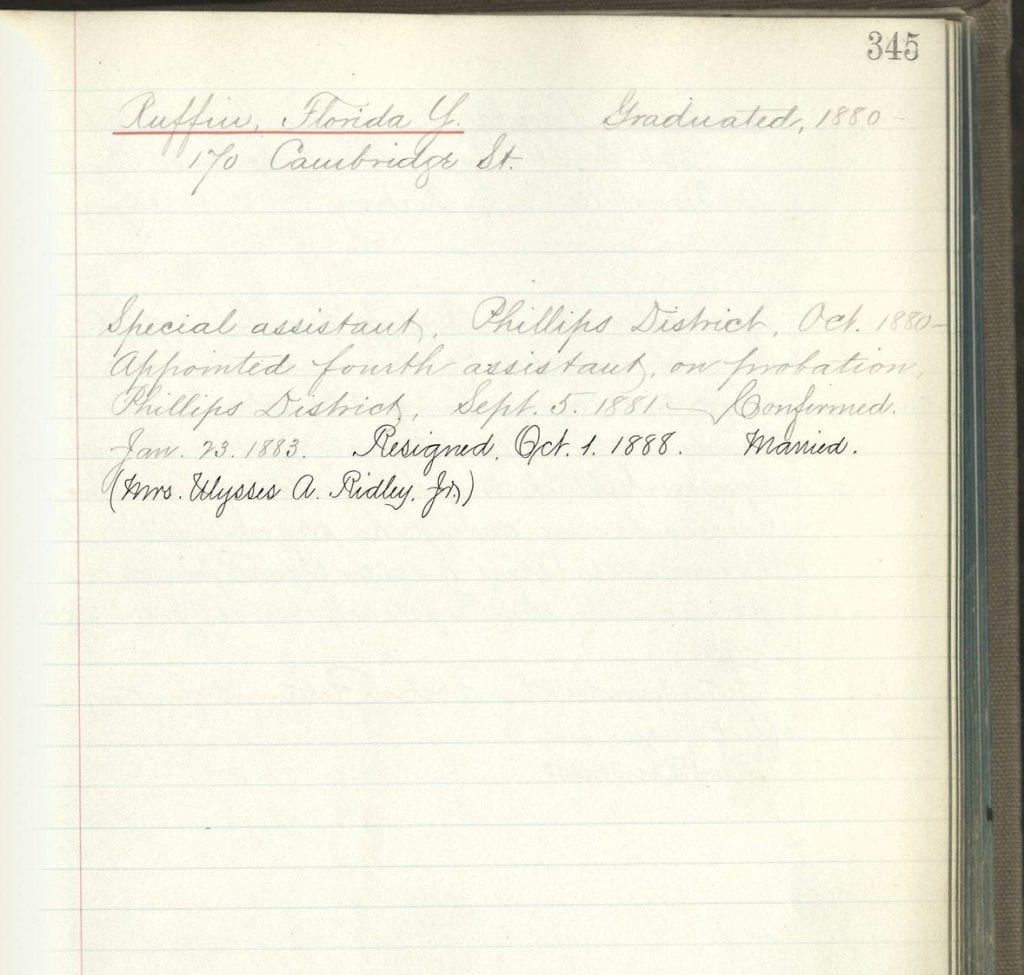

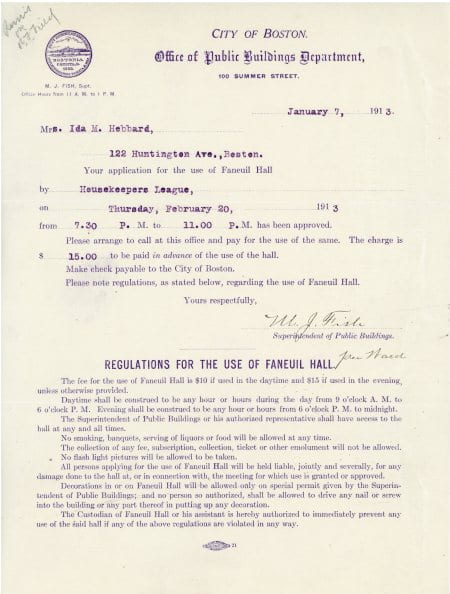

Mark had conceived of a panel exhibit with the help of Tony Sampas, Senior Digital Documentation and Records Management Specialist for UMass Lowell’s O’Leary Library— and a fellow logo enthusiast. My task—shifting the two-dimensional exhibit into a three-dimensional one—required me to research, select, and interpret artifacts to create a storyline. I spent many long hours searching through the park’s databases and experimenting with storyboards, all the while trying to find objects that both fit Mark’s narrative and illumniated stories that did not appear in the panel text. But the artifacts themselves are undeniably crucial in this history. Early sketches of the logos reveal the process of branding. Branded goods and memorabilia evidenced how these symbols were disseminated to and absorbed by consumers. Taken together, these themes demonstrate just how pervasive symbolism and branding is throughout our culture.

After just a few weeks on the job, I realized just how dynamic and unpredictable building an exhibit can be. With each team meeting, Branding Lowell grew in both content and thematic scope, and with it, so did my responsibilities. Hoping to put my training in public history theory and practice to good use, I volunteered to explore new content, draft panels, and introduce interactive components. Although these additional tasks certainly opened the door to practical experience in interpretation and exhibit planning, I found the collaborative component of the project to be the most valuable. Each member of our four-person team brought something unique to the table, be it curatorial experience, graphic design skills, or an extensive knowledge of the history of Lowell. Our exhibit team meetings were opportunities to share progress and problems; they were honest and productive sessions where we brainstormed, proposed solutions, and compromised. Collaborations, especially when they involve community members, are never a guaranteed success, so I am tremendously grateful to have worked alongside professionals who were both eager to share ideas and open to constructive criticism. In the end, our unique perspectives and expertise combined to ensure Branding Lowell is as content-rich, aesthetically pleasing, and engaging as possible.

Branding Lowell will open on March 24, 2018 and although my formal internship has concluded, I intend to see the project through to its completion. We still have a great deal to do, including case layouts and object mounts, text editing, and installation. I look forward to increasing my skillset even further.

The internship requirement for the public history program had haunted me since the evening I received my acceptance letter. I came into the program with no experience in a museum (or even a comparable institution), and feared that my lack of experience in the field would ultimately cast me as the inexperienced underdog in both academic and professional networks. But this is exactly why our time as interns is so essential. No matter how little or how much experience a student has, there are always new skills to learn, most of which have to develop outside of the classroom. I was fortunate to be mentored by a museum professional with tremendous experience in the field and a desire to create a positive and productive environment. Laurel not only took me under her wing to teach me about collections management and museum operations, but she also granted me a great deal of freedom with the exhibit content and development. At the end of the day, I will leave my internship with something even more valuable than an improved skill set: the knowledge that I left my mark on a truly dynamic and collaborative project, one that tells the story of a city’s identity in a unique and interesting way. As an aspiring public historian, I can think of no place better suited for professional and personal growth than the Lowell National Historical Park.