by Monica Haberny

In January 2017, half a million people showed up for the Women’s March in Washington DC and over four million people participated in their own marches throughout the country to raise awareness for women’s rights. During my internship at the Boston City Archives in Fall 2016, I came across many female activists who worked tirelessly for change in the past two centuries. The following three women represent just a fraction of the inspiring women whose successes and failures can motivate activists fighting for similar issues today.

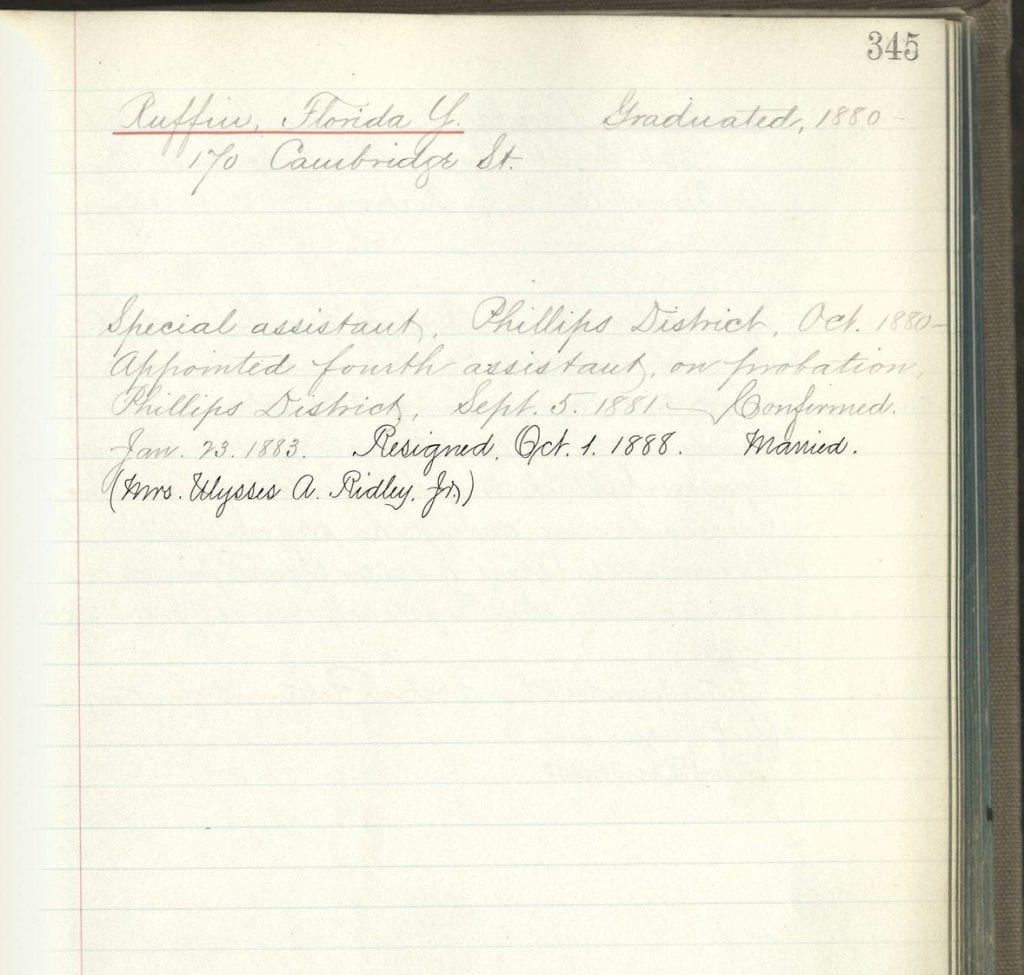

Suffragist, journalist, and anti-lynching activist, Florida Ruffin Ridley (1861-1943) became one of the first black teachers in Boston. She came from an educated background. Her father, George Lewis Ruffin, was the first African American to graduate from Harvard Law School and the first African American to be a judge in the country. Her mother, Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, a suffragist and civil rights activist, published the first newspaper for African American women. Ruffin, following in her mother’s footsteps, also worked as a pioneering journalist and activist.

Journalists provide an invaluable service, especially in a digital age where news comes from various sources and is often contested or falsely reported. Florida edited the Women’s Era, her mother’s newspaper. She wrote articles about black history and issues affecting blacks for multiple publications, including the Journal of Negro History and The Boston Globe. She, Pauline Hopkins and Dorothy West all belonged to the Saturday Evening Quill Club, an African American literary group founded in 1925. In addition to her writing career, Florida was involved in co-founding several nonprofits for African American women and was a lifelong political activist.

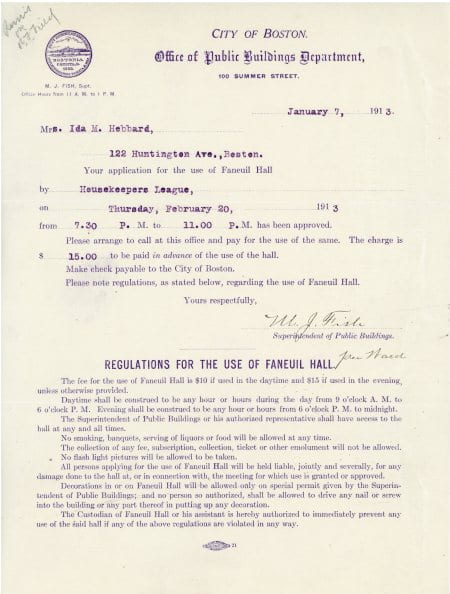

Ridley raised awareness about race relations; her contemporary Ida Hebbard pioneered the issue of food safety in Boston. Recent documentaries like Food, Inc. and Cowspiracy have challenged people to think about where their food comes from. Hebbard became a food safety activist over a hundred years ago.

She served as president of the Housekeepers League, an all-female group. During the 1910s, the League lobbied for consumer rights, protesting the increasing prices of household foods. Hebbard led the group in protesting the price of eggs in 1912, as well as the price of potatoes and coal in 1917. Potato prices for consumers dropped from 70 cents to 35 cents a peck because of their efforts. More importantly, she advocated for the Bob Veal Bill. This bill banned the sale of calves weighing less than sixty pounds, preventing them from being slaughtered and shipped to Boston the day they were born.

In November 2016, activists like Ida Hebbard succeeded in passing Question 3 on the ballot, which banned the confinement of farm animals in small cages in Massachusetts. Like the Bob Veal Bill, Question 3 will go on to improve the health of people because it improves the lives farm animals.

Grace Lonergan Lorch, the third Boston woman featured today, championed civil rights and women’s rights in education. Before 1953, Boston Public School teachers were forced to resign before they married. Thus, in the 1880s, Florida Ruffin left her job to marry. Grace Lonergan Lorch changed that for future female teachers. In 1943, she brought a case against the Boston School Committee (BSC) in an attempt to keep her job after she married Lee Lorch. Although the BSC upheld the rule and Lorch was forced to resign when she married, the publicity surrounding the case forced the BSC to end the ban of married women public school teachers ten years later.

During his service in the military during World War II, Lee became aware of racism. During troop transports, he noted, often the black company had to clean the ship. Discrimination made Lee Lorch, a professor and mathematician, very uncomfortable and his wife shared his views. When the couple moved to New York City following the war, they worked to desegregate their home community, Stuyvesant Town apartments, which had banned black families from living in their complex.

Lee led the Town and Village Committee to End Discrimination in Stuyvesant Town to try to end the ban. In 1949, the Lorch family attempted to find a loophole in the ban and invited a black family to live in their apartment as their “guests.” When their plan backfired, the couple and their daughter, Alice, moved to Pennsylvania, then Tennessee before they moved to Little Rock, Arkansas in 1955.

The couple became very active in civil rights in their new community. Their neighbors were Daisy and L.C. Bates, founders of the Arkansas State Press and active members of the NAACP during the Little Rock Crisis. Alice Lorch became friends with many of the children in their new neighborhood. So, in September 1955, Grace wrote to the local superintendent requesting that her daughter be able to attend the local school. She hoped that Alice would not only be able to attend school with friends, but also promote integration as their neighborhood was predominately black. Although the school board denied her request, Grace continued to be involved in Little Rock’s branch of the NAACP.

On September 4, 1957, Elizabeth Eckford, one of the Little Rock Nine, found herself alone and surrounded by a mob when she attempted to enter Little Rock Central High School.

All nine teenagers had planned to arrive at the school together with their parents, but the meeting place changed. The Eckford’s lack of a phone left Elizabeth uninformed and alone. Grace Lorch, after dropping Alice off at school, passed the high school and saw Elizabeth’s predicament. The civil rights activist fought her way through the angry crowd and helped escort the girl home. The rescue of Elizabeth placed a target on the Lorch family. Alice Lorch found herself bullied at school. Someone placed dynamite in their garage, and they were harassed by both press and the people around them. In 1959, Lee accepted a job from the University of Alberta and moved his family to Canada.

By fighting for causes that were important to them, Florida Ruffin, Ida Hebbard, and Grace Lorch shaped the future and women now continue to do so. Originally from Little Rock, journalist, activist, and speaker Liz Walker became the first African American woman to co-anchor a newscast in Boston in the 1980s. Lauren Singer challenges us to think about where our household goods come from and the environmental impact they may have. In India, Rashmi Misra fights for education in rural communities and giving young women entrepreneurial skills, and Maya Wiley works for civil rights in New York. Like Ruffin, Hebbard, and Lorch before them, these women will go on to influence the next generation of women.

Monica Haberny is currently working on her Master’s degree, specializing in Archives. She received her Bachelor’s in History from Montclair State University (2013). Currently, she is working on a digital exhibit on Kathleen Sullivan, the only woman on the Boston School Committee during the start of Boston’s public school integration, for Stark & Subtle Divisions. She has a strong interest in the history of nutrition, activism, and animal rights, and hopes to use these interests in her final capstone project.