By Corinne Zaczek Bermon

To learn about how her family and tutors influenced Rose Nichols, read Part I.

In this second post exploring the world of Rose Standish Nichols, we begin with those who impacted her life and end with her tutelage in landscape architecture.

Rose Nichols was highly influenced by her parents, Arthur Howard Nichols and Elizabeth Homer Nichols, and her two younger sisters, Margaret and Marian, as they grew into adulthood. Arthur Nichols grew up in Boston’s North End; he graduated from Harvard College in 1862 and Harvard Medical School in 1866. Arthur Nichols did not grow up in a Brahmin family, but rather as part of the well-educated middling class. His entrance into Harvard College allowed him to enter into the upper class, by facilitating his marriage into such a family. Arthur Nichols loved to travel in Europe, a passion he passed onto Rose, and as a single man, he continued his medical studies in Paris, Vienna and Berlin. In 1869, he married Elizabeth Fischer Homer from the prominent Homer family in Roxbury Highlands,

Massachusetts. Arthur became a renowned holistic doctor in Beacon Hill, practicing in the family home at 55 Mount Vernon Street and for several decades was the “summer doctor” at Rye Beach, New Hampshire, where the family spent their summers before buying a home in Cornish, NH.((B. June Hutchinson, “Macdaddy Doodadle, Doodadle Macdade, Mactaddy Doddadle Day” The Nichols House Museum and Archive. http://www.nicholshousemuseum.org/pdf/nichols_family/macdaddy_doodadle.pdf.))

Aside from her parents, Nichols tutors in landscape design also influenced her social activism. Nichols was only eighteen when her family bought their summer home and from the very beginning, Nichols’ uncle, the famous sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, pushed his favorite niece to take up garden design after admiring the walled

garden she created at the Nichols’ Cornish, NH summer home, dubbed Mastlands, in the Cornish Colony. In 1889, after the family had purchased Mastlands, Saint-Gaudens introduced Rose to Charles Platt, a self-trained architect and landscape architect. Platt was one of America’s most influential 20th century designers and was influential in the emergence of the style Beaux-Arts, which Nichols favored throughout her career.((Cynthia Zaitzevsky, Long Island Landscapes and the Women Who Designed Them (New York: WW Norton &Company, 2009), 200-203.)) Along with Saint-Gaudens, Platt encouraged Nichols to travel the world and study gardens in many European countries. Studying with Platt led Nichols to study drafting and lessons in horticulture from Benjamin Watson at the Bussey Institute at Harvard, located adjacent to the Arnold Arboretum in the neighborhood of Jamaica Plain. At the Bussey Institute, Nichols was encouraged to study in Paris at Ecole des Beaux-Arts.

Perhaps the most influential of her landscape design mentors was H. Inigo Triggs in London. Rose set sail on the SS New England on 27 February 1901 for Liverpool, England with friend, Ellen Cushings and traveled to London to become Triggs’ apprentice.((Arthur Howard Nichols papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.)) Triggs, already an acclaimed landscape architect by the time Nichols joined him in London, had built his career on designing formal gardens and

country houses and specialized in historical research to re-create gardens of the past. During her tenure with Triggs, Rose Nichols finished her research and wrote English Pleasure Gardens, published 19 November 1902.((Ibid.))

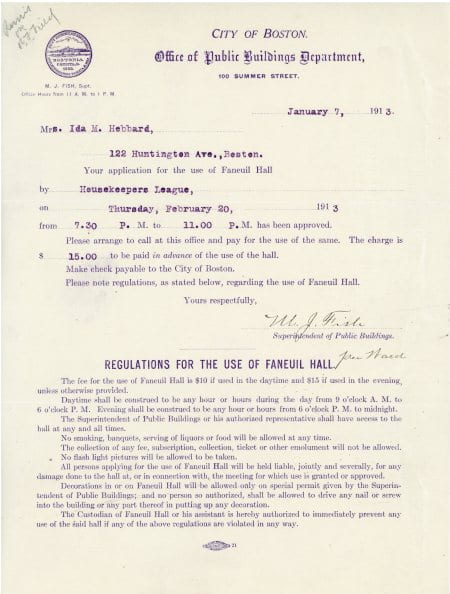

It was under Triggs that Nichols began to connect landscape design and city planning to her vision of world peace. Triggs gave a brief review of the great awakening throughout the world in city development in his book, Town Planning, Past, Present and Possible, which he was working on from the time Nichols apprenticed with Triggs until its publication in 1910. Triggs gave special consideration to small parks, claiming that peaceful public spaces led to a peaceful state of mind for city dwellers.((H. Inigo Triggs, Town Planning: Past, Present and Possible. (London: Methuen & Co, 1910), 12-15.)) Triggs, himself a pacifist, instilled in his pupil the idea that the promotion of peace did not only have to come in the form of marches and campaigns but through the designing of landscapes, parks and gardens. When Nichols returned from her apprenticeship with Triggs in June 1903, she had adopted this idea, and over the next fifteen years she would use this principle as a way to promote her peace agenda in Europe. In the same year of her return, Nichols became the first woman listed under the heading of “landscape architect” in the Boston City Directory, and she kept an office at 5 Park Street downtown while she began traveling between New York, Boston and Chicago working on various projects. Early in her career, Nichols received commissions in Lake Forest, Illinois; Boston; Massachusetts; Long Island, New York; and Newport, Rhode Island. Her reputation grew and she worked in more distant areas such as Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Augusta, Georgia; Tucson, Arizona; and Santa Barbara, California by the 1920s. Her work was especially valued by her patrons in the Southwest, since her travels to arid Spain in her youth and with the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom gave her a special knowledge in solving problems that were inherent to making a successful garden in a desert.((Mary Bonson Hartt, “Women and the Art of Landscape Gardening,” The Outlook, vol 88, No 13, (March 28, 1908), 702. https://books.google.com/books?isbn=078648733X))

In the next segment, we will learn about Rose Nichols’ work in the Woman’s Peace Party and WILPF during and after World War I.

To learn more about Rose Standish Nichols, visit the Nichols House Museum and take a tour!

Corinne Zaczek Bermon is earning her M.A. in History with a specialization in Archives. She earned a B.A. in American Studies in 2009 and a M.A. in American Studies in 2015 from University of Massachusetts Boston. This series of articles on Rose Standish Nichols represents her award winning research in American Studies. Currently, her work explores the social history of the Otis Everett family living in the South End of Boston in the 1850s. She is designing a digital exhibit that explores Victorian life for the merchant class conducting business in Boston and abroad through the Everett letters.