Speakers Kathryn Hyer, left, and Pamela Herd, right, who were introduced by Professor Edward Miller, center.

Any celebration of an important anniversary should honor the past and also look to the future. So it was at the Gerontology Institute’s 35th anniversary symposium held on campus last week.

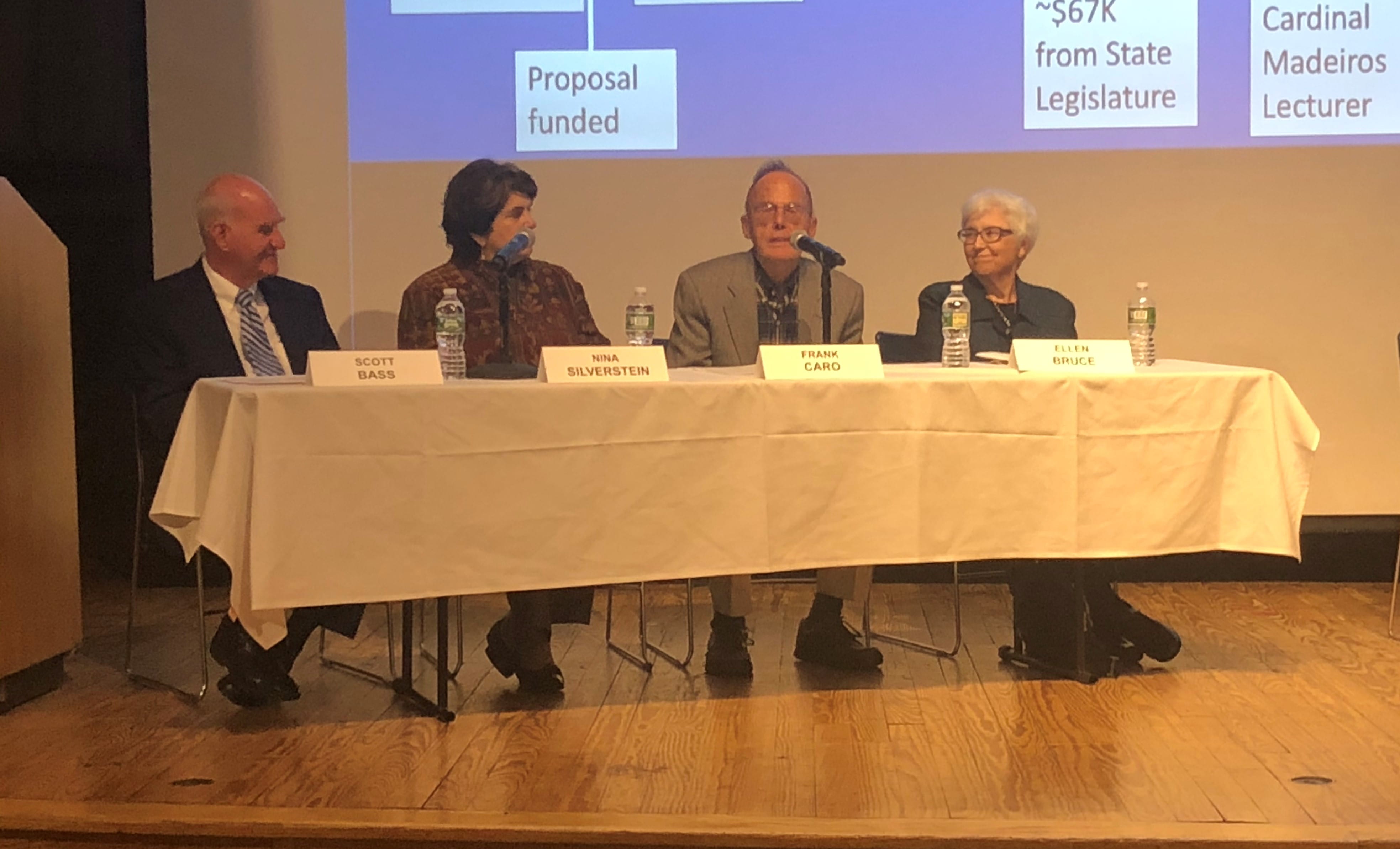

A panel of founders and other past leaders of the gerontology program at UMass Boston described the formative years of the institute and the gerontology academic department. They were joined on the Snowden Auditorium stage by the current directors of four Institute centers, as well as two academic program leaders, who discussed their more recent achievements and current priorities.

Later in the symposium, two other speakers turned to the future of gerontology. University of South Florida professor Kathryn Hyer, the incoming president of the Gerontological Society of America, and Georgetown University professor Pamela Herd focused on issues they believed would be priorities for gerontologists in the years ahead.

Two videos of the symposium are available online. The first segment covers the initial panel. The second segment replays the comments and conversation of Hyer and Herd. (These files are streaming in a format not supported by Internet Explorer. Viewing with Chrome, Safari or Edge is recommended.)

Herd highlighted past policy reforms that never happened or were poorly executed, and their implications for the aging society over the next 20 to 30 years. The major themes: More risk and confusion among individuals when it comes to economic security and health.

On economic security, Herd pointed to the decline of defined-benefit pensions across America and how subsequent plans shifted investment risk onto individuals while making the process itself more complex. She also pointed to some elements of Social Security, such as marital survivor benefits, whose rules and requirements disproportionately limit access to some racial groups.

On health, Herd talked about the confusing array of Medicare insurance plans and benefits older adults must choose between annually. Two key examples: Growing Medicare Advantage plans and the large array of prescription drug options available in most states.

“The worlds of navigating retirement income, health insurance and health care have become so much more complicated than they were,” said Herd. “I think this has real implications for people in later life in terms of quality of health insurance and income security, not to mention the kind of stress people will face.”

Hyer focused on three issues she believed would be high-priority gerontology challenges related to health and well-being in the years ahead: The ability to integrate older adults into the community, the adoption and understanding of technological advancement and efforts to mitigate the effects of climate change.

She described the global age-friendly movement as “contagious and growing,” a development to capitalize on in the future. Hyer highlighted many promising technology developments that could help older adults and the eldercare workforce, but raised concerns about affordability and the appropriate integration of new products with services provided by people.

Hyer, who is director of the Florida Policy Exchange Center on Aging, also pointed out how older adults were particularly vulnerable to extreme weather conditions related to climate change.

One example: The 85 people who died in the first day of fire in Paradise, Calif., last year. Among them, 70 were over age 65 – a total that amounted to 82 percent of fatalities, she said.

Hyer’s message: Better preparation for older adults in such cases can save lives. “I don’t want to be pollyannaish about climate change, but I want us to understand we can work on it,” she said.

Earlier in the symposium program, Scott Bass described the creation of the Gerontology Institute and the securing of state funding that made it possible.

Bass, the founding director of the UMass Boston gerontology program, also described policy research and analysis projects that raised the institute’s early profile.

“We built a foundation and it was a bit precarious,” said Bass. “It was never easy, but we persevered.”

Professor Nina Silverstein described the history of the program’s Frank J. Manning Certificate program, which now counts more than 1,000 alumni and was a driving force behind many action research projects that influenced public policy over decades.

Former Institute Director Frank Caro originally came to UMass Boston in 1988 as the institute’s research director. He discussed efforts at that time to develop a more professional research agenda and a faculty to lead a gerontology PhD program on campus. As institute director, Caro also oversaw the development of what would become the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at UMass Boston.

Ellen Bruce, also a former institute director, came to the program in 1988 as policy director. Her early priority: Make sure the institute was doing the kind of research that would really inform policies that were demanded at the time. Over time, she found the integration between policymakers and academics an interesting challenge — bringing together people with different approaches and priorities.

That combination remains a key element of what makes the institute special today, said current Director Len Fishman.

“We all grew out of what Scott and his colleagues founded,” said Fishman. “The integration of academic enterprises and applied research and policy analysis was baked in from the very beginning. It’s absolutely essential to our identity and, in some ways, has set us apart.”

Leave a Reply