Bill McKibben is an environmental activist and author of Falter: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out? Thirty years ago, he wrote The End of Nature, one of the earliest warnings of climate change for a mainstream audience. Like most writers, Bill is an introvert, and he was slightly uncomfortable on stage at the Brattle Theatre in Cambridge on April 17th. He was clearly tired, and who can blame him? It was nearing the end of his book tour and he comes with grave news: “the end of nature” was too cheerful of a title.

Scientists were conservative in their predictions of climate change thirty years ago: now, there is half as much sea ice in the arctic during the summer months, the ocean is 30% more acidic, and the great barrier reef is half dead. By the middle to end of the century, land that people have been farming for thousands of years will be barren, billions of people won’t be able to survive outside in the heat for more than a few hours, farms anywhere near the shore will be salt fields, and entire communities will be submerged. We have taken the physical stability of the planet for granted.

As one of the founders of 350.org, Bill knows that planet-wide collective action must be both educational and confrontational, but the fossil fuel industry has invested billions of dollars in lying to control the climate of opinion and keep the infrastructure of the world as it is.

Thirty years ago, when Bill first warned us about what was happening, we might have made a lot of small changes to alter, rather than falter, our trajectory. Now, only a radical environmental movement can save us from extinction.

Nicholas Trefonides: I read in Falter that you took a trip to the Greenland ice shelf last summer, and you were with veteran ice scientists and two poets, Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner and Aka Niviana. You say, “Science and economics have no real way to value the fact that people have lived a millennia in a certain rhythm, have eaten the food and sung the songs of certain places that are now disappearing. This is a cost only art can measure, and it makes sense that the units of measurement are sadness and fury—and also, remarkably, hope.” Can you talk more about working with artists and the role that art could play in the environmental movement?

Bill McKibben: I think it’s crucial. 350.org has long had an artist in residence, David Solnit, and his passion is turning large numbers of people into part-time artists. Environmentalists have been pretty good at appealing at the part of the brain that likes bar graphs; not so much the other hemisphere.

NT: You said renewable energy sources like solar and wind would disperse global power and balance much of the wealth inequality. Could a renewable future also be post-industrial, and do you think a network of small, community-based governments would be more sustainable in the long run? How do you see renewable energy as a source of environmental and social healing?

BM: I think it puts us on a trajectory toward a more localized and more democratic energy system, and this will correct some of the power and wealth imbalances on the planet, but trajectory is mostly what I worry about—my best thoughts on an optimum outcome are in the last part of Deep Economy, but I don’t spend much time on it.

NT: In Falter, you mention a study that found a French person sees more photos of a lion in a year than there are actual lions left in West Africa. The internet enables organizations like 350.org to reach more people around the world, but it often disconnects us from what is near and dear. How did our emotional relationship with nature go awry?

BM: Screens were certainly a big part of it, beginning with tv (I wrote a book on this once too, The Age of Missing Information). But now it’s accelerated insanely with the internet.

NT: For a while, fossil fuel corporations broadly claimed that their business was in energy. But it was, and still is, just about carbon. In Falter, you mention an interaction with a fossil fuel lobbyist at the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. In terms of the human game, do we need to distinguish between scientists, policy makers, and lobbyists when we’re all just people, climate deniers or not?

BM: I think the forces are larger than people—empowered corporations are the problem, because without effective regulation they have no real off switch. And we’re seeing the results of that.

NT: You’ve said that if Ayn Rand had focused on writing essays and manifestos, then she would have been dismissed as a crank and forgotten. But instead, she wrote stories. Can you talk more about the danger of melodrama and also Rand’s long-term influence in Washington?

BM: She’s immensely powerful because her ideology appeals to the powerful and the rich—it glorifies them at the expense of everyone else, and turns their greed into an ideology, albeit a dumb one.

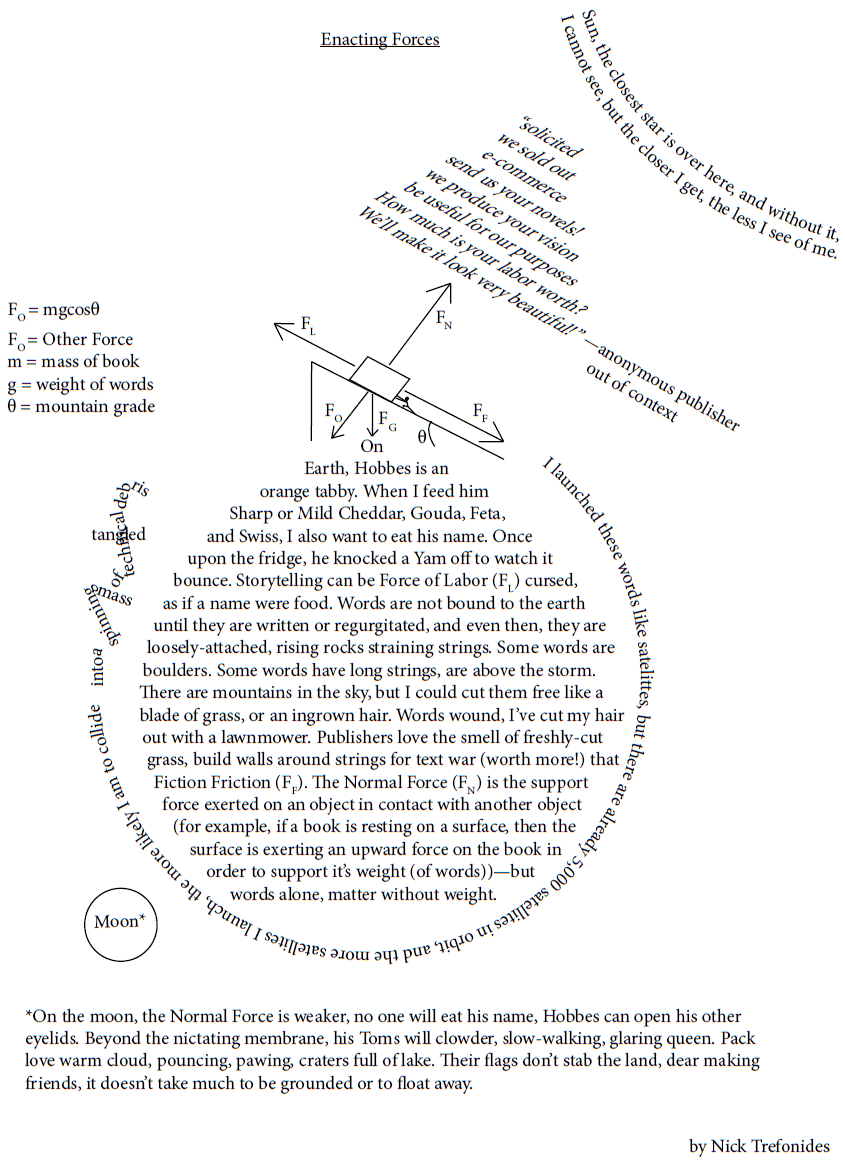

NT: Could storytelling be used to reverse or counteract some of the damage, and would these stories be hopeful or apocalyptic?

BM: There’s an increasing amount of good storytelling going on, fiction and fact. Check out everyone from Kim Stanley Robinson to Naomi Klein, Margaret Atwood to Rebecca Solnit. It’s crucial. A new metaphor is as useful as a new engine design.

NT: You said that artificial intelligence is where climate change was thirty years ago, back when you wrote The End of Nature. With computers having brainpower surpassing that of humans, we could also be witnessing the end of human nature. What limits should we create as AI technology and genetic engineering develops? Is it possible for the ethics community to keep pace?

BM: It’s very hard, especially with the huge amounts of money on the line. The germline should be the red line for genetic engineering; for AI it’s harder to say with specificity, though a kill switch on everything seems like an awfully good start.

NT: Computers are already producing art, fooling concert hall audiences and selling at auction houses, because they can analyze what we like and reproduce it. I like to think of art as the process of making, that is, making something new, something that people didn’t know they found beautiful until the artist created it. Poetry is sometimes described as the embodiment of a human feeling that, until the point that the poem was written, hadn’t been put into words. This question might come down to whether or not you believe the future can be entirely determined by analysis of the past, but how are computers creating art if they aren’t conscious and can’t act intuitively?

BM: They aren’t creating art. They’re just mimicking things others have done—art is the reflection on the condition of being human.

NT: Why does the environmental movement require the breaking of binaries like progressive and conservative?

BM: Because it’s going to take a huge majority of us to finally gets done what needs doing!

Technological innovations in renewable energy systems such as the solar panel seem to give Bill hope. It’s magical to him that we can face a piece of glass to the sun, and then out the back flows the now mundane modernity that was introduced by industrialization. The fossil fuel industry and “conservative” politicians (who Bill points out have surprisingly little interest in conservation) are obviously scared of a postmodern era in which “power” is freely available. Trump recently signed two executive orders, one that keeps people from slowing down the construction of pipelines and another that stifles the fossil fuel divestment movement. The environmental movement will not move fast enough unless it operates through a network of communities that can proliferate sustainability as a form of liberation.

At the talk in April, Bill said he has hope that the climate crisis will occupy more of the political conversation. But then in July, during one of the recent democratic primary debates, the moderator asked only one question about the climate crisis, and most of the candidates didn’t have detailed plans. They are clearly in denial that business as usual will lead to starvation, disease, and even war. A sustainable initiative must bring renewable energy infrastructure to small communities, but localization of energy is converted to political power that depends on previously imagined lines around continents, countries, states, cities, and countless jargon.

Bill more than admits that the profitable growth imperative of capitalism is accelerating global warming into what is now accepted as an “Anthropocene” or a climate “crisis, ” but he also acknowledges what he calls the “failed soviet experiment” of state-led communism. For the past several decades, we’ve been acting hyper individually, believing that markets would solve everything.

When the climate “debate” (perhaps the debate is the crisis) began, the first thing we were told was to take individual action, but that didn’t work, and now, we must either engage in sociopolitical reassembly or prepare for social collapse amid extinction and political upheaval(s). We need collective action from small communities working towards a common faith, what Bill might call “human solidarity.”