By Brian Wright O’Connor

The tall priest in combat boots and a camouflage chasuble leans forward and places both hands in blessing on the bowed head of a GI in a trench. Other soldiers, their weapons set aside, await his benediction. They stand in the curved trench-line, framed by the blasted trees and scarred earth of the battlefield.

The tall priest in combat boots and a camouflage chasuble leans forward and places both hands in blessing on the bowed head of a GI in a trench. Other soldiers, their weapons set aside, await his benediction. They stand in the curved trench-line, framed by the blasted trees and scarred earth of the battlefield.

The photographer, holding a battered black Leica, peers through the viewfinder, ready to shoot. The rim of his helmet is pushed up on his forehead.

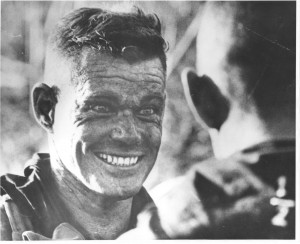

The soldier grins through the dirt of combat into the face of a fellow infantryman. A black scarf hangs loosely around his neck, streaked and grimed. The morning light shines off the side of his face. His eyes, alive and intent, welcome survival.

Three men, three images of war from the Central Highlands of Vietnam, 80 miles north of Saigon near the Cambodian border. Their lives converged briefly in December 1967 at a defensive base about three kilometers southeast of the remote village of Bu Dop, where, unbeknownst to them, North Vietnamese troops were staging incursions into the Republic of South Vietnam in preparation for the Tet Offensive the following month.

What happened there did not change the course of the war but it unalterably changed their lives. The ripples of that conflict, 44 years later, move slower now than when automatic gunfire cracked through the trees and mortar rounds fell in chilling arcs. But move they do.

The soldier, 37-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Mortimer Lenane O’Connor, air assaulted into the landing zone on December 6, jumping off the Huey helicopter on a cleared-out patch near the Bu Dop airstrip used by a Special Forces outpost.

O’Connor had taken command of “the Black Scarves” of the 1st Battalion, 2nd Infantry Regiment of the storied U.S. Army First Division just six weeks before. He arrived with about 500 men under his charge – three rifle companies, artillery, reconnaissance and heavy weapons platoons, and support staff. Back in the U.S., his wife Betsy and six children awaited his return. My mother knew Mort didn’t fly halfway across the world just to keep his head down, do his duty, and get his ticket punched for promotion up the ranks. He was a gung-ho infantry officer, a West Pointer with a sense of gallows humor who believed that large-force engagements were the quickest way to conclude the war. In other words, kill as many of them in direct action as possible. “It’s a lousy war,” he said to a friend over the telephone before he left, “but it’s the only one I’ve got.” Among the men of the Black Scarves, also known as the Dracula Battalion, his call sign was “Drac 6.”

Horst Faas, 34, had already won a Pulitzer Prize for his work in Vietnam when, alerted at the AP bureau office in Saigon about action near the border, he landed at Bu Dop. Faas grew up in grim post-war Germany and had covered war in the Congo and Algeria before arriving in Vietnam, his third assignment in the crumbling French empire of overseas colonies. He was compact and tough and unafraid – an inspiration to the stable of photographers he mentored during his 10 years as the AP’s photo bureau chief in Vietnam.

Horst Faas, 34, had already won a Pulitzer Prize for his work in Vietnam when, alerted at the AP bureau office in Saigon about action near the border, he landed at Bu Dop. Faas grew up in grim post-war Germany and had covered war in the Congo and Algeria before arriving in Vietnam, his third assignment in the crumbling French empire of overseas colonies. He was compact and tough and unafraid – an inspiration to the stable of photographers he mentored during his 10 years as the AP’s photo bureau chief in Vietnam.

Father Arthur Calter, the son of a church sexton and laborer, was 36 when he followed his two priest brothers into service as a military chaplain. Less than a year after leaving behind his family in Boston and the comfortable parish of St. Francis Assisi in Braintree, he was wearing a Black Scarf along with his vestments, saying Mass and hearing confessions in hostile territory. Over the PRC-25 radio, the battalion knew the priest was on the move when they heard the call-sign “Drac 19.”

Mort O’Connor’s version of events at Hill 172 in Bu Dop exists in dry after-action reports, filled with numbers denoting enemy dead and wounded, weapons captured, and his own battalion’s casualties during the search-and-destroy mission known as Operation Quicksilver. It also survives in media accounts and letters, written nearly every day, to Betsy, living in Tucson, Arizona, close to Mort’s father, a retired West Point general, and his mother Muriel. On December 9, after an unusual three-day break in communications home, Mort wrote, “On the afternoon of 7th, we made contact with a small NVA unit; that night we received a heavy attack from two battalions, the 1st and 3rd, 173rd Regiment, NVA.”

Those two clauses, separated by a semicolon in Mort’s urgent but grammatical scrawl, tersely summarize three days of action, including an all-night assault on the battalion’s perimeter which nearly resulted in the enemy breaking through to overrun the outmanned U.S. position. Later intelligence reports showed that the attacking regiment was the 273rd – a seasoned Viet Cong force that fought the Americans from the outskirts of Saigon to the Cambodian border throughout the war.

Those two clauses, separated by a semicolon in Mort’s urgent but grammatical scrawl, tersely summarize three days of action, including an all-night assault on the battalion’s perimeter which nearly resulted in the enemy breaking through to overrun the outmanned U.S. position. Later intelligence reports showed that the attacking regiment was the 273rd – a seasoned Viet Cong force that fought the Americans from the outskirts of Saigon to the Cambodian border throughout the war.

The action for Faas began as soon as he stepped off the helicopter from Saigon. He had been to Bu Dop before to dodge the snapping of bullets through the thick bamboo stands – one of the many positions that went back and forth between enemy and U.S. hands during the long conflict. Haas spent the day of December 5 with the Black Lions of the 28th Regiment, another battalion of the Big Red One deployed to Bu Dop to conduct search-and-destroy patrols around the Special Forces camp and airstrip. He hunkered down at night within the crowded command post, putting a bit of cover over a hastily dug bunker. “In the middle of the night, the command post came under rocket attack – there were four or five fatalities and much damage from two or three well-executed attacks from several sides. It was obvious that the enemy were determined and numerous,” he told me in an interview several years ago from his home in London.

The next morning, Faas caught a ride two kilometers south to the position being dug by the Black Scarves on the only high ground in the area. He walked inside the perimeter, snapping photos within the 50-meter zone where soldiers spent as much as six hours digging foxholes from the red basalt clay. “I met the colonel that morning. He wasn’t happy to see me,” said Faas. There was no touch of the romantic around Mort that day, no hint of the Ph.D. candidate from the University of Pennsylvania or a passion for Beowulf and Old English tales of berserkers and monsters lurking in the dark. “I asked if I could stay in the command post, but he said it would be too crowded and that I had to dig my own hole. I’d already been in Vietnam five years and usually got a better reception.”

Haas left the Night Defensive Perimeter under construction and walked out toward the wire, where he spotted Father Calter saying Mass to the boys in the trench. He took photos of the tender exchange between the Boston priest and the wary soldiers and later wrote about it in an AP story that ran on the wire: “The chaplain stood in the open and recited Mass. Huddled in trenches, men of the U.S. First Infantry Division looked toward him and listened. They wore their combat gear. They were filthy, covered with the red dirt that covers everything here. ‘This will be a different Christmas than you have had before,’ said Chaplain Arthur M. Calter of Boston. ‘There will be no jingle bells, no Christmas trees. But don’t forget, Christ is with you in these trenches.”

Calter, a gregarious cleric and a gifted Irish baritone, now lives in a high-rise for retired priests in the old West End of Boston. His days of hitting overhead smashes on the tennis court and snatching melodies out of the air on battered parish pianos are long gone. His eyes narrowed as he looked back over nearly half a century to that battlefield where cordite hung in the air like fear and incoming rounds sent men ducking in their trenches. “I told them to stay there while I said Mass in case anything happened,” said Calter. “The place was so uncertain and hot. I was exposed but tried to be as careful as possible because, let’s face it, I was a perfect target.”

Calter looked around the small sitting room, bordered by a sliding glass door with a view of the ether dome of the nearby Massachusetts General Hospital. “I used to have a picture around here,” he said, his voice trailing off. “During one Mass, a mortar round came in and exploded nearby. I went flying through the air and someone got a picture of me looking like superman with my chasuble stretched out behind me like a cape.”

Back at the command post, O’Connor received radio reports of enemy contact. His reconnaissance platoon spotted several scouts within a kilometer of the Night Defensive Perimeter. It was impossible to tell whether they were Vietcong, local communist militia, or soldiers of the North Vietnamese Army. All he knew is that they were coming in for a look. He urged his men to dig in faster, set up the battery of four 105 mm Howitzer cannons, and to string barbed wire at the perimeter, just inside the listening posts set up to monitor enemy movements.

Intelligence reports came in identifying the presence of troops from the NVA’s 271st Regiment, which were launching mortar and rocket attacks against the Special Forces camp. Returning from their security sweep, the Delta Company commander informed O’Connor that the lead element of the Recon Platoon had made contact with an enemy patrol that was observing the battalion setting up the NDP. The firefight resulted in a recon soldier being wounded in the leg, but the VC patrol was chased off.

Hours after taking the picture of Calter saying Mass, Faas was following a patrol among the rubber trees of the old Michelin plantation when a rocket-propelled grenade exploded nearby, spraying his legs with shrapnel. A medic was called immediately. When he reached the photographer, both of Faas’s legs were spurting blood. The right leg was badly hit above the knee. The medic applied a tourniquet and struggled to find a vein for an injection of albumin, which helps stanch blood loss. “Will you hurry up with that?” asked Faas, whose face had turned an ashen grey. Within 20 minutes, an evacuation helicopter landed in a nearby clearing.

Father Calter, alerted to the evacuation, rushed to the landing site. “They couldn’t wait to pick up the wounded and the dead after the fighting. They had to evacuate immediately to save the wounded,” said Calter. “I was never far from the medics.” Arriving at the helicopter, Calter grabbed one of the stretcher poles and helped load Faas onto the aircraft. “He was hurt pretty bad but conscious. I remember him saying he’d send the pictures to me when he landed.” Faas was dusted off to the hospital at Long Binh, the headquarters of the U.S. Army’s Vietnam command located 30 kilometers outside Saigon. “Sure he was hurt, but he didn’t ask for last rites. I didn’t do that a lot anyway. I would pray with the soldiers but even if it they were badly wounded I wanted to give them some hope of surviving.”

Calter continued to follow the medics, moving around the battlefield. But the enemy had withdrawn. By late afternoon, the priest was back at the NDP, finishing his foxhole. The battalion settled in for the long night.

The battalion commander called in the patrols. Shortly after nightfall, troops out on the LP heard enemy movement but it was difficult to establish their positions without compromising their location. They reported the VC digging in approximately 100 meters from the perimeter. The prospect of a large-force engagement was unusual in other parts of the war zone, but not at Bu Dop, where three major ground attacks at defensive positions had already taken place. Throughout the fall of 1967, the NVA persistently pressed attacks in the face of significant defensive advantages and overwhelming U.S. firepower, including artillery at Fire Support Bases, helicopter gunships and strafing F-4 fighters armed with rockets and bomb. As the clock ticked toward midnight, the battle at Hill 172 would provide another example of the enemy’s deadly intent.

The clash began in the first hour of December 8 with a barrage of 122 mm rockets launched into the NDP from all sides, quickly followed up with mortar and RPG rounds. Anticipating a ground assault, O’Connor ordered the listening post and ambush patrols to come into the NDP. The first U.S. casualty was taken when one of the LP soldiers was killed trying to return to the perimeter.

The first attack occurred at Charlie Company’s position on the northeast, with a smaller force leveled at Delta Company to the south. Bunkers armed with .50 caliber machine guns opened with full automatic fire on the onrushing enemy, which came in wave after wave of hundreds of troops. For three hours, the North Vietnamese charged the NDP, keeping up a withering barrage of 60 and 80 mm mortars, 75 mm recoilless rifles, and RPGs along with AK-47 assault rifles. O’Connor called in support from helicopter gunships and artillery from the Fire Support Base, directed by an artillery forward observer.

At one point, the battalion commander left the command post to check the men positioned on the berm of earth built along the rim of the NDP. In his absence, a mortar round hit the dirt piled around the bunker. The battalion’s operations officer took a piece of shrapnel to the helmet but it didn’t penetrate. O’Connor quickly returned, surveyed the damage, and continued to direct operations.

The attacks persisted. Finally, O’Connor ordered the muzzles of the 105 mm Howitzers lowered and filled with explosive charges. As the next waves of enemy charged the wire, the cannons, their barrels parallel to the ground, fired like giant shotguns into the wire, stopping the attack in its tracks.

The enemy assault ceased. Battalion soldiers heard movement along the wire and beyond but held their own fire. As dawn broke over the charred and smoking battlefield, the Black Scarves saw enemy dead hung in the wire and strewn over the landscape.

Faas had already been airlifted but another photographer, the UPI’s Kyoichi Sawada, remained with the battalion throughout the night. His iconic black-and-white images of the clash at Hill 172 depict broken bamboo stumps, blackened terrain, and men tensely holding weapons through the roar of gunfire and muzzle flashes. His photo of a maniacally happy Mort O’Connor never made the wire – what did was a photo of the battalion commander, a cigar between his teeth, frisking a young prisoner. Sawada’s radio report to the UPI spurred news agencies throughout Saigon to load up for a trip to Bu Dop.

“The morning of the 8th – in fact all day – we patrolled and policed up bodies and prisoners,” wrote Mort. “So far we’ve found 48 dead and captured 6 POWs. The battalion lost 4 killed in action and 14 wounded. We figure, based on intelligence reports and PW interrogations in the past, that we probably killed another 50 and wounded 100. In other words, we’ve effectively decimated one-half of two battalions.”

Interrogations also revealed that the enemy, blocked by the Delta Company’s security sweep, was unaware that six lines of concertina wire had been strung around the battalion position – a formidable barrier to a night-time charge.

Chief on their minds of war correspondents rushing to Bu Dop was not the narrative of the engagement, but rather getting visual confirmation of enemy dead. Reports of inflated body counts in order to mollify the anxious public and Pentagon brass about the positive prosecution of the war were already circulating in the press. Initial reports of a large count of enemy dead needed to be confirmed.

Well before noon, “we had a lot of reporters,” wrote Mort. “They came up to interview us, look at the war booty – 16 AK-47’s, four light machine guns, three rocket launchers, and huge quantities of rockets, small arms and mortar rounds. Most of all, they wanted to see the bodies – there is a great suspicion about body count, but we had 48 to be seen.”

CBS footage of interviews and images remained locked in the network archive until former General William Westmoreland sued “60 Minutes” over its claim of his complicity in enemy body counts. A call to CBS in 1988 yielded videotapes of the footage, which had been catalogued in preparation for the trial. More than 20 years had elapsed since the aftermath of the Battle of Bu Dop.

The footage shows a visibly nervous CBS reporter Bob Schackne interviewing Mort O’Connor and Regimental Commander Col. George “Buck” Newman within yards of the carnage. B roll shows captured weapons, prisoners, stacked bodies and an airlift of the enemy dead by a Chinook helicopter carrying them away on a web sling attached by cables to the aircraft. “These were living, breathing men yesterday,” says Schackne in the voice-over. “Today, there are just a sanitation problem.”

“Very often after a major battle, it’s hard to tell who won and who lost,” continues Schackne, standing to the side of O’Connor and Newman.

“But in this battle, the evidence of victory is very clear. Why was this battle so one-sided?” he asks O’Connor.

Mort, standing with his right arm over an M-16, his face shielded from the sun by his angled helmet, clears his throat. “A number of reasons. First of all, Charlie was above ground and we were below ground. That is, we had the advantage of defensive fortifications. The second reason is that we had magnificent fire-support. He can’t touch us when it comes to fire-support. Aircraft from the Air Force, gunships from the Army, all sorts of artillery – four-deuce, 105, 155, direct-lay 105 – plus the assets of my own battalion. A1 mortars, rifles, machine guns. He just can’t match us in firepower.”

Still nervous, Shackne rephrases the question, asking whether it was because of the firepower that the losses were so one-sided.

“Last night, the fact was that Charlie tried to do something stupid. He tried to overrun a tough position and when he does something stupid, he pays the price for it.”

The newsman then drills in on his real target – body counts. “Well, there’s often a lot of skepticism about the casualty figures, particularly about the claims we make about the damage we do to them because it’s so one-sided. In this case, there doesn’t seem to be any doubt about it,” he says.

O’Connor steps to his right in what appears to be a pre-arranged transition to the regimental commander’s boilerplate response about battlefield protocol to count enemy dead.

Parts of the footage ended up on the CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite. Newman, who had ordered the bodies airlifted because of the difficulty of digging a burial hole in the hard clay, had to answer for the gruesome images of VC being carted away like freight.

“The TV pictures are pretty gruesome and we were stacking them in a huge helicopter sling to carry them out,” wrote Mort. “They were carried over to district chief’s headquarters to be buried – I definitely didn’t want my people to fool around with the job; the ground’s too hard.”

“When – and if – you see the pictures on TV, don’t be concerned with the way I sound. I was quite hoarse. Also, and I hope it shows up, the kids in the battalion did a magnificent job. They are proud as hell of themselves and their confidence is way up, The assistant division commander said that this is the way Dracula used to perform all the time; the battalion is on its way up. Hell, it’s here!”

Less than 48 hours later, the Black Scarves had pulled out – on their way to the next battle farther south.

Horst Faas, recuperating in Long Binh, would spend six months in the hospital. On crutches and confined to the bureau for months, he eventually returned to the field and stayed in country another three years – not long enough to see the war’s end, but he knew it would come. “It was demoralizing to see the troops return so many times to the same ground,” he said. “Bu Dop, Hamburger Hill – occupied, taken, and abandoned over and over again.”

Faas went on to win a second Pulitzer Prize, this time during the conflict in Bangladesh, where he photographed gripping scenes of tortures and executions. In 1976, he relocated to London as AP’s senior photo editor for Europe, until his retirement from the news agency in 2004, still hobbled by his war wounds. In 1997, he co-authored “Requiem,” a book about photographers killed on both sides of the Vietnam War and was co-author of “Lost over Laos,” a 2003 book about four photographers shot down over Laos in 1971 and the search for the crash site 27 years later. He also organized reunions of his brave band of lensmen, who met in Ho Chi Minh City, Vienna, and other capitals over the years.

But he never forgot the men of the Black Scarves. He visited the medic who saved his life at his home near Geneva, N.Y., and wrote about his experience.

He died in May 2012, age 79, leaving his wife, Ursula, and one daughter.

Calter remembered the blood on the ground and the charred, lacerated bodies of the VC the night after the assault. “It’s seared into my memory,” he said. “We were in a daze, happy to be alive but not really feeling it. Looking over the battlefield, I asked myself, ‘Was it all worth it?” He left the battalion at the end of 1967. Before returning home, he visited Faas in the hospital. “He was in good spirits,” said Calter, “eager to return to the bureau and the field.”

The priest’s return to the U.S. was short-lived: he re-uped for another tour. Assigned to the 101st Airborne, Calter found himself visiting familiar terrain throughout the next two years.

“When I went back the second time and we were fighting for the same spots, I began questioning the wisdom of what we were doing there,” said Calter. “We just had to put the white flag up and give it all up at some point.”

His faith in the war already rattled by his first tour, Calter found little solace in the second. “I remember a battle where the Viet Cong couldn’t claim their bodies. There was such an odor it took a two-ton truck to move them all and I wasn’t even touched by it. I remember in the evening thinking, ‘What is happening to me?'”

An intelligence officer shared with him letters and photos found in the pockets of one of the VC dead. “It was pure poetry – writing about the flashes of gunfire in the night, the touch of his children. He wrote to his wife about the aromas of her cooking, the sounds of his children’s laughter. It made me realize those were men just like ours who were victims of circumstances.”

Calter left Vietnam for good in 1970. He spent two years in Germany, then several more at posts in the U.S. His last stop was close to home – Ft. Devens, Massachusetts. He became pastor of several Archdiocesan parishes in the Boston area before retiring in 2000.

“War sometimes comes to us and we have to respond,” said Calter. “But I’m all for reconciliation. It takes courage to do that.”

The Black Scarves continued on search-and-destroy missions in the Iron Triangle north of Saigon in the aftermath of the January Tet Offensive, coming in contact several times with elements of the forces that had attempted to overrun their camp in Bu Dop.

On April 1, 1968, while O’Connor was personally leading a patrol, the squad was pinned down by machine gun fire. “Mort, who was near the center of his battalion column, spontaneously moved up to the fight,” wrote his West Point classmate Bob Rogers. “Along with him moved his radio man with the distinctive tall antenna of the command radio set. As if waiting for that one unique target, a Viet Cong rose out of a spidertrap and fired at Mort. The burst of gunfire put an end to the special cadence of Mort O’Connor’s heart. He died instantly, imparting to his life in that moment a unity of purpose few men enjoy, doing what he had been born to do – leading men forward in battle.”

By the time the knock on the door came in Tucson, Betsy already knew. She’d been working in the house the day before. “I suddenly heard a shot and stood up. I went cold,” she said years later. “I just knew.”

Days later, he was laid to rest at West Point in a cold April rain. Nearby was the grave of his uncle, a First Infantry colonel killed in the World War II invasion of Sicily, who was one of four brothers to attend the academy.

His wife and children stood beneath a white canopy. Over the grave were bouquets of tropical flowers flown in from Hawaii, where he had been born at reveille at Schofield Barracks.

Seven soldiers in dress uniform snapped to attention and delivered three volleys from their M1 rifles. Brass cartridges bounced off gravestones.

Those volleys, reverberating through the rain and the huddled trees of the old burial ground, echo still.