April 19, 2016

by Cedric Woods

0 comments

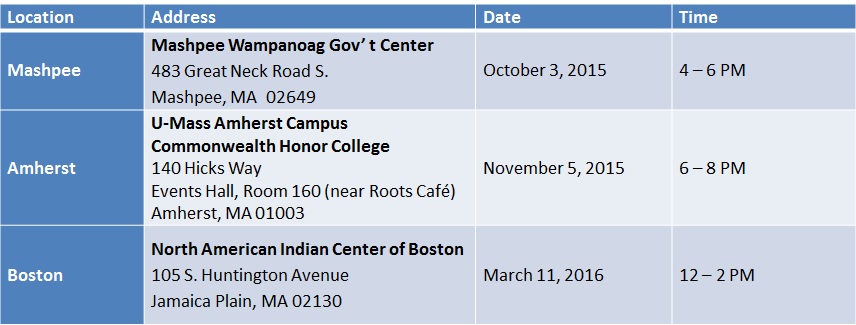

The last 9 months of Discussions For and With Massachusetts Native Peoples has provided richer dialogue, a multiplicity of perspectives, and greater participation than was ever expected.

With our last session held on March 11th at the North American Indian Center of Boston (NAICOB), we completed a very large circle. With our speakers at the event including the indigenous community to Boston, as well as urban indigenous Peoples from all corners of North America, and the Perry Clan Representative of the Troy/Fall River Wampanoag, the true diversity of contemporary Natives in the Commonwealth was driven home. Our youth speaker at the last event again reminded us of the ongoing impacts of settler colonialism: a fracturing of what were once closely connected peoples — now islands in a sea of visitors — struggling to either maintain or re-establish relationships severed or made brittle due to differential political status or the simple, ongoing challenges of survival.

As with the first three sessions, this last one also included historical perspectives on the Troy/Fall River Wampanoag, the Massachusett, and both of their ongoing challenges for persistence in a society that is quite happy to assume they no longer exist.

Perhaps the most commonly seen, and voiceless, image of a Native is that on the state flag, gazing at the residents of the state with a sword poised over his head. That sword could be called many things, and has moved from being an actual sword used to decapitate Native Peoples in the 17th century, to a symbol of ongoing threat, distress, and erasure. As our youth representative at NAICOB reiterated, it is difficult to retain Native culture and identity when most things in contemporary Massachusetts call for its loss.

And so here we are.

We have heard directly from many Native communities in the Commonwealth and from a multiplicity of perspectives; youth, elders, and middle-aged. What they hold in common is that the social contract with the state is fractured at best, or non-existent at worst. Native land, and autonomy, was surrendered for peace, or forcibly extracted, yet the resulting protection by the shared government never happened. Instead, Native Peoples in Massachusetts continue to be marginalized in what is frequently viewed as post-racial America, and are almost invisible in one of the geographic areas that most prizes its diversity, yet won’t pursue Indian Education funds to benefit its Native youth. It is a dilemma, but one that may have some paths forward.

Whether we look at the international perspective of indigenous rights, greater alliance building locally, or both, there is something we as Native Peoples and our allies can do. We can better plan, better articulate, and organize to let people of good will know that the old agreements are still valid, and that they have not been kept. If America, and Massachusetts, is truly to move forward beyond its legacy of racism towards its indigenous Peoples, it must first listen and acknowledge, then reconcile.

For a social contract to be valid, both parties must be willing participants. Perhaps we can get there yet. Our next dialogue for forging a path forward will be held on May 11th from 11AM – 2PM at Suffolk University Law School and will be co-hosted by the Indigenous Peoples Rights Clinic and the Institute for New England Native American Studies. I hope you can join us! Please RSVP to nfriederichs@suffolk.edu by May 6th if you’d like to attend. Lunch will be served.

For their participation in this latest event, we would like to specifically thank the following representatives:

- Massachusett Tribe at Ponkapoag

- Nanouw’etea Ren Green, Medicine Sac’hem and Leader of Ceremonies;

- Faries (Strong Medicine) Gray, Sagamore

- North American Indian Center of Boston

- Joanne Dunn, Micmac, Executive Director

- Isabella Cisneros, Lower Coos, Siuslaw, and Umpqua

- Perry Clan of the Troy/Fall River Wampanoag

Thank you!