by Connor Capizzano’15

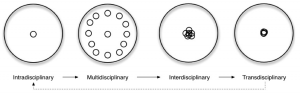

Scientists have historically worked within one field of academic study (discipline) to address specific research questions. However, environmental problems (e.g. conservation, sustainable resources, and climate change) are often too complex and dynamic to be evaluated with a single discipline (Evely et al., 2010). The abundance of commercially- and recreationally-important fish species (e.g. Atlantic cod), for instance, is a major concern due to the potential impact on the surrounding ecosystem and socio-economics of the region. In order to properly investigate such issues and their associated impacts, varying levels of investigation are required. Alexander Jensenius illustrates these degrees of disciplinarity in his online blog where he visually distinguishes between intradisciplinary, multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary (see below). Moreover, Evely et al. (2010) lends further information to explain the differences between them.

Intradisciplinary involves working within a single discipline to answer specific questions. Multidisciplinary is characterized by several different academic disciplines where research participants draw on their own disciplinary knowledge. Although there is no mixing of effort among the multiple disciplines involved, the general goal is to exchange knowledge and compare results. In contrast, interdisciplinary focusses on crossing subject boundaries of multiple disciplines in order to integrate and synthesize new knowledge and methodologies. Finally, transdisciplinary aims to remove these discipline boundaries and integrate research knowledge and methodologies (similarly to interdisciplinary). As described by Evely et al.(2010), transdisciplinary also attempts to assimilate non-academic (e.g. public) participants to answer research goals with newly obtained power.

At the University of Massachusetts Boston, graduate students (fellows) of the Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship (IGERT) are being taught the foundations of these disciplinarities and their importance in environmental research. The aptly named “Coasts and Communities” IGERT program at UMass Boston provides interdisciplinary perspectives and training for investigating the effect of prominent environmental issues (e.g. climate change, overfishing, pollution) on the Greater Boston area. This fellowship program aims to increase the knowledge base of its participants in order to mold us into a new generation of scientists. We are being trained to more easily integrate multiple disciplines and potentially “transcend” academic boundaries in order to solve research questions in these intricate ecosystems.

We, at UMass Boston’s IGERT program, were able to visit Nantucket this past September to be educated in this island’s diverse culture and environmental issues. Understanding the dynamic relationship between environment and socio-economics is vital to Nantucket’s thriving existence. As such, interdisciplinary research among varying federal, non-governmental, and academic institutions can possibly alleviate the current problems the island is facing. Adapting successful environmental management plans from elsewhere could allow Nantucketers to harvest its lucrative bay scallop for years to come. Designing renewable energy projects that do not inhibit Nantucket’s historical beauty or the marine ecosystem would be highly beneficial, especially in regards to its growing energy demand. Although we learned of the importance of such integrated approaches to Nantucket’s well-being, we further understood their application elsewhere in the region. It may only be our first semester at UMass Boston and with the Coasts and Communities IGERT program, but we are making great steps forward for addressing issues that affect all of us in Boston.One such complex and dynamic system is the Massachusetts island of Nantucket (25 miles south of Cape Cod’s town of Hyannis) that is world-renowned for its rich history and tourism industry. However, Nantucket and its residents are suffering the erosive power of the Atlantic Ocean, eroding the Siasconset bluff at an average rate of 3 to 4 feet per year with no sign of stopping in the near future. Nantucket maintains the last wild-caught scallop fishery in the United States that is critical to the island’s history, culture, and economy. Despite residential effort to keep this fishery sustainable, the scallop’s essential eelgrass habitat is threatened by increased nutrient levels from both land and water pollution.

Additionally, although separate from the mainland in many ways, Nantucket is dependent on the “continental United States” for stable fuel and electricity, especially during the peak summer tourism season. National Grid is currently supplying the island with electricity via two undersea cables and possibly planning on installing a third due Nantucket’s increasing demand. Although renewable, clean energy projects could instill Nantucket with greater independence (i.e. Cape Wind, the United States’ first offshore wind farm), such plans are often discouraged due to finances and preservation Nantucket’s historical district and landscape.

Stay tuned for our next IGERT post by Peter Boucher!

Reference:

Evely, A. C., Fazey, I., Lambin, X., Lambert, E., Allen, S., and Pinard, M. 2010. Defining and evaluating the impact of cross-disciplinary conservation research. Environmental Conservation, 37(4): 442-450.